Baseball Reference and Pitching

Using Baseball Reference to Enhance Pitching in Your Replay

Baseball Reference and Pitching

We talked about using Baseball Reference to do defensive lineup and batting order research last time. We also hinted at how to easily find real-life pitching rotations.

Of course, there’s more to pitching in baseball replays than just the rotation, as all replayers know. There are questions about how much rest individual starting pitchers need, how often individual relievers should be used, and how long they should stay in the game, among other things.

I’ll be blunt: Baseball Reference doesn’t have a magic button to instantly answer all of your questions about relief pitcher usage. However, if you learn how to use it well, you can find some guidance on how to realistically manage your pitching staff.

Rest

The most obvious question is how often we can throw our pitchers in the mix. How much rest did these guys get in real life, and who could we theoretically put out there every day?

You’ve got two options to determine this. You could look at the pitching staff as a whole to get a general idea, or you could look at individual players to determine individual roles.

Rest: Team Approach

Let’s look at the team first. Once again, we’re going to use the 1949 Brooklyn Dodgers as our example.

When we scroll down on the 1949 Brooklyn Dodgers page, we eventually come to this section:

Your first instinct will probably be to click on “Game Logs” under “Pitching.” That brings us the “Team Pitching Gamelog,” which looks something like this:

Now, this isn’t bad — but it also isn’t necesarily all that useful. I suppose this could be helpful if your plan is to use the exact same pitchers in every game for the same number of innings that they pitched in real life. Most of us aren’t interested in that level of strictness, however — and you’re going to spend a long time with your spreadsheet if you want to convert this chart into something that tells you about days of rest.

Let’s go back to that team page above. Instead of looking at the logs, let’s click on “Detailed Stats” under “Pitching.”

There is an almost overwhelming amount of information on this page. What we are generally interested in is a bit further down. Click on “Team Starting Pitching” next.

Some of these columns will be instantly recognizable for you, and some will seem a bit odd. What I find most useful here as a replayer is “sDR” and “lDR,” which stand for “short days rest” and “long days rest” respectively.

“Short days rest” refers to pitchers starting with less than 4 days of rest — something that is a lot less common today than it was in 1949. And “long days rest” refers to pitchers starting with more than 4 days of rest.

When we sort by “sDR” (easy to do — just click on the red “sDR” on the top), we see immediately that Don Newcombe was the Dodgers’ workhorse:

In contrast, Preacher Roe was the leader in starts with more than 4 days of rest — a bit of trivia that you probably never knew or thought of.

Note that this won’t tell you exactly how to set up Brooklyn’s rotation. It will, however, give you a ballpark idea of which pitchers pitched on short rest and which pitchers need an extra day or two.

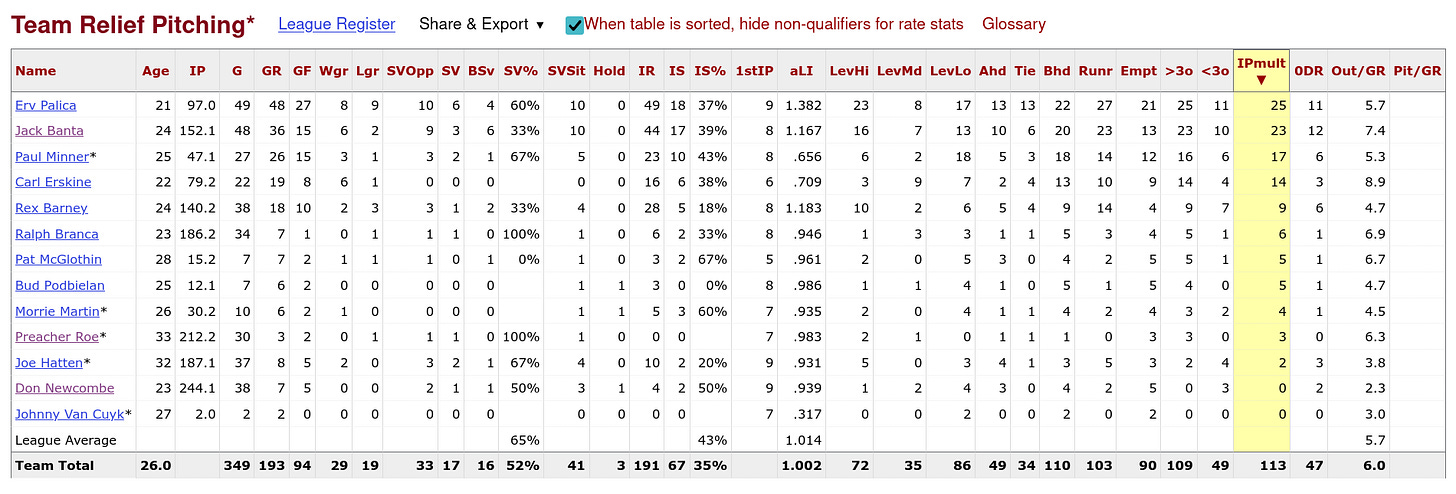

What about the relievers? Well, Team Relief Pitching just so happens to be right below Team Starting Pitching:

I skipped a step here, as you can see. I’ve already sorted these relievers by “0DR,” which stands for appearances with 0 days of rest. As you can see, this wasn’t exactly uncommon back in 1949.

We can also use this spreadsheet to get a quick idea of which relief pitchers tended to pitch for more than one inning. Let’s say you’ve found yourself going to the bullpen in the 5th inning after your starter was shelled off the mound, and you need somebody to eat up some innings. You want a pitcher good enough to stay in there — and you also want to be realistic.

If you sort by “IPmult” (games in which the reliever pitched more than 1 inning), you’ll see which Dodger relievers tended to stay in a bit longer:

Finally, let’s say you’re interested in doing a bit of historical baseball research alongside your replay. You’re curious about the impact that short rest had on pitcher performance during the 1949 Brooklyn Dodger season.

If we go back to the team page and click on “Pitching Splits,” we’ll come up with this:

This is one of those pages where we can break a season down in all sorts of possible categories. We’re interested in Days of Rest:

You can see quite a bit of information here just at a glance. For example, 4 days of rest seems to be the sweet spot for Brooklyn starters. Those with 3 days of rest gave up slightly more runs, hits, and walks, and those piching with 5 days of rest also performed slightly worse.

If you click on any of the listings in red on the left, you can get more detail. For example, we can see more detail about the pitchers who started with only 1 day of rest:

Unsurprisingly, Don Newcombe had 3 of those 5 starts.

Rest: Individual Approach

Speaking of Don Newcombe, we can learn more about his 1949 season by visiting his individual page.

We’re interested in his 1949 performance — specifically how many days he rested between starts. The best place to find this is under his game logs. Hover your mouse above Game Logs and click on “1949” under “Pitching:”

That brings up this page:

We can see immediately what kind of rest Newcombe had as a pitcher in 1949. Note that the “Days of Rest” listing includes both starting and relief performances — and, yes, Newcombe did come in as a reliever the day after starting twice in 1949.

If you’re really interested in the details, you can find them by scrolling down just a little:

Usage

Now, remember that real life usage does not have to dictate how you play your replay. You don’t need to put Newcombe in for 3 innings the day after he threw a complete game, for example. You can play your game the way you want.

What this approach can do, however, is give you some context to the general statistics you see in any given season. It turns out, for example, that Brooklyn Dodgers pitchers starting games with 1 day of rest in 1949 tended to pitch well because they tended to be Don Newcombe, a pitcher who pitched extremely well in all appearances that year. With a little bit of practice, it’s easy to dig down and figure out where outliers and unusual events exist.

My recommendation for using this is to look at the team you are replaying in general at first. Once you have an idea of general usage and pitching rotations, you should then look at a few individual players to understand general roles and usage. You could look at every pitcher one-by-one, but I find it important to have the general context in mind before you look at each specific case.