Bill James on the Doubledays Buying The Mets

I’m probably not winning any bonus SEO points with that headline, but I don’t know of any better way to put this.

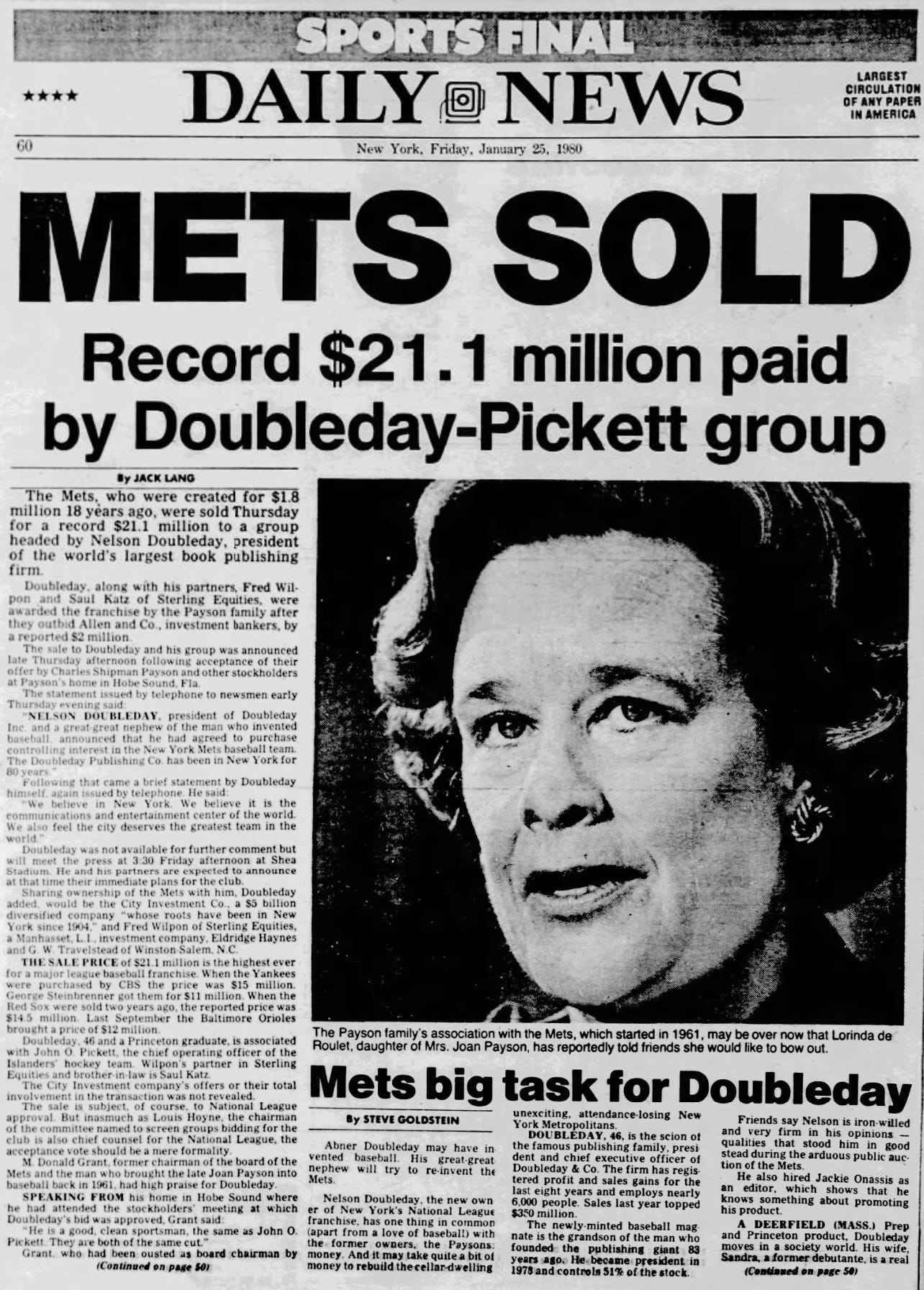

Back in January 1980, the Payson family sold the New York Mets to the Doubleday publishing company.

The price? $21.1 million.

And, as you can see here, this was a record price for a Major League Baseball team. It also represented a great profit from the measly $1.8 million that the Mets cost when they were created in 1962:

As most of you probably already know, this sale couldn’t have come too soon. After finishing in third place at 86-76 in 1976, the Mets went straight down to the cellar, finishing in last place for three straight seasons.

The nosedive coincided with the trade of Tom Seaver in 1977. In fact, I think you could probably argue that the bottoming out was largely caused by that Seaver trade. Fan interest dwindled, and the team was going nowhere fast.

Reflecting on all of this, Bill James wrote the following for Esquire:

Now — was James right?

Well, we know that the “five years to recover” timeline was wrong. The Mets wound up with a superb farm system, and were in contention as early as 1984. Between 1985 and 1990, the Mets were arguably the most consistent team in the National League — though they only had a single World Series appearance to show for it.

And, interestingly enough, it seems that the Mets did spend their way to victory. Well, that is, they tried to — at first, anyhow.

Way back in 2004, Doug Pappas wrote this fantastic piece for Baseball Prospectus on marginal payroll per marginal win.

The idea behind it is pretty simple. You compare the payroll of the team to its performance on the field. His inelegantly named “Marginal $ / Marginal Win” formula tells you how much money above the minimum (i.e. paying the minimum salary to every member of the 25 man roster) a team paid for every win above the minimal expectation (playing .300 ball).

I’m not doing a great job of explaining this, of course. You can read Pappas’ excellent explanation here.

So, for example, on August 31, 1977, the New York Mets had a payroll of a whopping $1,469,800 — next to last in the National League (the Astros paid only $1,399,325). The 64-98 Mets wound up paying $60,896 per marginal win. Sure, they didn’t have a huge payroll, but they still wound up paying more money per win than the average National League club in 1977 — largely because they won so few games.

Check out the M$/MW numbers Pappas calculated for the Mets from 1980 to 1984:

1980: $146,830 — second in the National League (the awful Cubs were paying $236,744 per marginal win to finish 64-98)

1981: $297,536 — first in all of MLB (all this for a team that played .398 and missed the expanded playoffs)

1982: $392,750 — first in all of MLB (they finished 65-97)

1983: $619,156 — first in MLB by a large margin (they finished 68-94)

1984: $164,315 — last in the National League, and one of the lowest totals in all of baseball (they went 90-72)

Now, there are some pretty obvious problems with the Pappas approach. It doesn’t take into account the inflation of salaries over this era, for example. Teams that won more games could offset their high payroll costs, which means that the Mets largely had the highest M$/MW total in all of baseball because they couldn’t win.

But this approach is also a pretty simple way of telling you what actually happened. The Mets decided not to jump after every big name free agent, and instead focused on developing good young talent. And that’s where they had success.

As exciting as that Juan Soto signing in December might have been, you need to keep in mind that splashing big for free agents usually doesn’t work. The best approach in the era of free agency is still the approach that worked best before free agency: developing good young talent.