Book Review: Baseball Dynasties: The Greatest Teams of All Time

Another Look at a Classic

This post includes affiliate links. If you use these links to purchase something, this blog may earn a commission. Thank you.

The Greatest Teams of All Time

Review of Baseball Dynasties: The Greatest Teams of All Time

There’s a strange magnetic connection between baseball replayers and the greatest team of all time discussion. I’m not certain that I fully understand the attraction. For some reason, those of us who like to replay old seasons and learn first hand about the more obscure parts of the history of the game also are attracted to the old discussion of which team was the greatest of all time.

This Neyer - Epstein book is not the final say in which teams are the greatest of all time. However, it is a good jumping off point.

Ratings

Most of you have probably read this book already. If you haven’t, I’ll give you a really brief rundown of the idea.

The basic rating idea here is pretty simple. Neyer and Epstein have come up with a statistic that they call an “SD score.” This is simply a combined measure of the number of standard deviations a baseball team’s runs scored and runs allowed are from the league average.

Standard deviation is a little bit complex, but I bet you can figure it out if you take a few minutes to think about it. It’s a measurement of how widely numbers within a group are spread. The basic introduction in this book is simple enough:

Neyer and Epstein take every single team in baseball history, calculate how many standard deviations its runs scored and runs allowed are from the average for their league, and look to see what the statistics come up with. This allows them to come up with a very quick rating of which teams could be considered the best teams of all time.

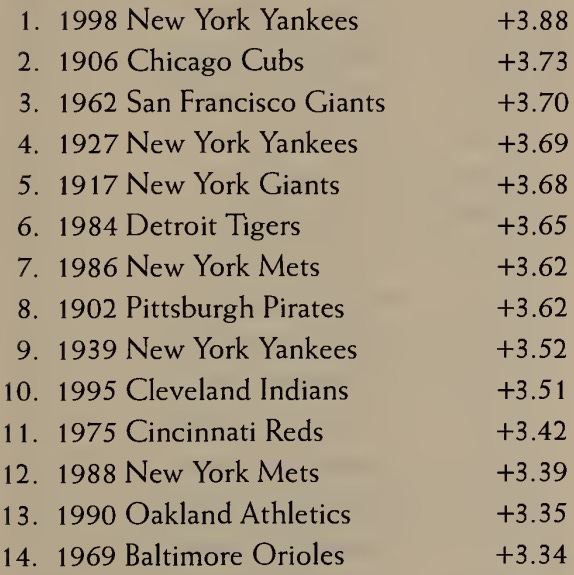

Most of the teams that rank the best are the teams you’d naturally think of, though there are a few exceptions. For example, here is their list of the top 14 single season “SD scores” in baseball history:

Similary, they calculate the top SD scores over time, in search of the mythical “dynasty.” Here’s a look at the teams with the top 5-year “SD scores” of all time:

This list seems odd for multiple reasons, of course. Why separate entries for the 1934 through 1943 New York Yankees, for example? Did the 1935 Yankees really have as much in common with the 1939 Yankees as the 1969 Orioles had in common with the 1973 Orioles?

Anyway, there is a lot to say about the “SD score,” including its strengths and weaknesses. I don’t want this to turn into a statistical discussion, though, and will save most of my comments for a future post. I do want to note here, though, that “SD score” is a horrible name for such a useful metric; I’ve got a different name for it that we’ll talk about in a few days.

Other Stuff

Now, if this book were just about the “SD score” concept, it would be pretty short. In the classic Bill James style, there’s all sorts of other stuff in here.

I found some of the other stuff good, though I was frustrated with how random its insertion seemed to be. For example, this graph shows up in the middle of a discussion about the 1906 Cubs’ double play combination (Tinker, Evers, and Chance):

I mean, this is great information, but it’s stuck in a random place for reasons that are not clear to me. And there’s no context here, of course. Whose attendance figures are we using? Do they realize that even hometown newspapers often offered differing attendance figures for the same games?

Replayers will likely be interested in sections on how each of the great clubs were built. For example, here is the section on the construction of the 1912 New York Giants:

Then again, that’s all there is to that section — just a little anecdote, maybe 4 paragraphs or so, and not really a deep dive. One wonders how it would have been if Neyer and Epstein had actually dug into the rosters looking for gems.

What I Disliked

I like the methodology here, and I like some of the extra articles… sometimes. However, it quickly becomes clear that there’s a lot of filler.

Some of the sections on each team feel like complete throwaways, with very little information. The section on “the ballpark,” for example, seems to completely ignore the work of other contemporary students of baseball on park factors. Take, for example, their section on the home park of the 1929 Philadelphia Athletics:

There’s no acknowledgement here of the fact that “power hitting” refers to more than just home run hitting, no close look at what might have changed in the ballpark to cause run scoring to change over time, and very little actual analysis here. They even missed the story about the riot that accompanied the demolishing of Connie Mack Stadium in 1970; even I know about that (and I was born over a decade later).

Similarly, the player analysis borders on sabermetric ideas without really embracing them. Neyer and Epstein use something called “Real Offensive Value” (ROV) and “Offensive Winning Percentage” (OW%) when displaying common lineups, resulting in sections like this one for the 1927 Yankees:

I understand that “OW%” is supposed to tell you what the winning percentage for a team would be if every offensive player were the player in question, though I really struggle to understand what that tells me about Miller Huggins’ lineup selection. “ROV” seems to be yet another attempt to take the components that make up the offensive side of WAR and express them in the more familiar batting average scale. Again, speaking as a replayer, I’m just not certain that I understand what this is supposed to tell me, or why it’s interesting.

Neyer and Epstein weren’t able to benefit from Retrosheet’s reach into the past, of course, or Baseball Reference’s amazing ability to give us lineup analysis at a glance. If they decide to update the companion website for the first time in two decades, they might want to put in a section explaining that the 8 players in their “regular lineup” only appeared in that order 25 times in 1927:

It would have been much more interesting to look closely at game-by-game accounts to understand how lineup rotation worked. Here are the 1927 Yankees’ lineups through the second game on May 27, for example:

Again, I know that they couldn’t get this information as easily when this book was written in late 1999. However, you do wonder how hard it would have been to open up a newspaper or two and do some actual primary source research. I guarantee that even the most ardent baseball historian doesn’t immediately know that the 1927 Yankees rotated Grabowski and Collins on a game-by-game basis early in the season.

The Worst Part

I liked this book, I really did. In fact, I’m going to talk about it a lot. However, it’s hard for me to analyze it without talking about its weaknesses.

The worst part of this book is clearly Chapter 20, which is where Neyer and Epstein are supposed to come to a conclusion. Rather than writing an analysis and a quick conclusion, they write in a conversational style that reads like a cross between a sitcom script and a really frustrating message board conversation:

I mean, the discussion here isn’t awful. They are correct that “SD scores” over 3.00 in a single season is incredible. And that makes sense when you understand how standard deviation works given a normal distribution. An SD score that combines to be over 3 standard deviations from the mean is so unlikely for a “normal” team as to be laughable. It’s a clear sign that you are dealing with a team that was simply out of its league.

But why is Rob asking Eddie to refresh our memories, and to expand on his thinking? I mean, is this a transcript of a sports talk radio show? Who writes like this?

Discussion Starter

In the final analysis, this book is an excellent discussion starter.

It’s worth a read. However, it is frustrating if you want to replay a season with these teams. You’re not going to learn as much as you should about how the teams were constructed, how the lineups worked, what transactions took place, or anything like that.

The “SD score” concept is a good one, though, even though it seems to have been ignored by the major statistic compilation websites. Personally, I consider it to be more useful from a replay perspective than WAR.

We’re going to use concepts and ideas from this book in future posts. My hope is that we can expand and improve on some of the ideas that were originally introduced here. The plan is to take the “SD score” concept out of obscurity and examine it a little bit closer, as well as to give the teams in question a much more thorough examination.

After all, if you want to start pitting these teams against each other in some mythical “greatest team of all time” project, you’re going to need to understand how the teams actually worked.