Bunt Disasters With The Pitcher

One of my games sparked this post.

Neither the Phillies or Reds are going to do anything spectacular in my 1908 replay. They’re both bottom dwelling teams in the National League — patsies destined to be taken advantage of by the Giants, Cubs, and Pirates.

Nobody thinks fondly of the 1908 Phillies or 1908 Reds, of course. You don’t start this kind of replay with fond dreams of playing a ton of games with either one of these teams. These are the sort of games you tend to roll through quickly, hoping to get on to the good stuff.

Even the boxscore of this one seems pretty humdrum:

There were only 2 successful bunts all game long — both belonging to Reds shortstop Rudy Hulswitt.

But what you don’t see here are all the unsuccessful bunts by both George McQuillan and Bob Ewing.

And I think the problem lies with the old APBA boards.

A Sacrifice Oddity?

The original 1951 version of the APBA baseball board game came with a separate booklet for sacrifice plays. I’m sure of that thanks to this APBA Blog post, as well as this Delphi Forums discussion.

In the 1953 version, a hit and run play was added to the sacrifice booklet. Of course, the 1951 and 1952 editions of APBA’s baseball game are so rare that it’s hard to find any photo copies of versions with only the sacrifice play.

The earliest version I could find comes from 1952, courtesy of a reader of this blog:

There’s something specific here I want to show you.

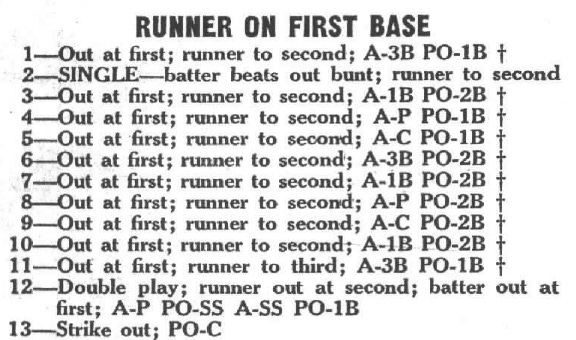

Look at play result #13 with a runner on first base:

It’s an ordinary strikeout, right? Nothing happens to the runner.

Now look at the same result with a runner on third base:

The runner is put out at home. My guess is that he should be given a caught stealing, since the batter did not put the ball in play.

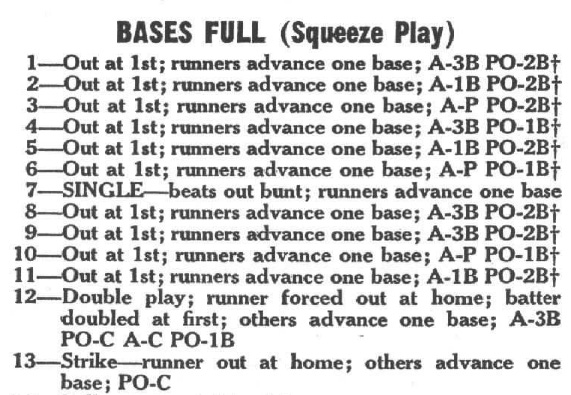

It’s not only the runner on third base variety that has this oddity. Look at what happens in the following situations:

The punishment for rolling play result #13 only exists with a runner on third base. In all other base runner situations, the result is simply a sacrifice, with no attempt at advancing.

It sort of makes sense. The runner was likely darting for home when the squeeze sign was given. He’s clearly a dead duck if the batter can’t make contact, right?

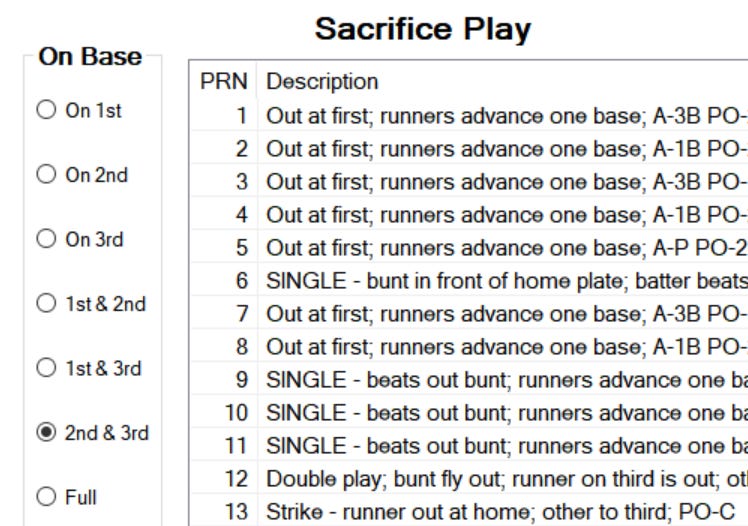

That’s almost certainly why the same results exist in NPIII:

The play is exactly the same. In fact, NPIII continues with the tradition of having the runner thrown out on a sacrifice resulting in play result #13 only if that runner is on third base.

The Problem

So what’s the big deal?

The big deal is that pitchers tend to have a lot of those #13 results.

Check out George McQuillan’s 1908 card, for example:

George has result #13 on 7 of his 36 dice rolls. You’ve got a 19.4% chance of him rolling a 13 in any given situation.

Now check out Bob Ewing’s card:

Ewing has result #13 on 7 of his 36 dice rolls — another 19.4% chance of him screwing up.

Now, if you had the pitcher come up with a runner on third base and less than two men out in 1908, what would you do?

You’d bunt.

Of course you’d bunt.

There’s no reason for you not to bunt. Neither of these guys were good hitters, even by 1908 standards. And there was a lot of bunting going on in 1908.

The result, however, is that you are punished for bunting. In fact, you’re better off letting these guys swing away. The chances of the runner being thrown out at the plate if you let them swing away actually diminish.

Is this system accurate? Or is this a major weakness in the APBA / NPIII system?

Absolutely. I checked my old APBA booklet and if the bunter rolls a 13 someone is out about a fifth of the time. It’s better to swing away and maybe the batter will get lucky or an error could pop up. It is too many outs. Those 13s will kill you. A problem with the boards. This is dead ball; you have to bunt.