Blog Legend

Blog Legend, you ask? Why is Cass Michaels a blog legend?

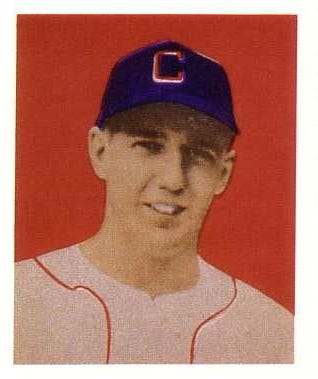

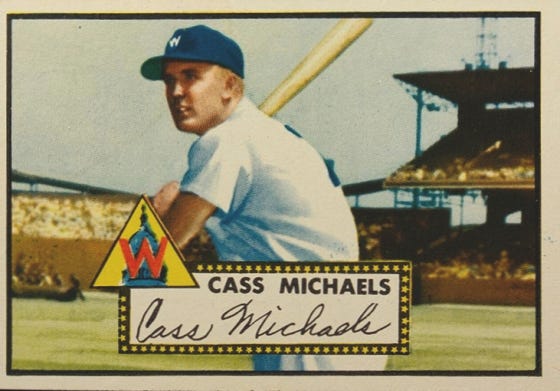

Well, he might not be the best player in the American League, but he certainly surprised me in this game. It’s still early in the 1949 season, I know, but I had absolutely no idea who this guy was before my replay started. I figured it would be only fair to try to learn all that I can about him.

Casimir Kwietniewski

Sadly, we don’t have a SABR Bio for Michaels at the moment. There is a BR Bullpen page devoted to him that contains some information, however, as well as a much more lengthy Wikipedia entry devoted to him.

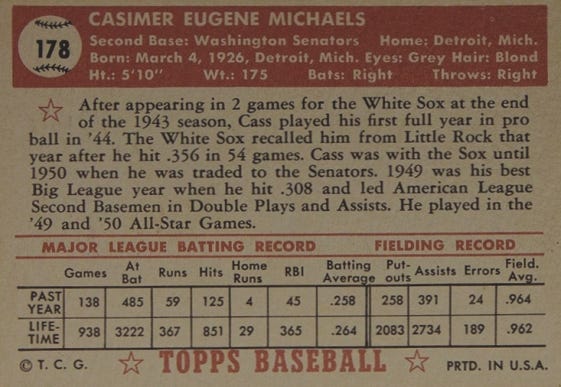

Cass Michaels was born Casimir Kwietniewski on March 4, 1926, in Detroit, Michigan.

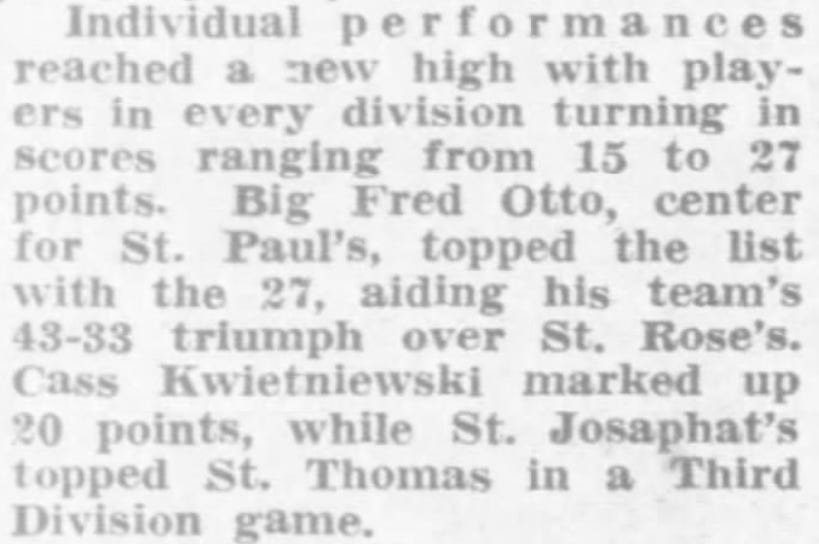

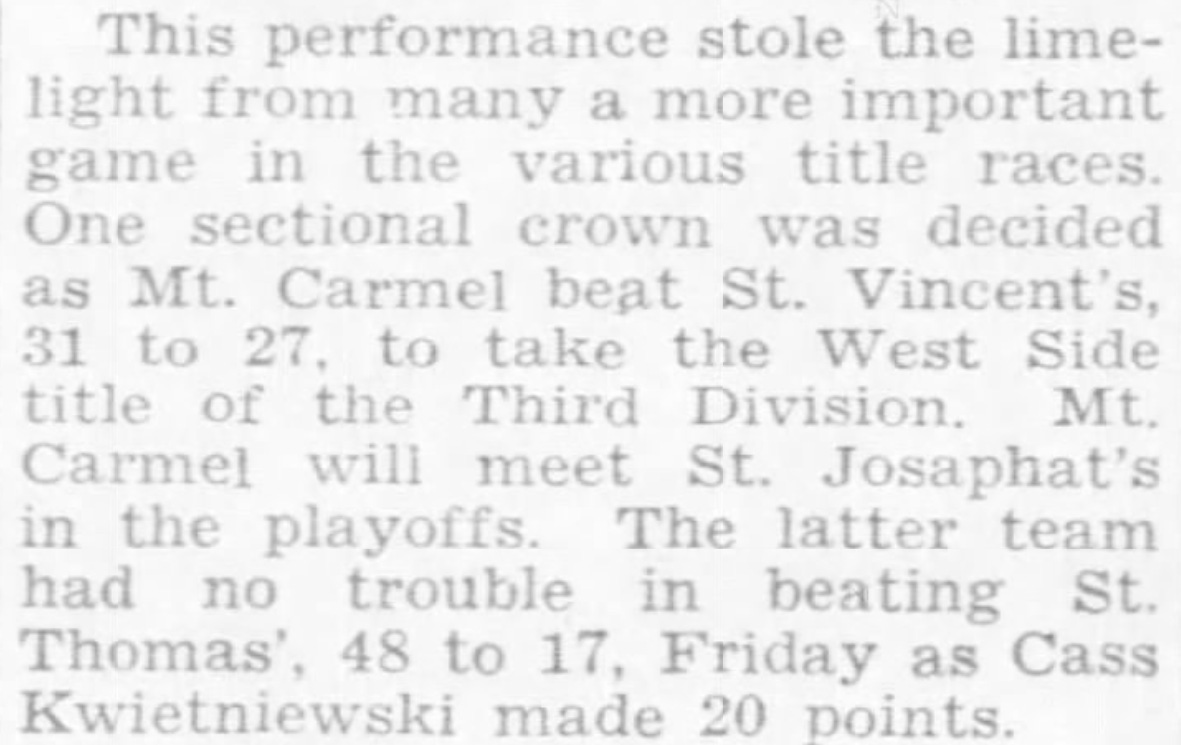

As is the case with so many future major league players, Kwietniewski was a great high school athlete. It seems that he played basketball for St. Josaphat’s, based on the following high school basketball clippings:

I’m not sure how to reconcile that with online reports that he attended Hamtramck High School.

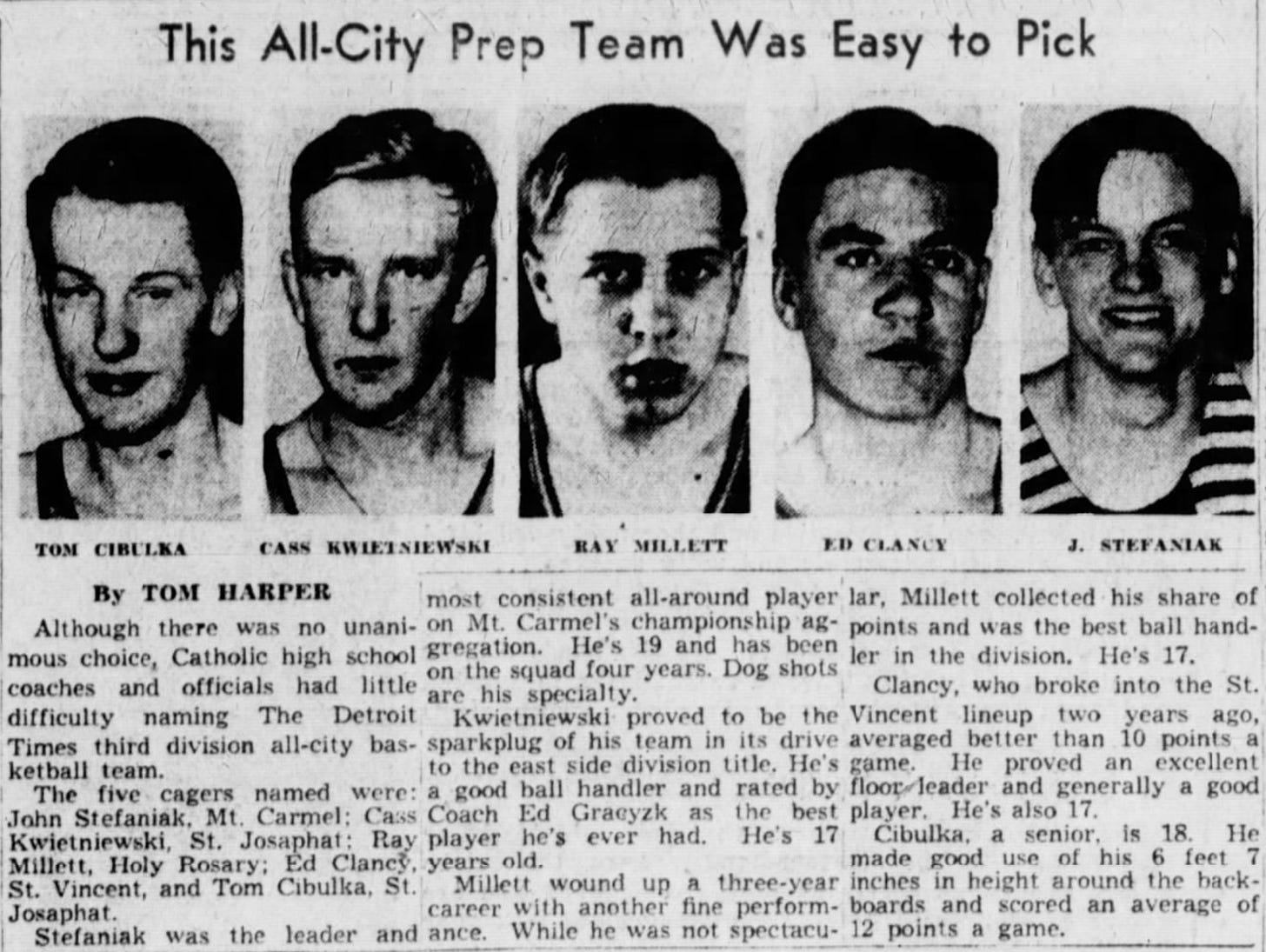

Kwietniewski even made the all-city prep basketball team that same year:

Big Leagues

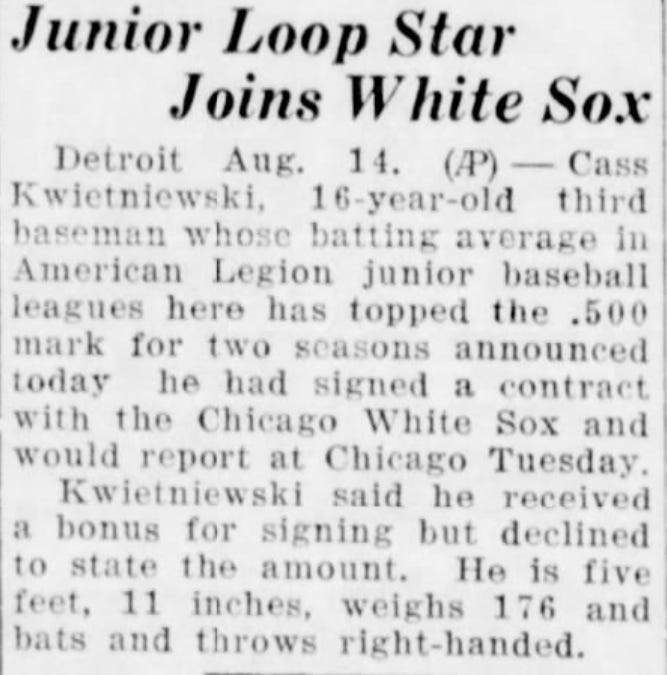

It didn’t take long for Kwietniewski to be discovered by major league scouts:

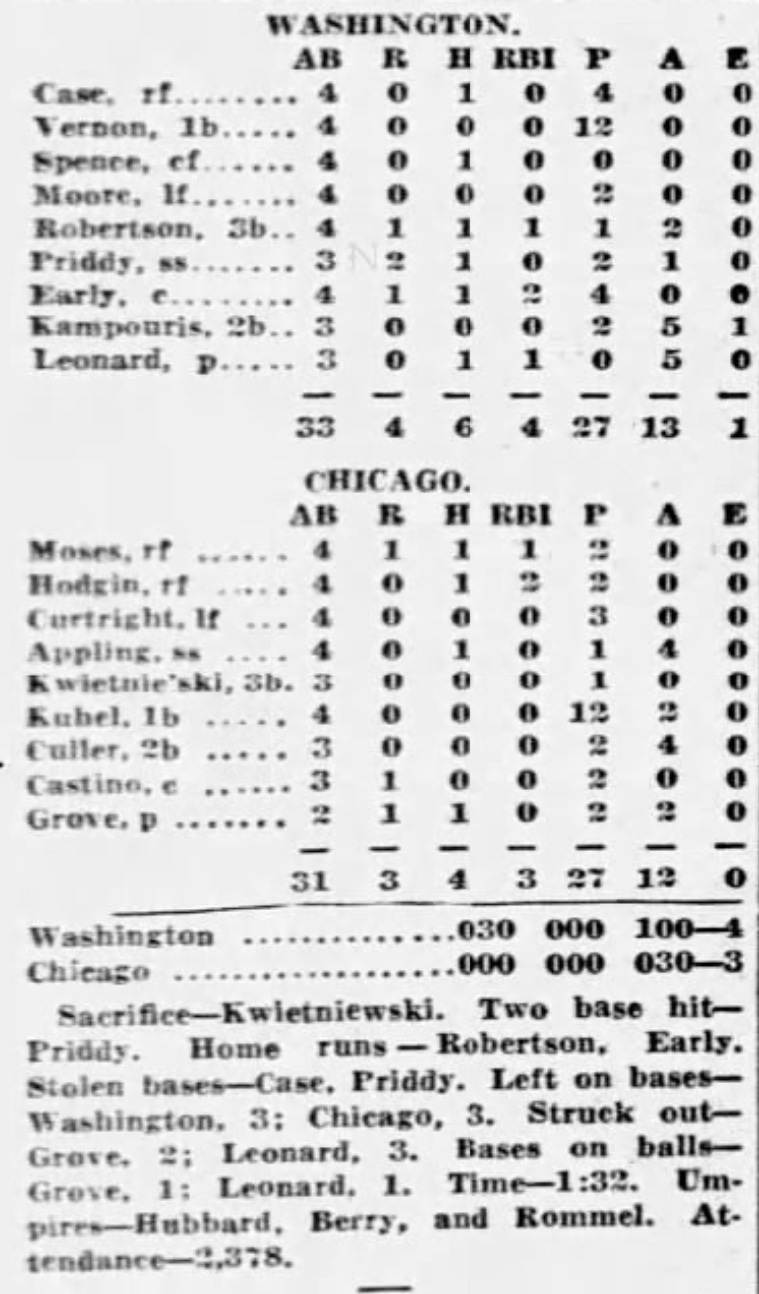

Now, Kwietniewski was the sort of name that didn’t quite fit into a standard boxscore, as you can see in this example from his very first Major League game:

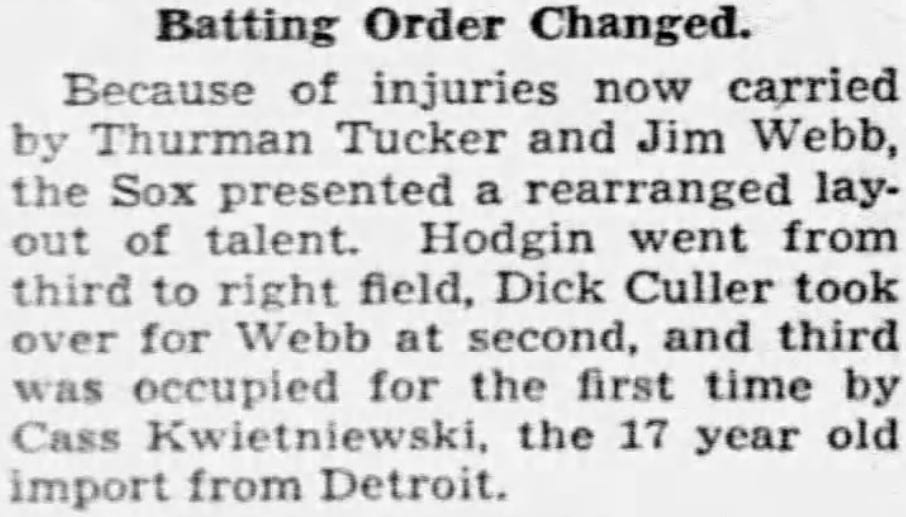

That’s right — Michaels started at third base in his very first big league appearance, playing the entire game. And this happened less than one week after his sudden signing was reported in papers around the country through the Associated Press.

He barely even received a mention in the official game report, receiving only a brief line in a paragraph near the end:

He started again the next day, and that was it for him in 1943.

At 17 years old, he was even able to get his picture in the Chicago Tribune during his brief stint with the White Sox that year:

Michaels was the second youngest player in the major leagues at the time, behind 16-year-old Carl Scheib, who we met just the other day.

Minors

I can’t find any evidence of Michaels playing in the minor leagues at all in 1943. It appears that he stayed with the White Sox for the rest of the season, though he didn’t have any more apperances than those two in August.

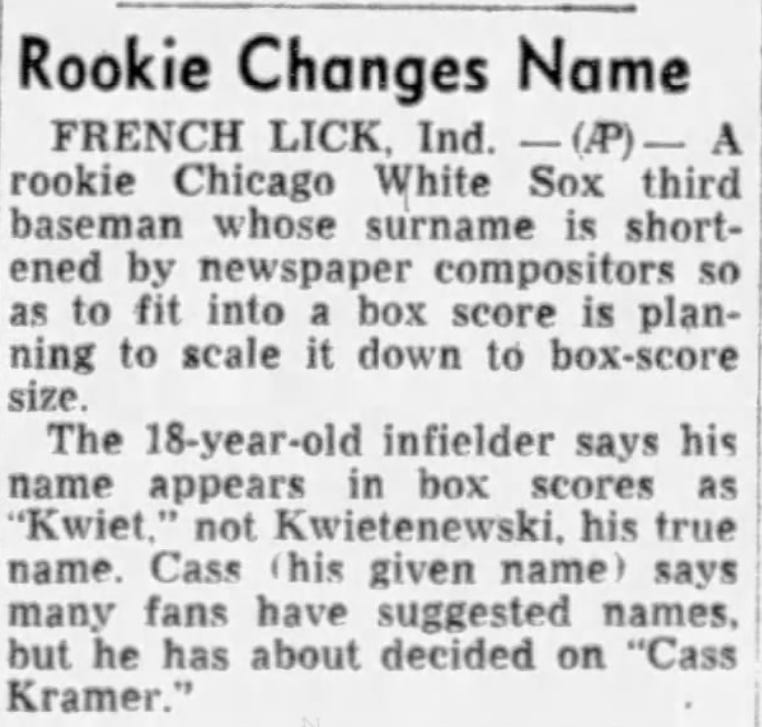

Before the 1944 season, Kwietniewski made a name change that received pretty wide press attention:

This report appeared in papers around the country, which I think is pretty impressive for an 18-year-old who had yet to show he could come close to competing at the big league level.

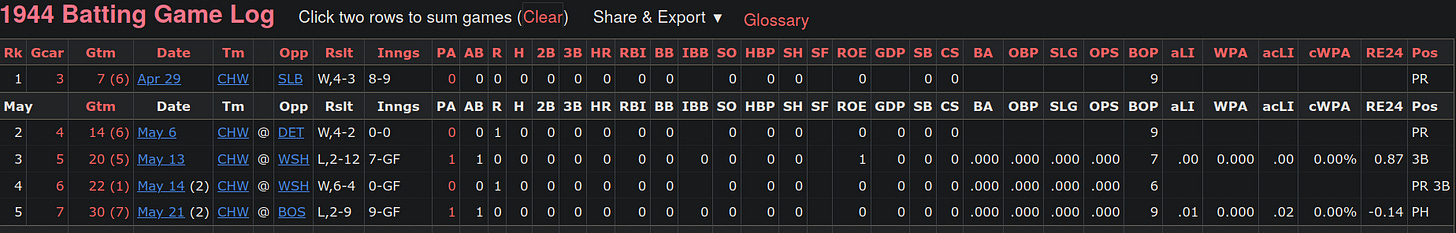

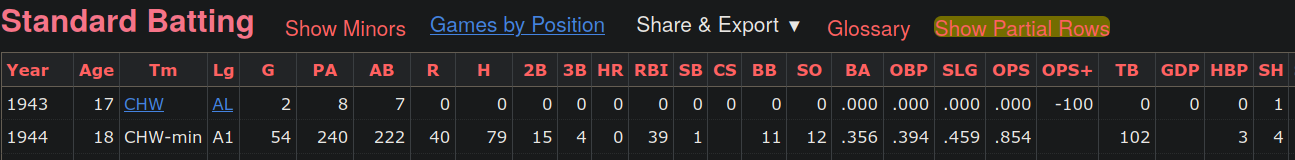

Michaels played briefly (and poorly) for the White Sox in early 1944 before being sent to Little Rock:

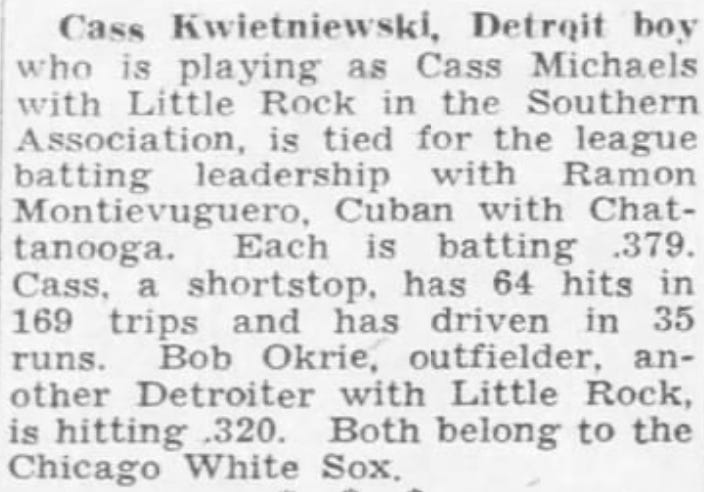

This, by the way, is a good example of where his Wikipedia biography is misleading. Michaels started the season initially with the White Sox before being sent down, but came back up to the big club after he did this to Southern Association pitching:

Hitting .356 with a little bit of power and a .854 OPS is a good way to get back to the majors, even at the tender age of 18.

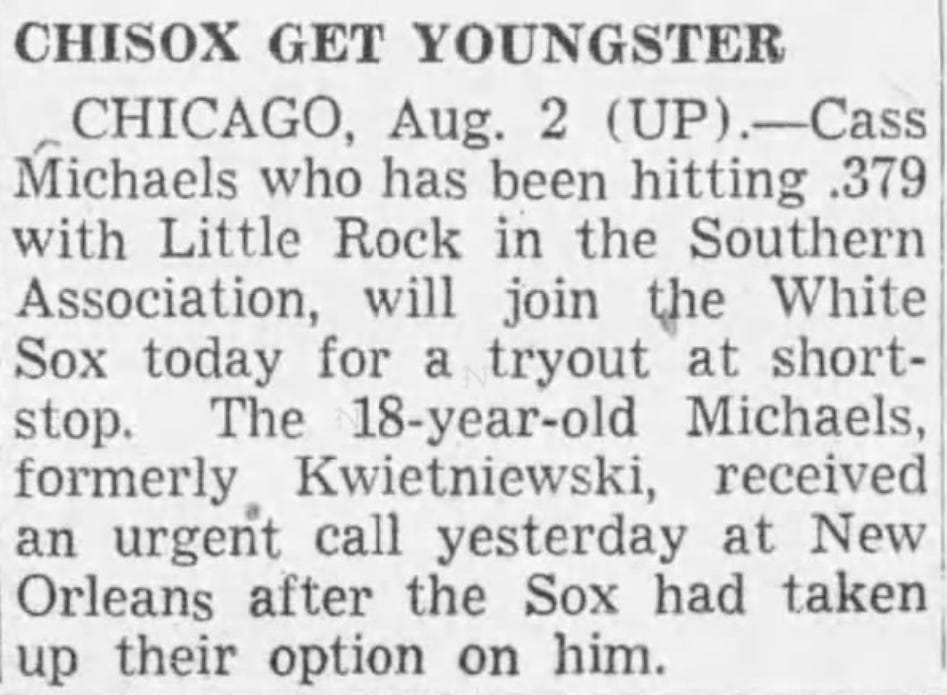

By this time, Kwietenewski seems to have changed his name to Cass Michaels for good:

In early August, 1944, Michaels found himself back up with the White Sox for good:

Though his .176/.200/.265 line in 1944 indicated that he was probably still too young for the big league club, Michaels stayed up for good this time, and never played in the minor leagues again. It’s kind of hard to believe today, but he only played 54 minor league games in his entire career.

1949

1949 marked Michaels’ breakout year. At the tender age of 23, he played quite well, managing a .308/.417/.421 line with 6 home runs, playing in all 154 games at second base for the White Sox.

He also earned a spot on the American League All Star team.

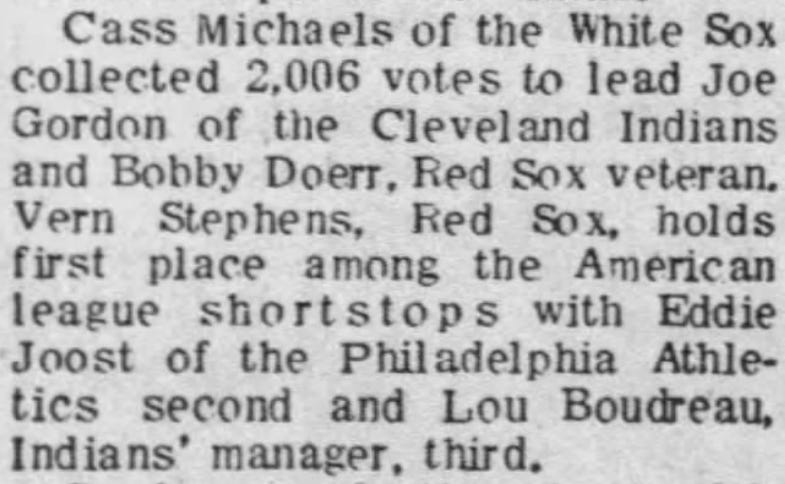

You can trace the voting for the All Star Game rosters in the old newspapers if you wish. I’ll give you a quick sampling here:

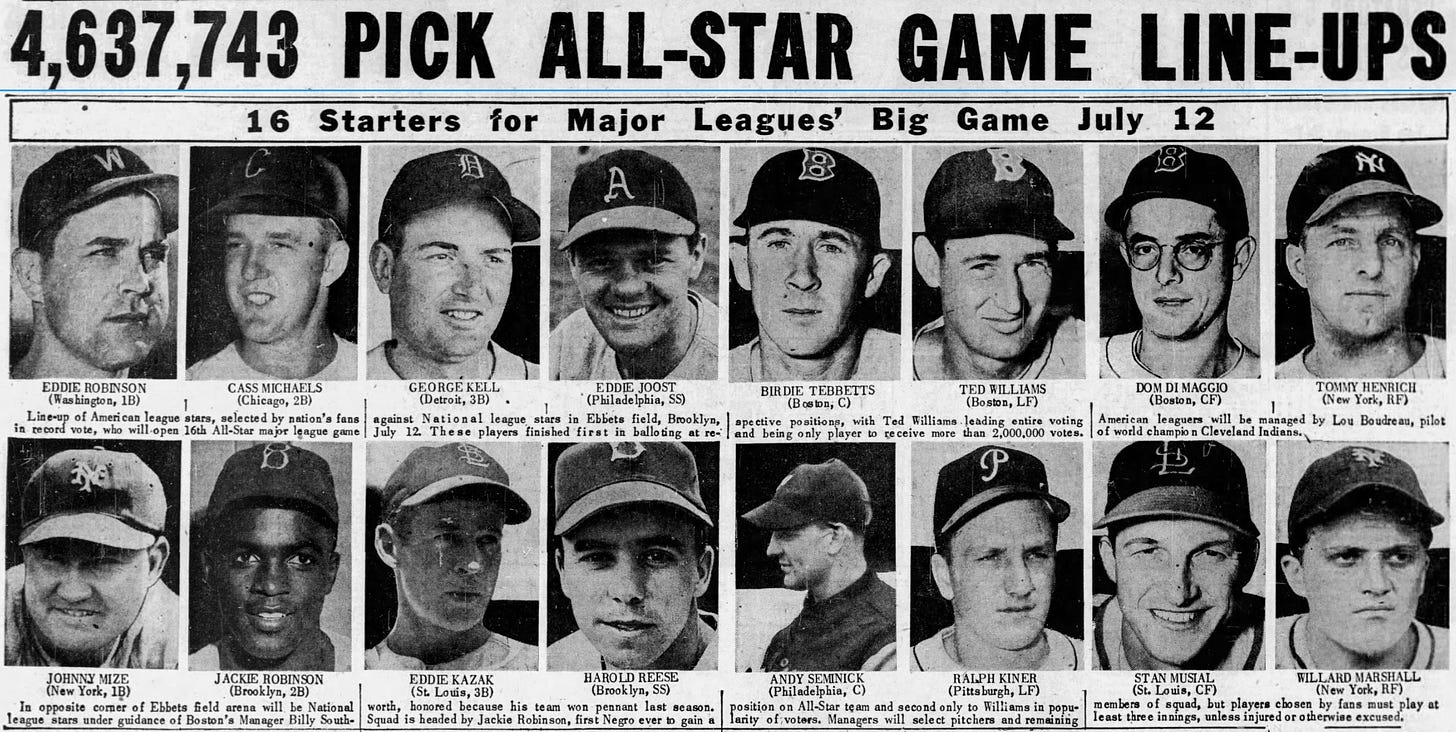

Here he is with his picture in the paper alongside the other successful stars:

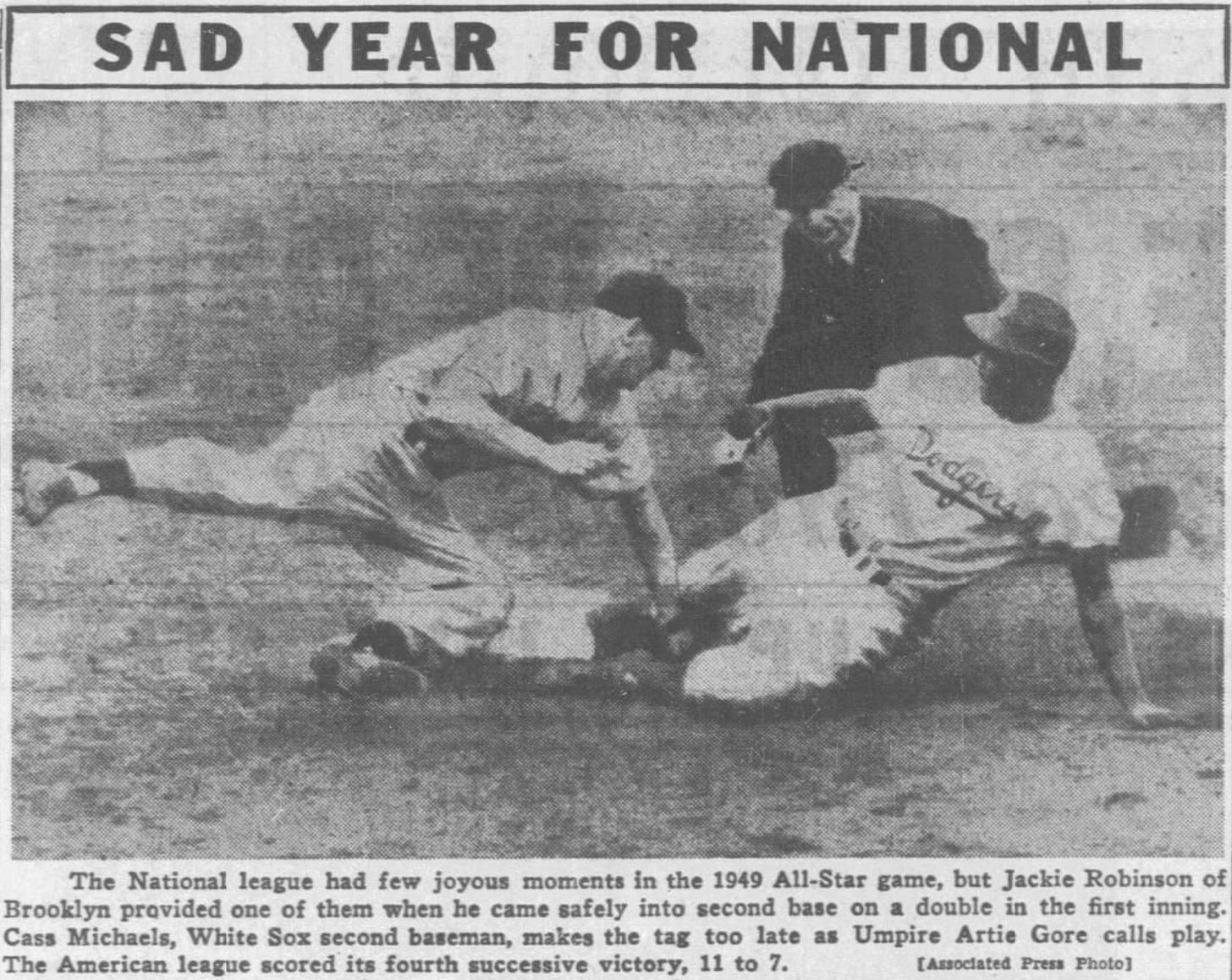

And here he is in action at the game:

The White Sox weren’t exactly great in 1949, as we’ve seen so far, but Michaels provided one of the few bright spots on an otherwise grim roster.

Trade

The good times in Chicago didn’t last long.

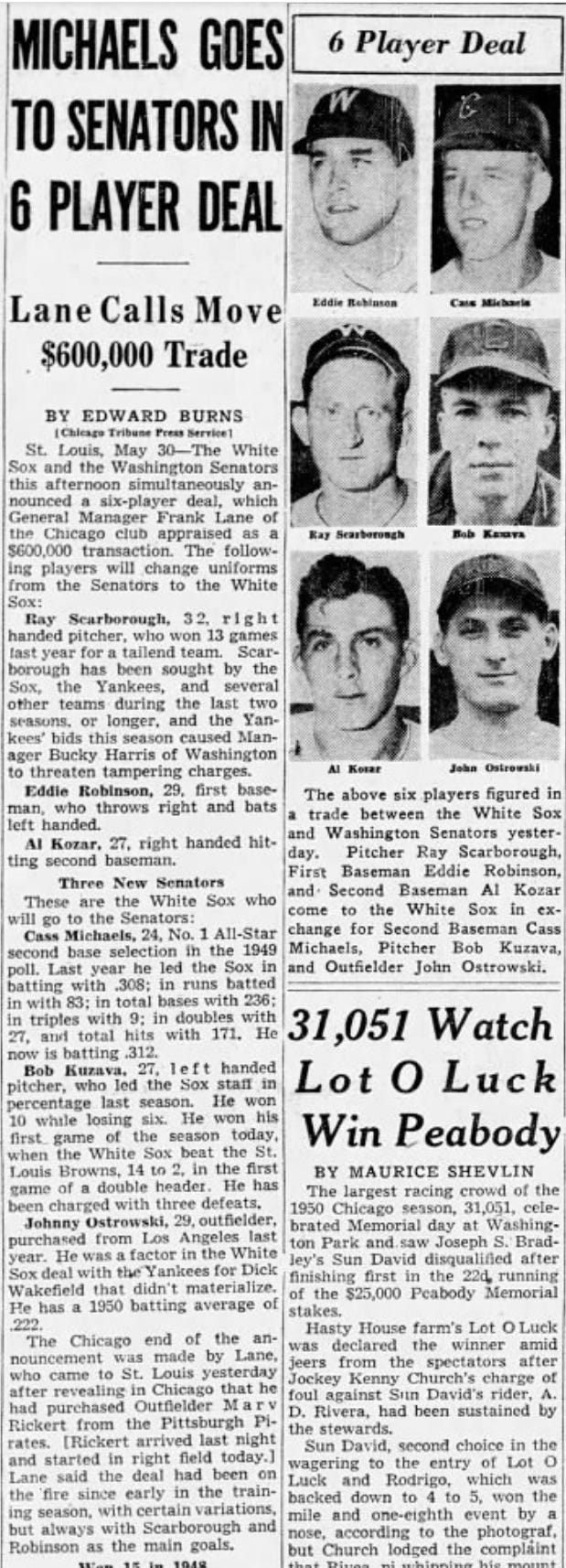

Despite hitting .312 for the White Sox in early 1950, Michaels soon found himself traded to the hapless Washington Senators:

The goal here seemed to be to get Eddie Robinson and Ray Scarborough. Robinson hit well during his time with the White Sox, earning All Star Game appearances in 1951 and 1952 before winding up with the Philadelphia Athletics in 1953. Scarborough, meanwhile, pitched poorly for the Athletics, and found himself with the Red Sox in 1952.

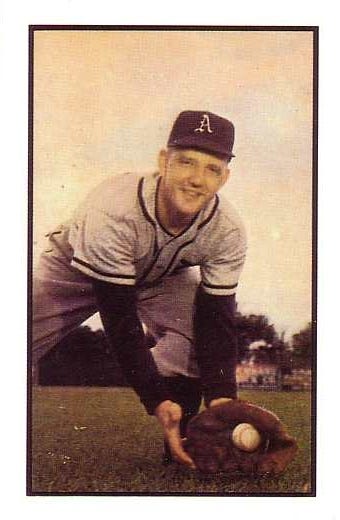

As for Michaels? Well, his hitting went downhill with Washington. He found himself traded to the St. Louis Browns part way through the 1952 season, and then to the Philadelphia Athletics for the rest of 1952 and all of 1953.

White Sox Again

Michaels found himself back with the White Sox in 1954, after the 1953 Athletics had an awful season.

He was 28 years old and nearing his prime. He played well in a starting role at third base, putting up a respectible .262/.392/.397 line with 7 home runs in 345 plate appearances.

But then disaster struck.

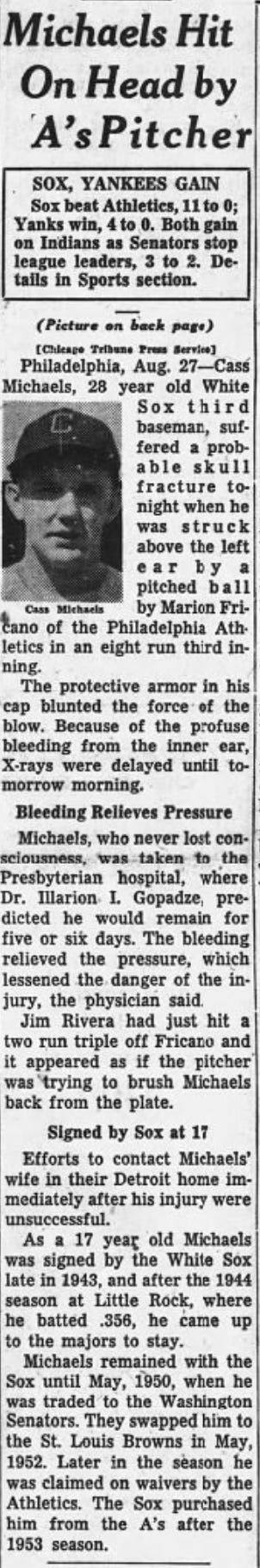

This frightening headline, and the accompanying article, seemed to presage the worst disaster in baseball since the beaning of Ray Chapman in 1920.

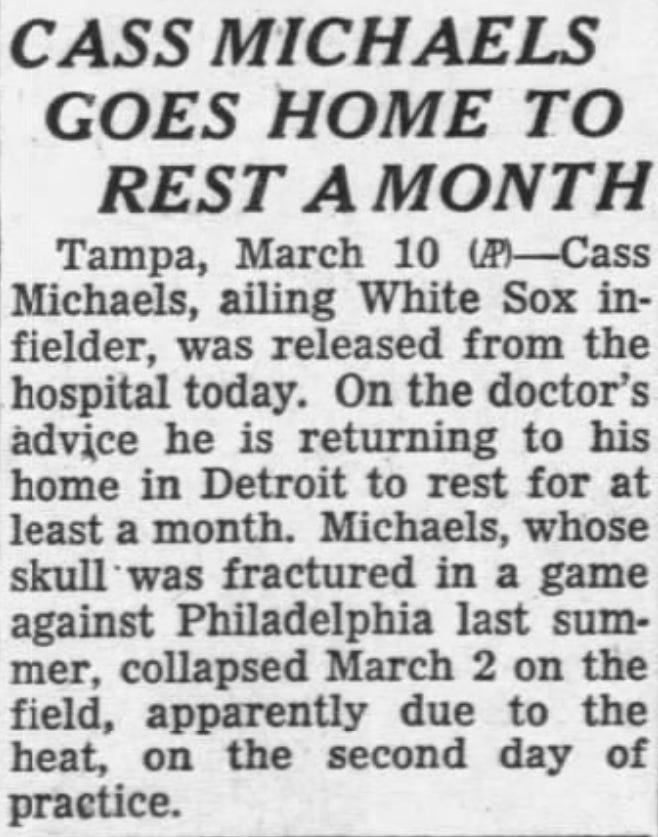

Michaels would never play another game of professional baseball. His vision was permanently damaged by the beaning, and he retired after collapsing in spring training in early 1955:

Michaels lived until November, 1982, when he passed away at the young age of 56.

Michaels’ Greatest Day

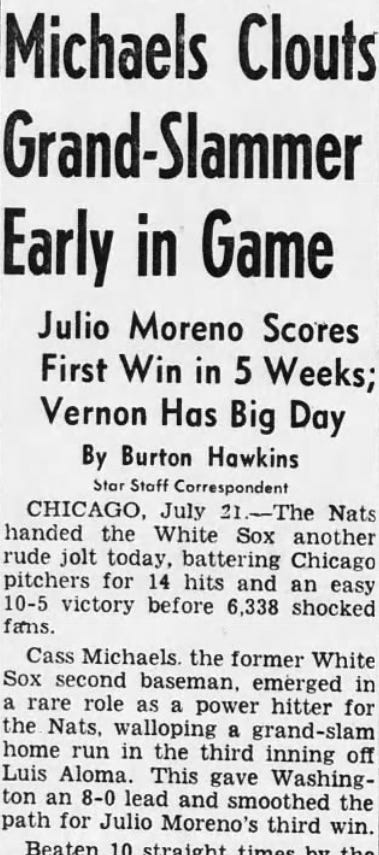

Cass Michaels’ greatest day in the major leagues was undoubtedly July 21, 1951.

Washington was in Chicago for a four game series. The White Sox were in the thick of the pennant race at that time, tied for first place with the Boston Red Sox and sporting a 53-35 record on July 19th. Washington, meanwhile, was down in 6th place and 15 1/2 games out.

The Senators won on July 20th, which set the stage for Michaels’ big blow on the 21st:

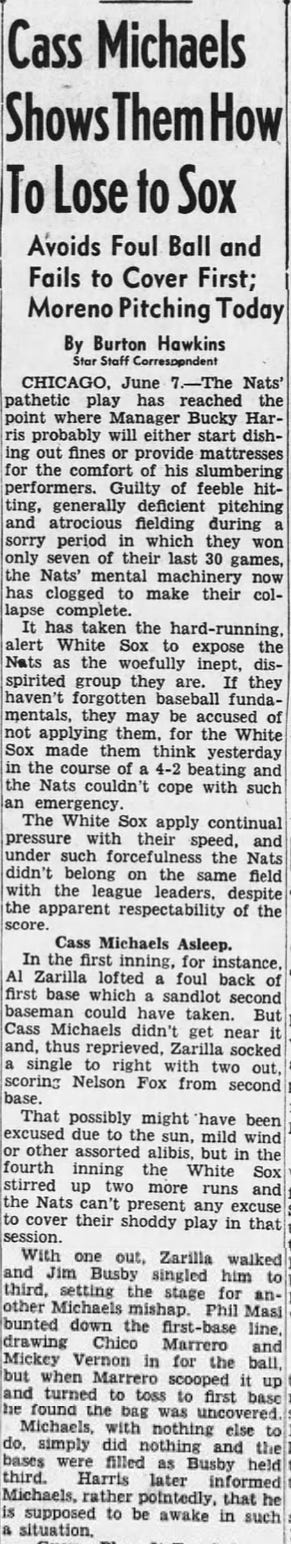

As far as the lowlights? Well, we won’t dwell too much on those…

One wonders what might have been in Michaels’ career had he stayed with the White Sox. He fell apart offensively after being traded, and never seemed to recover.

All this goes to show how important it is to research the players you are managing in your project. The guy you think is obscure and never amounted to anything might very well have been a much more important player than you thought.