What’s In a Name?

Do you ever wonder what the deal is with old fashioned baseball team nicknames?

The truth is that the concept of baseball teams having “official” nicknames is entirely modern. When we’re talking about the real old days, as in before World War I, nicknames were generally created by sportswriters who were looking to add some flair to their stories.

For example, in the Brooklyn Eagle story for the Boston at Brooklyn game on April 17, 1908, there is no mention of the Boston team being called the “Doves.” Here’s a snippet:

“Beaneaters” seems to be a more common nickname for Boston’s National League team — in the Brooklyn press, at least.

The Boston Globe, of course, completely contradicts my point:

At any rate, this goes to show you that “official” nicknames really aren’t a thing when you go back far enough.

Comeback

This game was a lot more exciting than its real life counterpart.

Boston got out to a quick lead in this one, scoring one in the first and one in the fourth. Brooklyn’s questionable offense did manage to put one across in the bottom of the 5th, but Boston equaled that with a tally of its own in the top of the 6th.

The score was now 3-1 Boston — a lead usually good enough to secure a victory in 1908. But not today.

The first Brooklyn comeback came in the bottom of the 6th inning. Tim Jordan led things off with a double. That brought up Tommy Sheehan, who promptly singled to left field. Jordan came flying around the basepaths, looking for a run to cut into the Boston lead. The throw from George Browne was right on the money, however, and Frank Bowerman tagged Jordan out.

Sheehan moved to second on the throw, but I thought that this would likely be Brooklyn’s last gasp. Harry Lumley slapped another base hit, however, and Sheehan scored, narrowing the gap to 3-2.

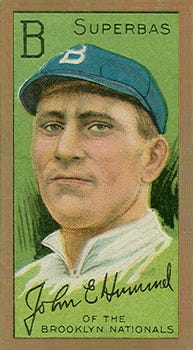

Up next came John Hummel. John hit a ground ball to Bill Sweeney at third base. I thought it would likely be a double play, but Sweeney was only able to get the out at second. That left Hummel on at first base with two outs.

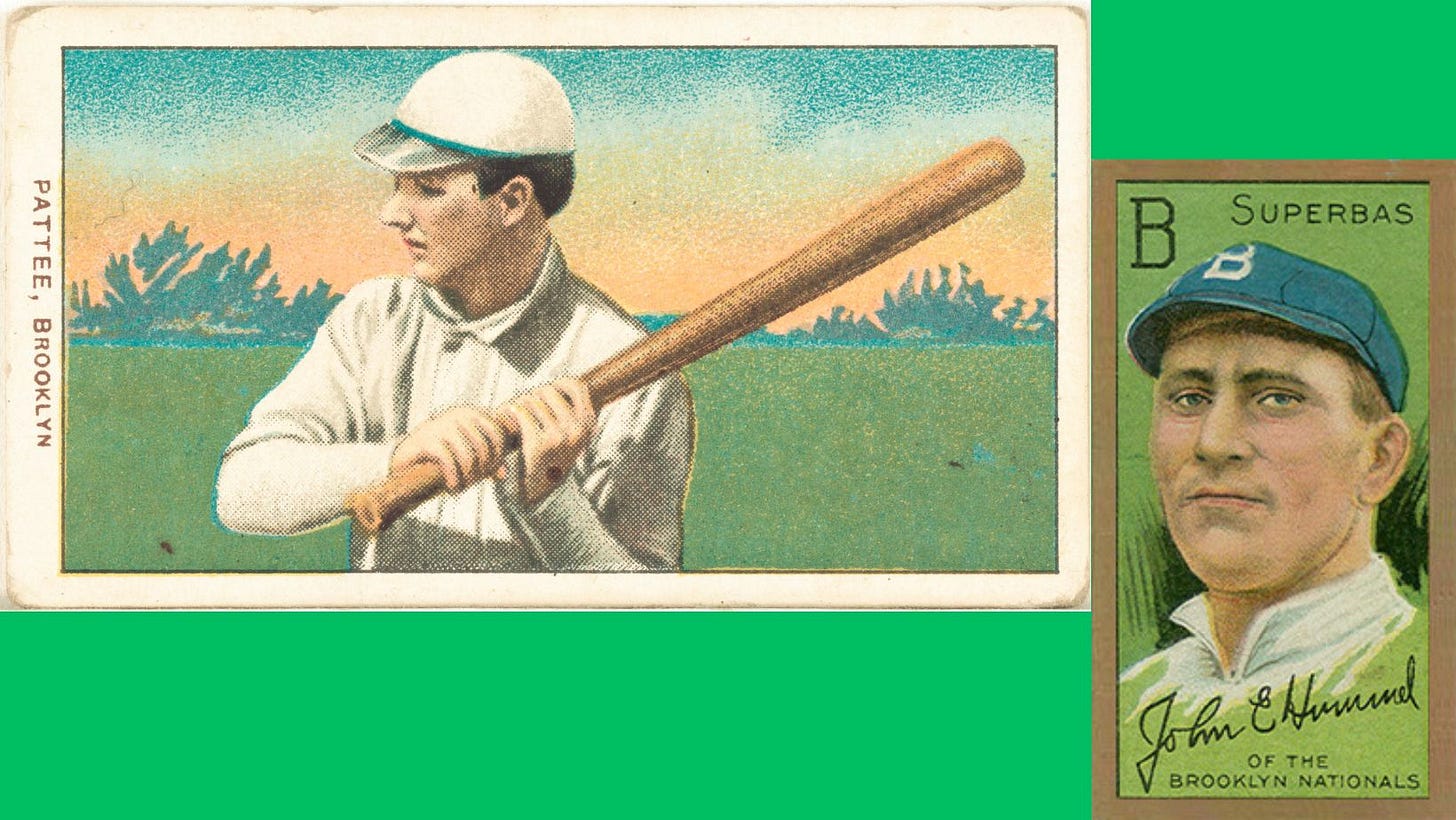

Though we’re still in the early stages of this replay, I’ve played enough 1908 games to know that a runner on first with two outs isn’t much of a threat. However, Billy Maloney singled for Brooklyn, sending Hummel to third. Maloney then added insult to injury by stealing second base with Harry Pattee at the plate.

Harry simply took charge, smacking a Patsy Flaherty pitch deep to center field, winding up on second with a double. By the time Phil Lewis finally made the third out, the complexion of the game had completely changed. Brooklyn was now leading, 4-3.

Seesaw

It wasn’t over yet, though.

Ginger Beaumont, one of those forgotten stars of the turn of the 20th century, came up with a runner on third base and two outs in the top of the 7th:

That single to left field tied the game at 4 — and there was still more to come.

Youngster Johnny Bates came up next:

Bates’ single to center field advanced Beaumont to third, opening things up for veteran Dan McGann:

Sweeney, the third baseman whose inability to start the double play had opened the flood gates for Brooklyn, flew out to Lumley in right, but the damage had been done. It was now Boston 5, Brooklyn 4, with only 9 outs to go.

Longball

Home runs are rare in 1908, right?

They might be rare, but they still do happen.

John Hummel, who hit that ground ball to Sweeney that just missed being a double play, came up with nobody on in the bottom of the 8th inning, down by a run:

And now it was 5-5.

I always ask myself whether the occasional 1908 home run was an out of the park home run or one that was actually over the fence. I could see this one being over the fence. Given the shallow right field of Washington Park II (about 300 feet according to this site), I could see it happening.

Regardless, the score was now tied, and this game was tense.

Drama

Leave it up to Boston pitcher Flaherty to cause all the drama.

I thought about taking Patsy out when I saw him leading off the top of the 9th for Boston. I decided to leave him in, after a bit of careful consideration. It’s 1908, of course, and it looked like he just might have something left in him.

I was thrilled when he singled. I also noticed that he had one of those (F) ratings, indicating that he was fairly quick. I decided to hit and run with leadoff man Claude Ritchey at the plate.

That was a mistake:

Ritchey rolled a “14,” which normally would have been a walk. However, because we were throwing caution to the wind and running the hit-and-run, it turned out to be a stolen base attempt. Sadly, Flaherty does not have a first column “11,” and he was gunned down at second for the first out.

And that ended Boston’s rally.

Brooklyn made two quick outs in the bottom of the 9th. However, catcher Lew Ritter managed to fight his way aboard with a base hit.

And that brought up Kaiser Wilhelm, who probably has the best nickname out of all the old time pitchers. Sure, his given name was Irvin Key — but he’ll always be remembered as the Kaiser of Brooklyn.

In a way that was almost unbelievable, both pitchers played a direct role in their own team’s offenses. Flaherty was on his way to goat status, and Wilhelm was only a few feet away from becoming a hero. It was all down to Tim Jordan again:

And that was that. Brooklyn completed the comeback, moving to 3-1 on the season. Boston, meanwhile, have to ask themselves just where this one went wrong.

I bet you weren’t expecting 22 hits in a 1908 game, were you? Sure, there is a lot of bunting and basestealing in these games — but there were offensive explosions every now and then, too.