Diamond Mind Baseball Statistics Guide: Individual Pitching

We’re back with more statistics from Diamond Mind Baseball, including some that are quite obscure. Let’s jump right in!

Basic Individual Pitching

Earned run average: We’re starting off with the bread and butter, aren’t we? This is the number of earned runs a pitcher has given up per 27 outs (or 9 innings). Here’s the formula:

The complicated part here is precisely what an “earned run” means. Again, Wikipedia has the clearest definition:

Now, when I read this I immediately have questions about whether pitchers might also have influence over their “unearned runs,” or, in other words, whether a pitcher might have some influence over errors behind him, or passed balls charged to his catcher. But those are questions that will have to wait for another day.

Strikeouts: Number of strikeouts

Walks: Number of walks allowed

Wins: Number of wins. Diamond Mind Baseball also shows us the number of losses.

Winning Percentage: Percentage of decisions (wins plus losses) that are wins.

Average run support: Average number of runs the team has scored for the pitcher during starts.

Batting average: The batting average of hitters facing this pitcher. We usually call this one “Batting Average Against” (BAA).

On-base percentage: The on-base percentage of batters facing this pitcher.

Slugging percentage: The slugging percentage of batters facing this pitcher.

Hits per 9 innings: Number of hits allowed per 9 innings.

Walks per 9 innings: Number of walks allowed per 9 innings.

Runners per 9 innings: Number of runners allowed per 9 innings. I haven’t seen this statistic used very frequently; usually we talk about the numbers of walks and hits per inning pitched.

Strikeouts per 9 innings: Number of strikeouts per 9 innings

Homeruns per 9 innings: Number of home runs allowed per 9 innings

Stolen bases per 9 innings: Number of stolen bases allowed per 9 innings. This works on that theory that batters usually steal pitches off the pitcher, not the catcher.

Shutouts: Number of complete games pitched in which the pitcher gave up 0 runs.

Quality starts: Number of times a pitcher went at least 6 innings in a start while giving up 3 runs or less. This statistic isn’t quite as meaningful for seasons that didn’t see high numbers of runs per games, or for years in which pitchers frequently pitched complete games. This is one of those arbitrary stats that don’t make much sense when you start thinking about it. Not surprisingly, it was developed by a sportswriter.

Quality start percentage: Percentage of all starts in which the pitcher pitched for at least 6 innings while giving up 3 runs or less.

Reliever Statistics

These aren’t quite as interesting for 1949, but are worth going over anyway.

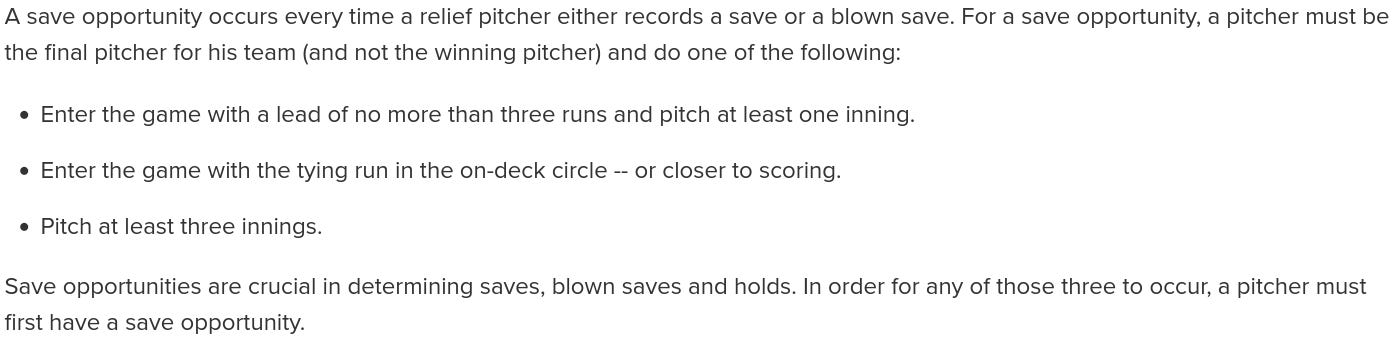

Save opportunities: Okay, this is where stuff gets weird. Instead of trying to explain this, I’ll point you to the official definition on the Major League Baseball website:

This is complicated, and is extremely arbitrary.

If you come into a game in which your team is leading by 3 runs or less and record 3 outs, you can get a save — and, therefore, you have a “save opportunity” when you enter the game.

If you enter a game with only 1 out to go and the tying run is on-deck, or at bat, or on base, you also have a “save opportunity.”

And, if you enter the 6th inning of a game in which your team has the lead, and in which you cannot get the win (more on that arbitrary stat later), you also have a save opportunity.

Can somebody please tell me why we make such a big deal out of a statistic that is so obviously made up?

Saves: The number of times a reliever does… one of those things listed above.

Save percentage: The percentage of save opportunities in which a pitcher gets a save.

Holds: Don’t like saves? Then you’re really not going to like holds.

Here’s what Wikipedia tells us about this arbitrary stat:

It’s kind of like the kid sister of the save.

Both saves and holds strike me as statistics designed to give relief pitchers something to help them make arguments during salary arbitration hearings.

That’s not to say that relief pitchers don’t play an important role. They absolutely do, especially in our world of constant pitcher injuries, kids trying to throw 150 miles per hour, and poor pitching management in general.

Look — you want to have a guy who can come in from the bullpen and put the game away. I absolutely agree with that. However, I don’t agree that we should have a complicated stat with a ton of exceptions and strangely specific rules that pretends to tell us something interesting.

One problem with relief pitching is that traditional pitching statistics don’t really tell the story. We’re going to run into that again and again when we really start digging into this. Spoiler alert: the real issue is sample size, or, in other words, the fact that relievers throw so few innings per year.

Blown saves: Save opportunities in which the pitcher didn’t get the save, usually because he gave up too many runs and lost the lead.

Blown save percentage: Percentage of save opportunities in which the reliever didn’t get the save.

More Pitching Statistics

These aren’t really “advanced” or “sabermetric” per say.

Innings: A measure of the numbers of innings pitched. An inning is defined as three outs. The number behind the decimal can only be a 1 or a 2, which is one of the strange things about baseball. 1 means one out and 2 means two outs. Personally, I think “outs” is a much better statistic than innings, though few people agree with me.

The nice thing about innings pitched is that we have this stat going way back into baseball history. One of the few constant statistics throughout the history of baseball is the number of outs in each game. As a result, outs has the potential to become a meaningful statistic in terms of normalization and cross-era analysis — something that few people have played around with.

Batters faced per game: Sort of like plate appearances, except turned around. This is the number of batters faced per 27 outs. You’d think that a higher number would be worse; I’m not sure why this is organized the way it is.

Complete games: Number of complete games pitched, whether you won or lost.

Doubles: Number of doubles allowed

Triples: Number of triples allowed

Homeruns: Number of home runs allowed

Stolen bases: Number of stolen bases allowed

Steal percentage: Percentage of successful stolen base attempts against this pitcher

Pickoffs: Number of runners picked off base — I expect this statistic will start to disappear now that “disengagements” are a limited thing in baseball.

Hit by pitch: Number of batters hit with a pitch

Wild pitches: Number of pitches that get by the catcher, allow a runner to move up, and are not considered “passed balls.” Wild pitches are a very arbitrary statistic in that sense. If nobody is on base, it’s not a wild pitch, even if it missed the plate by 100 feet.

Balks: Oh boy, balks. If you’ve got a runner on base and you pretend to pitch without pitching, you can be called for a balk. It’s intended to prevent pitchers from faking out runners unfairly, though the rule has been unevenly interpreted and applied over the years. See Wikipedia for more information. I’m not going to even try to rewrite that here.

Games: Number of games pitched

Starts: Number of games started

Batters faced: Number of batters faced

Games finished: Number of games finished — but not necessarily started.

Runners left scored percentage: Okay, this is where it gets a little bit odd. A “runner left scored” in Diamond Mind Baseball is a runner that the relief pitcher allowed to score that the initial pitcher left on base. According to the archaic earned run rules, the initial pitcher is responsible for that runner and can be charged with an earned run if he scores. The “runner left scored” count simply counts the number of times a runner left on by the first pitcher is allowed to score by the reliever. It counts against the first pitcher. This percentage is the percentage of those runners left on base who scored.

Inherited runners scored percentage: I’m pretty sure this is the exact same thing, except those runners scored counts here against the reliever, not against the initial pitcher. These two statistics are attempts to measure relief pitcher effectiveness — but, of course, the small number of innings pitched makes them of questionable value.

Ground Ball DP: Number of ground ball double plays pitched into. It seems that most sabermetricans these days consider this to have very little to do with pitching, though it was clearly not always that way.

Decisions: Numbers of wins plus numbers of losses.

Okay, we need to talk about this here. Both wins and losses are very arbitrary.

Per Wikipedia, here are the rules for wins:

Anytime you see something that requires the official scorer’s judgment, you can be sure that it is an arbitrary measure. Thankfully, wins have largely gone out of fashion. Of course, back in the days when complete games were more common, wins meant a lot more, and couldn’t be accumulated by “effective” relief pitching.

Losses are also somewhat arbitrary:

Losses: See above. Diamond Mind Baseball gives us losses first, followed by wins. The “leaders” are arranged in ascending order, with the fewest losses at the top.

Sabermetric Pitching Statistics

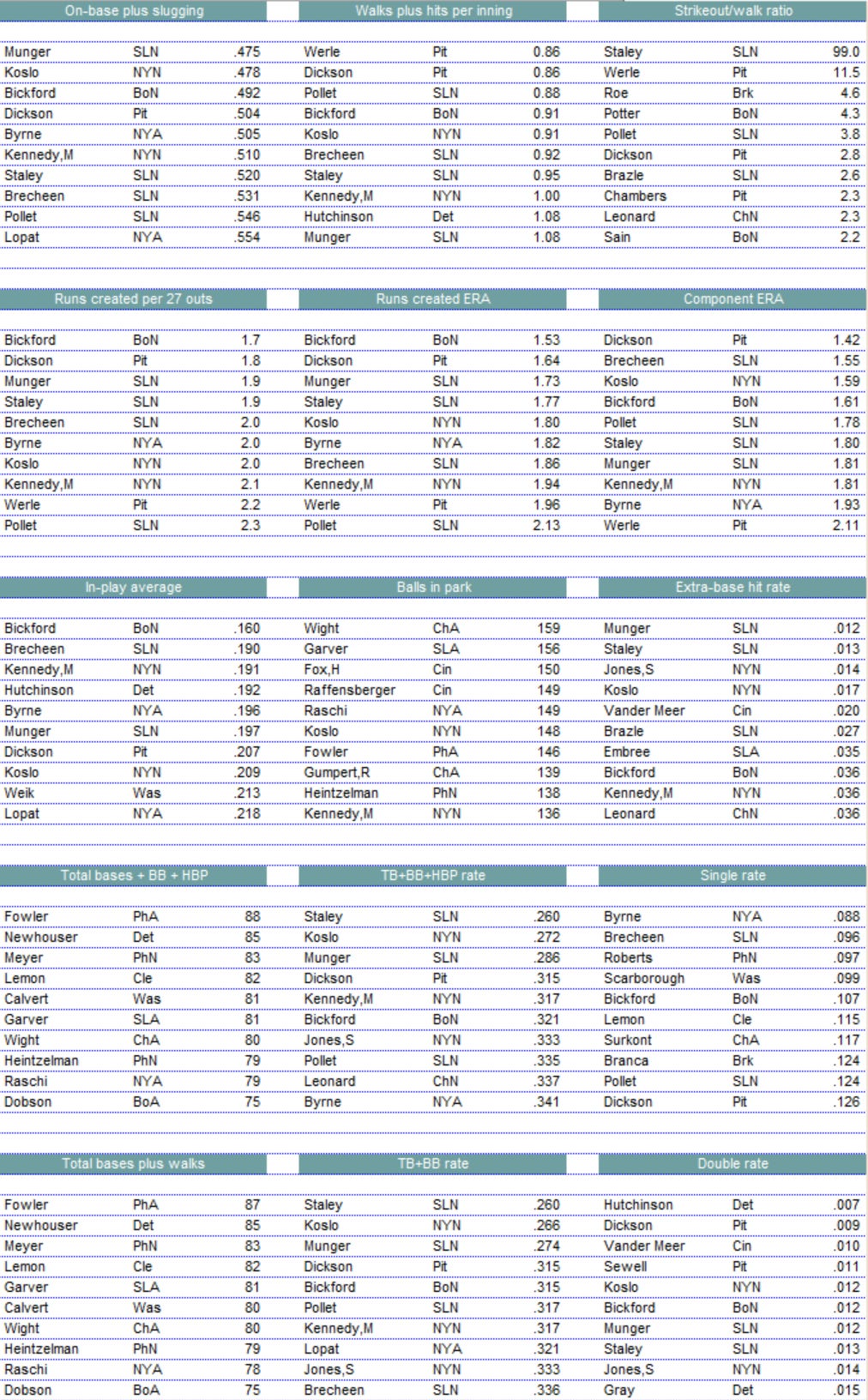

On-base plus slugging: Explained earlier in the batter’s section, this is exactly what it sounds like: the on-base percentage against the pitcher plus the slugging percentage against the pitcher. The lower this is, the better off you are.

Walks plus hits per inning: This is also known as Walks Plus Hits Per Innings Pitched, or WHIP. The lower the better. This is one of those bread-and-butter sabermetric pitching statistics that form the basis of almost all pitching discussions — well, until DIPS and FIP came around, that is.

Strikeout/walk ratio: Number of strikeouts per walk. 99.0 as shown above means that the pitcher has not given up any walks; it’s technically infinity.

Runs Created per 27 outs: Number of runs created by batters hitting against this pitcher, adjusted for a 27 out period. Once you understand Runs Created (see the hitting section), this one isn’t that hard to grasp.

Runs Created ERA: This should be the same as Runs Created Per 27 Outs, but it’s somehow different. This is calculated as runs created times nine, and dividing that total by innings pitched.

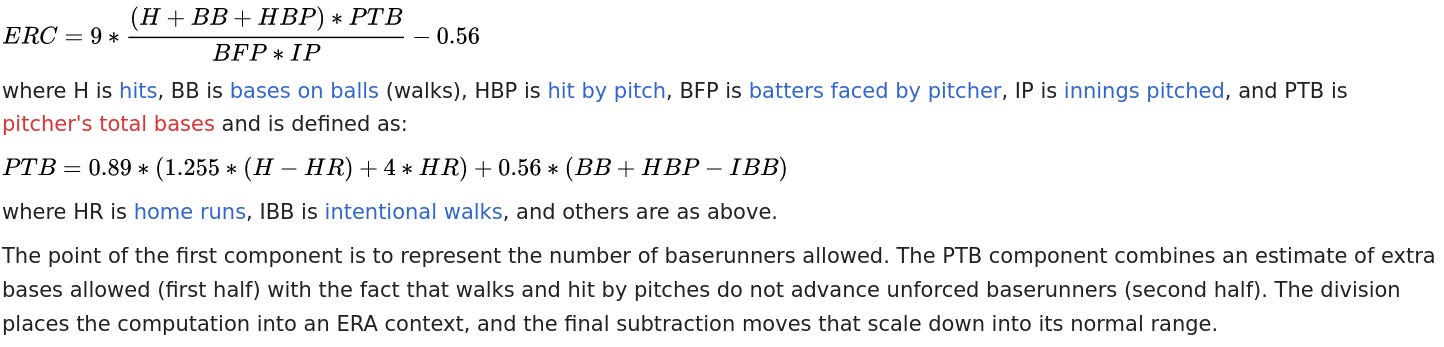

Component ERA: This is the expected number of earned runs allowed per nine innings by the pitcher. It’s basically an attempt to forecast earned runs allowed from the number of hits and walks allowed. Wikipedia gives us the formula:

Again — why 0.56? Why 0.89? Why 1.255? Who knows? I’m sure we can figure it out if we dig deep. As far as I’m concerned, I consider WHIP to be a much more reliable source of pitcher effectiveness.

In-play average: Here is your Batted Against Balls In Play (BABIP). This is the batting average on balls in play given up by the pitcher, excluding home runs.

Balls in park: Number of balls put in play that are not home runs.

Extra-base hit rate: Rate of balls put in play that are extra bases.

Total bases + BB + HBP: We see this quirky stat return again. I’m not sure what this is supposed to tell us about pitchers.

TB + BB + HBP Rate: The rate of total bases, walks, and batters hit by pitch, but on the pitching side.

Single rate: The number of singles given up divided by plate appearances. This shows the number of plate appearances that result in singles.

Total bases plus walks: Another odd stat reappears, again in pitching form.

TB + BB Rate: The rate of total bases and walks from the pitcher’s vantage point.

Double rate: The number of doubles given up, divided by plate appearances. Again, a stat of questionable merits.

Hopefully this has been somewhat helpful! We’ll look at those team pitching statistics next time.