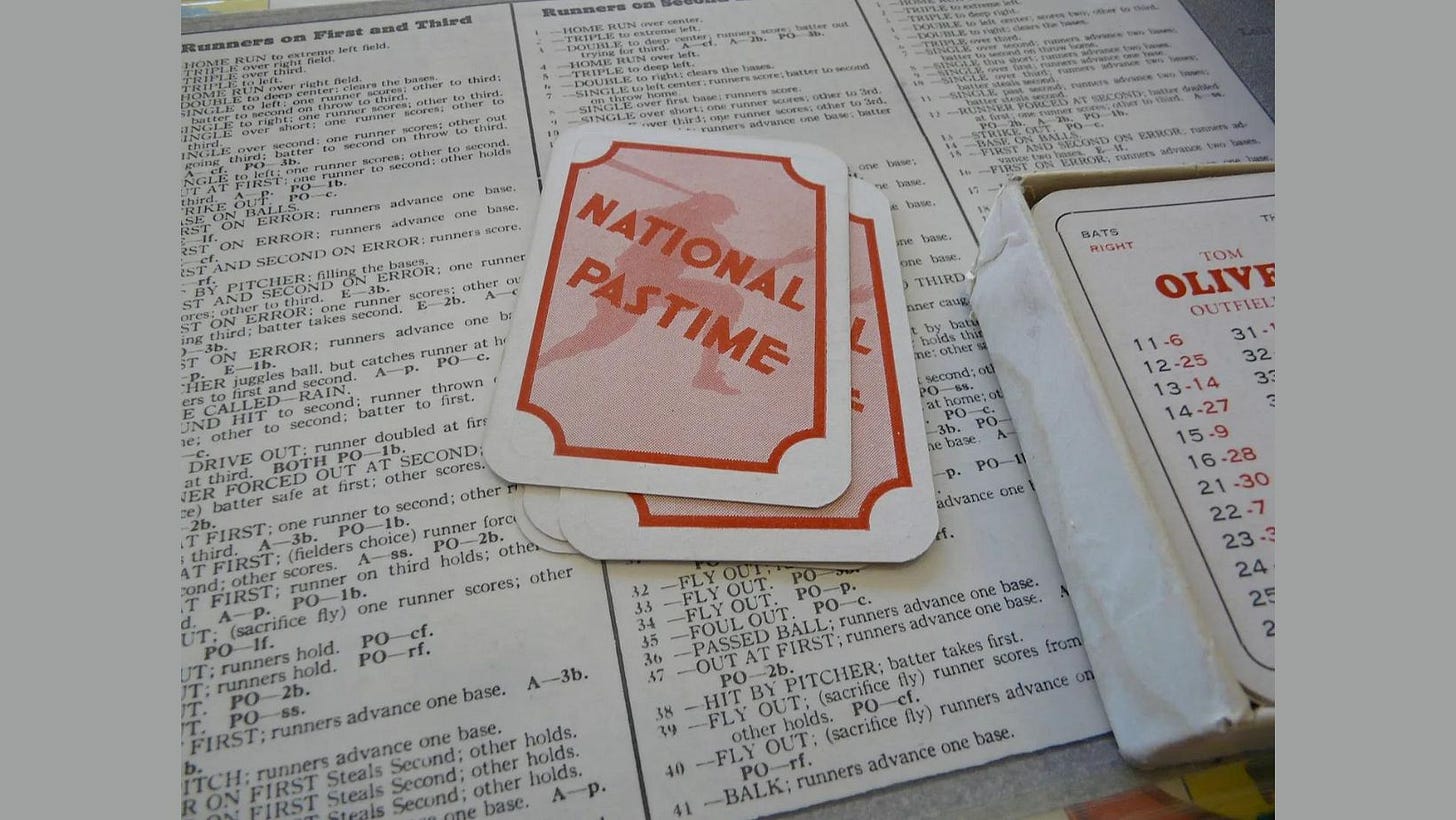

Dissecting National Pastime

I’ve been a little bit hesitant to write this post.

Once we started looking closely at Clifford Van Beek, I knew that I was going to have to start taking apart National Pastime to see what I could find. It wasn’t going to be enough to simply rely on the work that others have done.

I’m a bit nervous, however. There has been a lot of research and good work done over the years on the National Pastime game and cards — work done by people much smarter than I am. It’s kind of intimidating to figure out where to start and to think of what I can say. I’ve got this incessant feeling that somebody out there has already said whatever I’m going to say, and that someone has probably already proven every theory I’ve got wrong.

But we still need to dig in. And so here we go.

Chicken and Egg

We’ve got a bit of a chicken and egg problem to deal with right off the bat.

We know that Clifford Van Beek must have had at least some sort of idea as to how frequently each base situation came up. By “base situation,” I’m referring to bases empty, runner on first, runner on second — that sort of thing.

We know this because of the design of National Pastime.

You’d think that Van Beek would have taken the easy way out: that he would have create a Strat-O-Matic style game, for example, in which play results are written directly on the cards. Even if you grant the fact that many pre-1930 baseball games used different results for different on-base situations, you’d expect Van Beek to keep the results themselves more or less the same across boards.

We don’t see that in National Pastime, however.

Play result 3, for example, is a triple with nobody on base, but a double with a runner on first. Play result 4, in contrast, is a double with nobody on base, and yet a triple with a runner on first. If you get a 5, you get a double with nobody on base, and yet a home run with a runner on first.

There are similar patterns with the other play results. Play result 24, for example, is a double play with a runner at first, but only a single out with a runner on second. Play result 25, in contrast, is a double play in every situation with at least one base runner.

Though it is possible that Clifford Van Beek created these small differences in play results simply to make the game fun and enjoyable, I strongly suspect that he had at least some notion of the real life breakdowns for each of these situations. After all, if you play National Pastime you’ll discover that you actually don’t run into too many base situations with runners on second and third, for example. Things seem to play out in line with what we see in real life.

But first, before we can talk about this in more detail, we’ll need to talk about what those real life averages are. And that’s where we’re going next.

The chicken-and-egg dillema here lies between analyzing the boards and analyzing the real life statistics. Is there a way to easily look at the National Pastime boards and figure the odds for each on base situation? Do we think that Clifford Van Beek started with a game and fiddled with it based on his observation of baseball — or do we think that he started with some sort of real life observation first?

At any rate, we can’t really look into National Pastime cards and play around with averages until we’ve dug into the boards. And I don’t think we can do much with the boards until we at least know what “realistic” looks like in this situation.