Free Agency in OOTP

Free agency really should be a simple concept. The idea is that a player who does not currently have a contract can negotiate a contract with any other team.

This is more or less how the concept works in most sports leagues in the world. Since the famous Jean-Marc Bosman ruling in the mid-1990s, European soccer players can essentially move from one team to another upon the conclusion of their existing contracts. Veteran players of Football Manager learn how to anticipate when the contracts for key youngsters will end, and learn ways to jump in to take advantage of the situation.

But American sports are different, of course.

As I implied in my article about arbitration, baseball players are more or less stuck with their original teams for their first 6 years of major league service. While the “reserve clause” era no longer exists, the importance of major league service and the concept of using arbitration to settle disputes indicates that the market for players is still not fully free.

As a result, if you’re hopping over to OOTP from a game like Football Manager, you really need to slow down and understand the American “free agency” concept before you move forward.

Any one of the following three situations makes a player a free agent in OOTP:

Having an expired contract after playing in the major leagues for the minimum number of service years.

Having been released from his contract by the team (usually after a buyout has been paid).

Not having a current contract (i.e. a player from an amateur draft who was not drafted).

Note that players whose contracts expire before they hit the minimum number of service years for free agency will be given a league minimum contract automatically by the game.

Because of the second and third item, every single league setup will include at least some free agents. For example, if you start a historical game in 1934, include all minor league teams and players, and then manually delete the minor league teams and release all the players, every single one of those players will become free agents.

The first type of free agency, however, can be turned off. If you enable the “reserve clause era rules,” you can make it so that players will be forced to stay with their teams after their contracts expire.

You can also enable free agency for minor league players, which might be a nice way to break up teams that wind up with more good young players than they can actually use.

This leads us to the complex concept of draft pick compensation for lost free agents.

This thread on the official OOTP forums contains the best breakdown of the system I’ve been able to find.

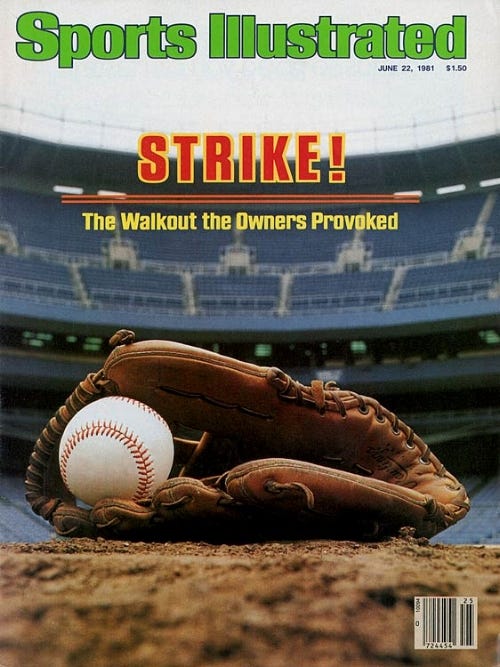

Before the 1981 strike, a free agent “re-entry draft” took place each season in November. Compensation for losing a free agent consisted of a draft pick from the signing team.

Now, the owners didn’t like this form of compensation, which led to the 1981 strike. The idea was that a draft pick was not sufficient compensation for losing a free agent. There was some demand for a system that likely would have made free agency in baseball look more like the old and familiar system of trades. On the surface, the idea seemed to be to promote competitive balance — but, in actuality, this was likely an attempt by owners to reestablish a semblance of the control over players they had once had but had lost.

In the end, the owners scored a limited victory on compensation for lost free agents. The post-1981 settlement was that teams that lost a “premium” free agent could draw from a pool of “unprotected” players from all clubs in the major leagues. This is what is known as the Type A / Type B system.

Type A free agents made up the top 20% of all players.

Type B free agents made up players from the top 21% to the top 30%.

All other players were unranked.

If you lost a Type A player, you could pick a player from a compensation pool of “unprotected” players, and would also receive a draft pick from the team that signed the free agent. Losing a Type B player meant a draft pick alongside an additional “special” draft pick from between the first and second rounds of the draft.

The Type A / Type B system was modified a few times over the years, but the basic concept remained the same. OOTP’s A/B system is loosely based on that post-1981 system.

Now, it’s also important to understand that this is not the system MLB currently uses. MLB teams currently receive compensation only in the form of a draft pick. Precisely where that draft pick takes place depends on a few variables thanks to the luxury tax rules — which, as I’ve discussed earlier, realy aren’t much of an impedement to teams like the Dodgers buying up all the good free agents anyway.

To receive compensation these days, the team losing the free agent must make a “qualifying offer” to the player first. This is defined as a one year contract worth a salary that is at least equal to the average of the 125 highest MLB salaries as of August 31 of the season most recently concluded.

And, yeah, that’s a handful.

By the way — this complex and bizarre system is simply the natural result of Major League Baseball sticking stubbornly to the old Gilded Age National League system. As long as Major League Baseball continues to have monopolistic control over the highest level of baseball in the United States, we will continue to see these bizarre attempts to shape the market for its players.

And, sadly, I’m not aware of a way to create a Football Manager style financial model in OOTP.