How Accurate Were Clifford Van Beek's Lineups? — Part One

Looking at the National Pastime American League Lineups

Before we begin, I want to give a shout out to my friend Bernard Stoum, who saw Roger Clemens throw a no-hitter in his 1986 Red Sox Diamond Mind Baseball replay. You can read a summary of the game and see the boxscore here. Congratulations, Bernard!

National Pastime Lineups

There was a lineup sheet with the National Pastime game.

The existence of the sheet itself was a matter of controversy for some time. In fact, there was no real confirmation that there was an original lineup sheet until it was found in the papers of the late J. Richard Seitz, as Scott Lehotsky explained in The APBA Journal over 25 years ago:

Now, if you’ve been following along carefully, you’ll notice something interesting about these lineups. Although Van Beek’s cards did not contain position information, his lineup sheet did.

Let’s take a closer look.

Clifford Van Beek’s American League Lineups

I’m going to divide this post up into two parts. Rather than mince words, we’re going to go through the National Pastime recommended lineups, team by team, and will compare them to what was used in real life.

My suspicion is that Clifford Van Beek kept track of lineups as the year went on, probably through boxscores in The Sporting News. Before we can arrive at any sort of conclusion, though, we want to see just how accurate his lineups were.

We should keep in mind the caveat that Van Beek included at the top of his roster sheet:

We’ll look at the American League today, team by team. We’ll follow up next week with the National League.

Philadelphia Athletics

First, we’ll look at the National Pastime recommended lineup:

Then comes the most common batting orders per Baseball Reference (which, as you know, comes from a compilation of all official boxscores from 1930, as well as complete play-by-play data for numerous games):

And, finally, we’ll look at the most common starting defensive lineups, also per Baseball Reference:

As you can see, Van Beek got the players exactly right. Haas and Dykes were swapped in the batting order; however, when we look at the game-by-game batting orders, we see that Dykes started hitting 2nd on September 3rd and stayed there for the rest of the season:

Dykes did not hit 2nd before September 3.

Note that Van Beek’s fielder placement is right on, including the outfielder positions.

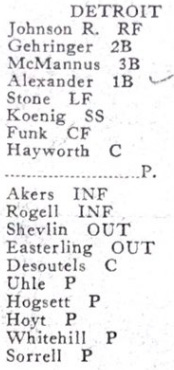

Detroit Tigers

This is where the fun starts.

Detroit never used Van Beek’s specific lineup. However, this is a good reflection of Detroit’s average batting order in 1930:

Bill Akers had 233 at bats in 1930, falling just short of Mark Koenig’s 267. I’m assuming that this is why Akers wound up on the bench for Van Beek. Note that I use at bats because plate appearances were not measured as an official stat in 1930: Van Beek would have used at bats.

The only other potential quibble I see here is Billy Rogell, who technically hit 7th more than any other player. He only had 144 at bats, however, which relegated him to the bench.

Again, the defensive positions are right on.

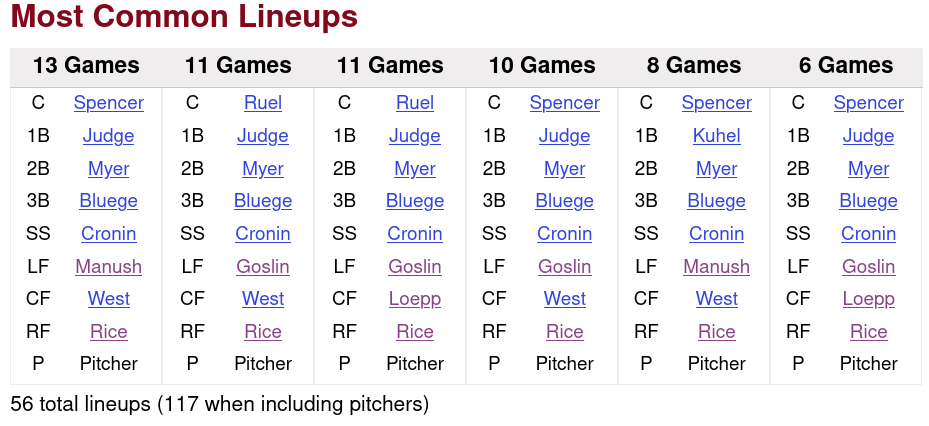

Washington Senators

Van Beek nails the most common lineup for the Senators. Once again, the defensive positions are exactly right.

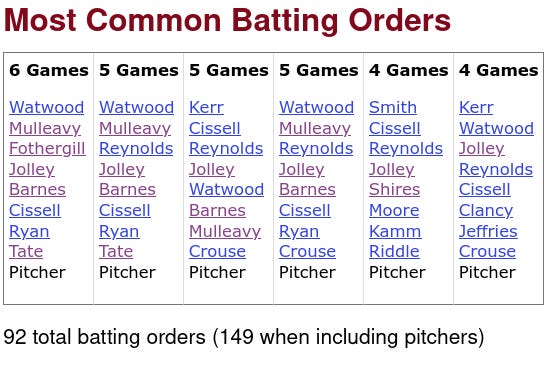

Chicago White Sox

You must be thinking that you’ve got me here. Van Beek’s 1930 White Sox lineup doesn’t look anything like those common batting orders, right?

Here, again, are the players that most commonly appeared in each batting slot for the 1930 White Sox:

Red Barnes winds up on the bench instead of in the 5th spot chiefly because he was an outfielder. Barnes played center field in 1930, but only wound up with 266 at bats, compared with the 422 Johnny Watwood had. Remember that Barnes was traded to Chicago from Washington in mid-June, which had an impact on how many times he started for the White Sox.

Watwood is pretty interesting, too, with 61 starts at first base and 41 in the outfield. Bud Clancy, who Van Beek used as the White Sox starting first baseman, had 234 at bats in 1930 and made 59 starts at first base.

There’s a good argument that Van Beek should have had Watwood starting at first, Barnes starting in center field, and Clancy on the bench. However, if Van Beek had some sort of running tally of the number of times each player started in each lineup position, you’d expect him to go with Clancy starting instead. After all, he started in the 6th spot more than any other White Sox player.

Hitting Tate in the 7th spot makes no sense, and should be chalked up as a mistake on Van Beek’s part.

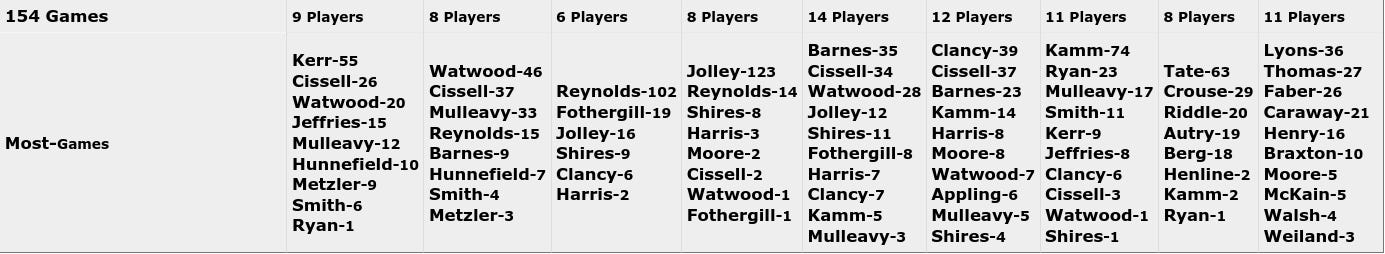

What about the defensive positioning? These are the defensive positions that the White Sox used most frequently in 1930:

The biggest question here is probably Van Beek’s decision to list Bill Cissell as a shortstop instead of a second baseman. Greg Mulleavy seems an obvious choice for shortstop in terms of games started, and was also carded.

There’s a lot going on with this team, including more than meets the eye here. Van Beek’s decision to create a card for Moe Berg as a third catcher might very well be the strangest roster decision he made. In the interest of space, I’ll go into more detail on the White Sox conundrum in future posts.

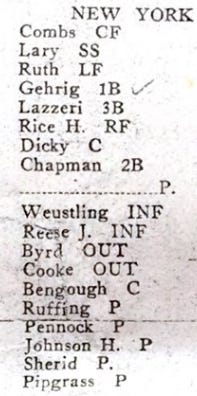

New York Yankees

Van Beek gets the batting order perfectly right for the Yankees. There are a few issues with the outfield positions, and I think most casual baseball fans would scoff at the idea of Babe Ruth playing left field.

Ruth did play left field on occasion in 1930, however. The big mistake here is putting Rice in right field, where he never played in 1930. Here are the Yankees outfielder arrangements for 1930:

Switch Rice to center field, Combs to left, and Ruth to right, and you’ve got it exactly right.

Boston Red Sox

The Red Sox are another example of Van Beek creating a batting order that didn’t take place in real life, but that looks awfully close to what happened in September. Here are the Red Sox batting orders in September 1930:

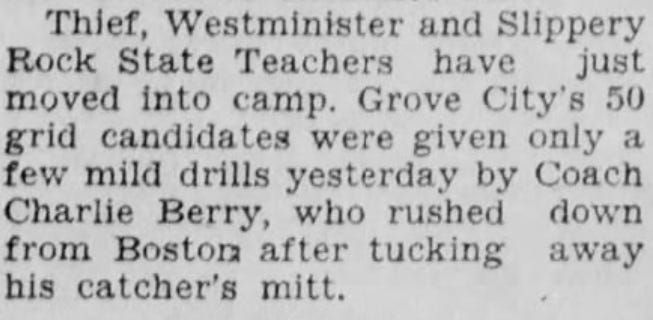

The player that prevents Van Beek’s lineup from being real is Charlie Berry. Berry appears to have left the Red Sox after the September 1 doubleheader to coach college football at Grove City College in Pennsylvania:

I’ve got a feeling that most 1930 transaction lists don’t have that one.

Again, Van Beek’s defensive positions are right on.

Cleveland Indians

Here we see a number of differences.

First off, here are the number of times each player hit in each batting order slot, per Baseball Reference:

The lack of initials make this difficult. Catcher Luke Sewell hit most often in the 7th hole, while third baseman Joe Sewell hit most often in the 2nd or 6th slot.

Ed Morgan’s slot is kind of a tossup between 1st, 3rd, and 4th. Van Beek went with the 4th hole for Morgan, which caused Charlie Jamieson (misspelled as “Jameison” on the roster sheet) to hit 1st. With that in mind, Johnny Hodapp hitting 5th doesn’t seem too strange — and, as was the case with the White Sox, it seems that Van Beek mixed up catcher Sewell with shortstop Jonah Goldman for the 7 and 8 spots.

Lineup oddities aside, Van Beek got the fielding positions right on once again, including the outfield spots.

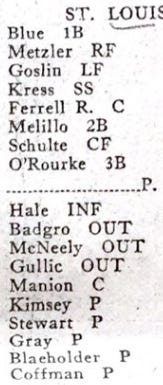

St. Louis Browns

Van Beek got the batting orders right on, and the only potential lineup quibble is his choice to stick Frank O’Rourke in at third and Red Kress in at short. However, when we look at the positions most commonly played by the Browns players, we see why Van Beek did this:

O’Rourke played more frequently at third base, and Kress played more frequently at shortstop. It just so happens that they were switched around for those 14 games in which the Browns put out their most frequently used lineup.

In short, Van Beek was absolutely right again.

Conclusion

There’s no need to mince words here.

Van Beek got the lineups and defensive setups exactly right for the following teams:

Philadelphia Athletics (for September, at least)

Washington Senators

St. Louis Browns

The New York Yankees would be on this list of Rice weren’t listed as playing in right field. I suspect that Van Beek may have made a transcription error. It’s a minor quibble.

The Detroit Tigers are extremely close, and argue for the idea that Van Beek was copying lineups down in some sort of ledger. Their National Pastime lineup was never used, but makes sense if you start off with the players with most at bats listed at their positions and try to make it fit with where they hit in real life.

The Cleveland Indians would also be really close to that list if Van Beek hadn’t mixed up Luke Sewell and Jonah Goldman.

And the Boston Red Sox would have been on that list had Charlie Berry not gone off to coach college football in early September, once he saw the major league team was doomed for the cellar.

That leaves only the Chicago White Sox. There’s a lot happening with the White Sox; we’ll talk about them later.

We will go over the National League lineups next time, after which we’ll talk about how in the world Van Beek could have gotten these lineups right. It’s a remarkable feat, especially for 1930.