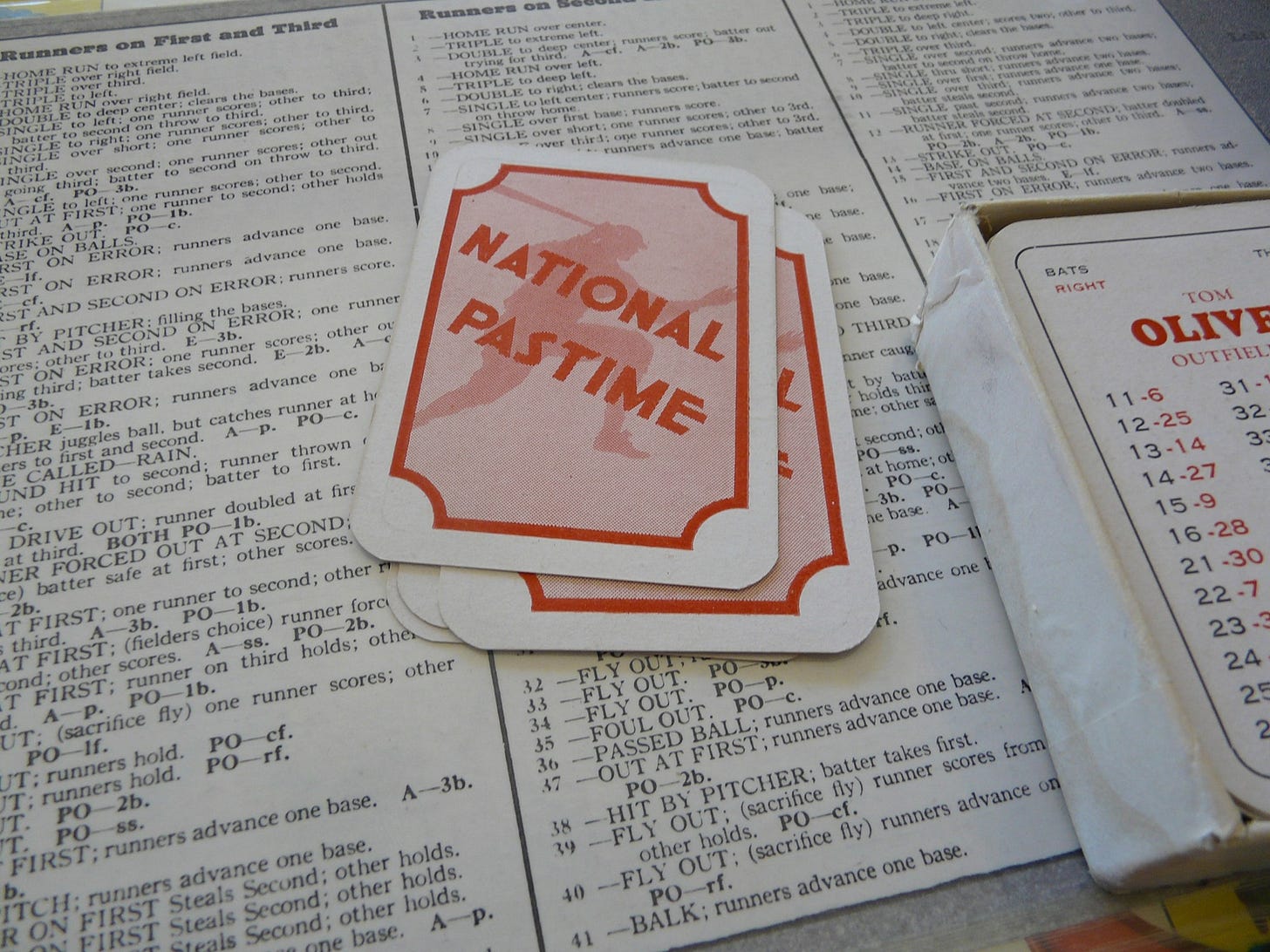

The National Pastime Mysteries

I’ve identified 4 mysteries surrounding National Pastime.

Now, I’m not an expert on this stuff. I don’t have definitive answers. However, I do think I’ve come across some information that might add to this discussion.

This is a discussion that has taken place slowly over the course of many decades. It started in the mid-1970s, and continues to this day, though mostly in the arcane corners of internet message boards.

The first mystery we’re going to try to address is just how many National Pastime games were actually sold.

The Bankrupt Printer

I’ve got to get something off my chest here.

Clifford Van Beek told people that National Pastime failed because his printer went out of business.

That simply is not true. It’s not true, and I can prove it.

Finding the Real Clifford Van Beek

Old newspapers can tell you a lot of things.

There are a few old clippings about Clifford Van Beek in the old Wisconsin newspapers. You can find interesting odds and ends, like the time in 1926 when he ran over a pedestrian:

It doesn’t sound like Van Beek was going too fast, thankfully.

There are reports that Clifford Van Beek was a grocer by trade. I believe it, especially since he apparently started a basketball team called the Grocers in early 1927:

While I was sorting through all of this, looking for more evidence of Clifford Van Beek the man, I came across an article that was really surprising.

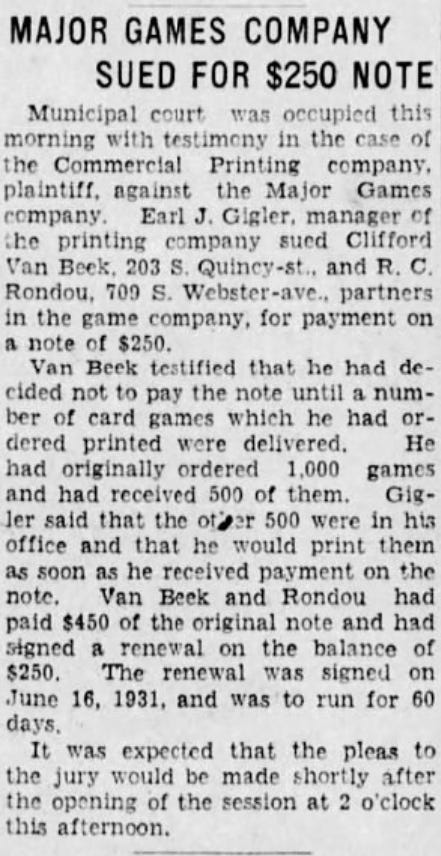

The Lawsuit

Clifford Van Beek was apparently sued by his publisher in early 1932.

I bet you’ve never seen this before, even if you consider yourself an expert on all things APBA:

Okay: let me explain to you why this is important.

First of all, we know for a fact that this is that Clifford Van Beek. We know this because we know that his game company was called Major Games Company. I sadly don’t know anything about R. C. Rondou, who I am afraid is doomed to become an extremely obscure historical footnote in this story.

See, for example, this original National Pastime advertisement, which ran in The Sporting News on December 11, 1930:

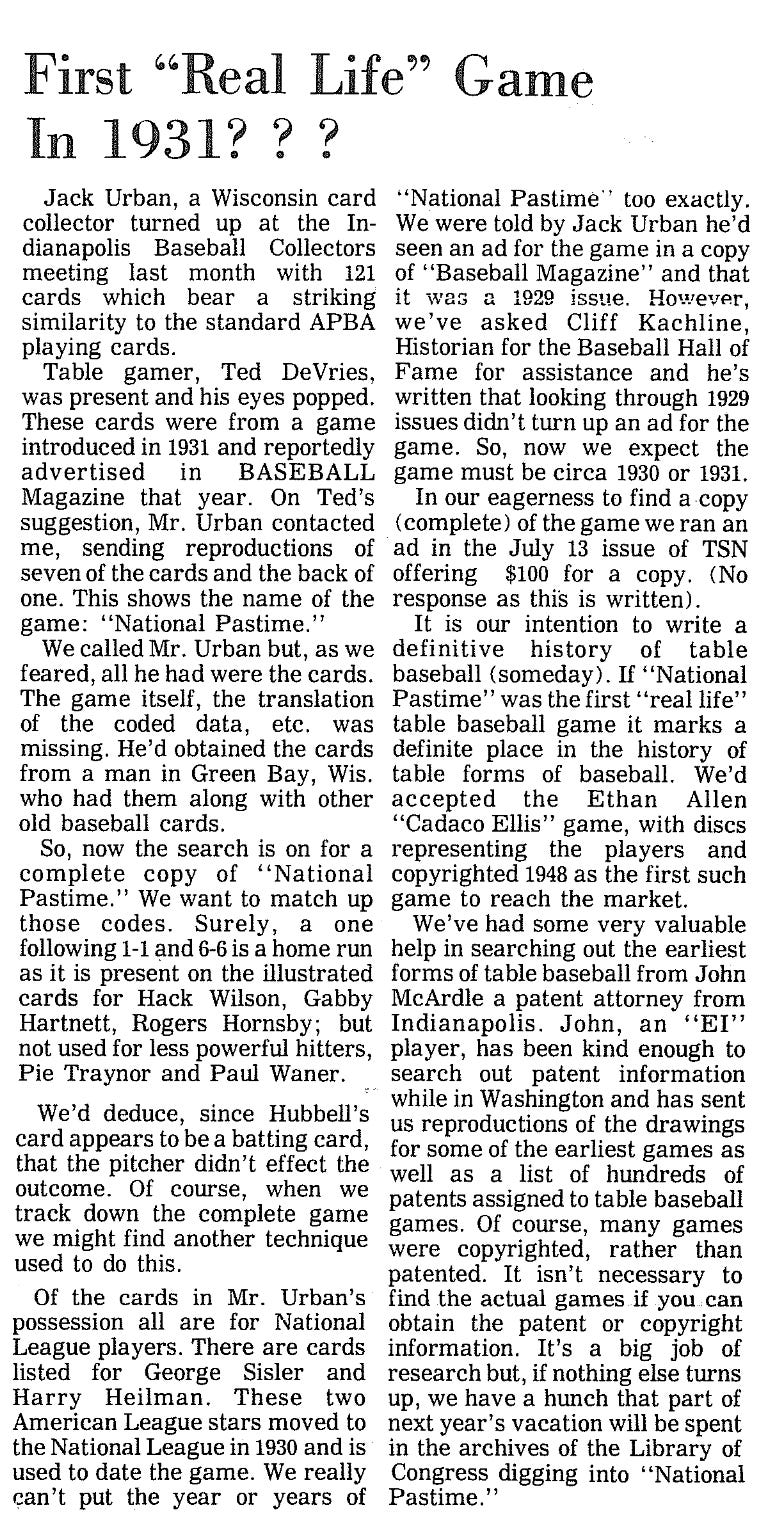

Now, we also know bits and pieces about this story from other sources. This comes from the original APBA Journal expose on National Pastime, which came out in late 1976 to the shock of the entire community:

I also cited an old Strat-O-Matic Review article from 1978 last time, which has this to say about the bankruptcy incident:

You can see the contradiction here, right? I mean, did he order and pay for 2,000 games, or just 1,000? Were 800 delivered, or were 400 delivered?

There’s also this bit from a later APBA Journal article:

Now we’re back to 500 games sold.

You’ll also notice that the story has always been that the printer went bankrupt. Nowhere is it mentioned that the printer actually sued Clifford Van Beek for not paying for the remainder of his games.

Oh, and by the way: Van Beek lost that lawsuit.

The Printer Never Went Bankrupt

Remember that bit about the printer going bankrupt?

I don’t believe it.

In fact, I think it was Clifford Van Beek who went bankrupt after he was unable to sell his games.

I was easily able to find numerous references to Earl J. Gigler in the old Green Bay newspapers. See this from May 1932, for example:

That doesn’t look to me like a business that just went under. The address is the same. You could consider this to be an advertising piece — but you need money to advertise. Employing 20 men in 1932 makes it clear that this wasn’t some small obscure printer, either — although this is usually assumed with the Clifford Van Beek story is told.

If we go back a little farther, we can actually trace Gigler’s company. Here’s a piece from 1926:

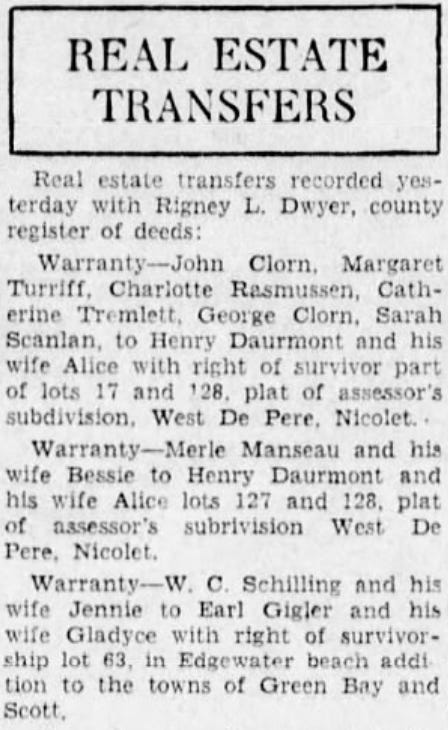

In fact, Gigler was so successful that he was buying property in October 1930:

There are other articles about Gigler mingling with high society — though, for the sake of fairness, similar articles exist about Van Beek. That’s right: despite his orphaned state, Clifford Van Beek’s name comes up fairly frequently in the newspapers in association with various parties and other major social gatherings.

For me, though, this one settled the press shop question for good:

Not only was Gigler still in business under the same name, but he was also able to score a large and lucrative government contract in mid-1942.

I’m convinced that the printer never went out of business. I believe that Van Beek’s game simply didn’t sell, and that the debt he owed to the printer put him out of business.

The National Pastime Enigma

There is simply no way that 500 copies of National Pastime sold.

We would have found more cards by now if that were the case. With the growth of interest in baseball cards in the late 1970s, surely somebody would have seen another version of this game for sale somewhere.

The truth is that National Pastime is extremely rare. It’s incredibly rare. It’s so rare that even the most ardent collectors had never heard of it.

The editor of Extra Innings Newsletter learned that way back in 1974:

As recently as 1997, nobody could find a copy:

I cut that paragraph off on purpose. Author Scott Lehotsky goes on to explain that Howard Ahlskog remembered seeing a copy of National Pastime for sale in western Massachusetts in the late 1970s for $1,000, but wasn’t sure if it was even complete.

The APBA Journal concluded that there were only 2 known original copies of National Pastime as of 1997, and neither were complete. The copy that the Van Beek family had was missing the lineup sheet. Meanwhile, Lehotsky and others with The APBA Journal discovered that J. Richard Seitz apparently had two copies of the game, including two copies of the playing board (one used and unreadable, the other clean), two copies of the lineup sheet, and all but about 15 of the original cards.

And that’s it. The only other cards we have left to speak of came from random people in the Green Bay area, who apparently sold them at the regional baseball card shows that started popping up in the mid-1970s.

I’ll be blunt. I don’t think 500 copies of this game sold. In fact, I don’t think 100 copies of this game sold. I think that Van Beek’s game failed miserably, and I think that’s why he couldn’t pay his printer.

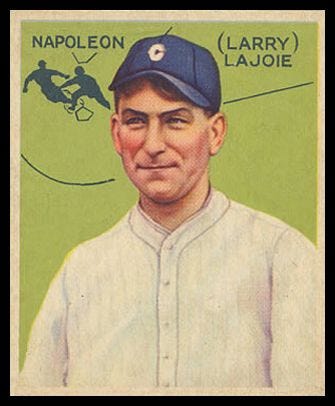

500 copies isn’t much, but it’s also not nothing. Take the famous 1933 Goudey Napoleon Lajoie card, for example.

It wouldn’t be out of the question to assume that 500 or fewer of these cards were printed. When you understand the printing methods, you’ll see what I mean. These were short printed, and were designed to be short printed. Heck, they didn’t even come out in 1933.

And yet something like 120 of these cards have been graded.

I don’t think you could find 120 original copies of a single National Pastime card if your life depended on it.

The famous T-206 Honus Wagner card supposedly didn’t even have 100 copies printed.

And yet dozens have survived.

Now, I know you’re going to say that this is different, but I also want to point out that the famous Alpha Black Lotus, the rarest and most desirable card from the first Magic: The Gathering run, saw only a little over 1,000 copies printed.

Magic: The Gathering fans always estimate that about half of that original run was destroyed, either due to carelessness on the part of players, teachers and parents confiscating “evil” cards, and other shenanigans.

And yet over 100 of those have been graded by PSA alone.

Given what I know about collectables, I simply can’t accept the idea that 500 copies of National Pastime sold. If that were true, we’d see at least something moving on the secondary market.

Aside from the Seitz estate set, the only secondary market movement we know about is a rumor of something in the late 1970s, preceded by a purchase of an incomplete set in 1974. That’s it.

The Math

The math also doesn’t work out.

Van Beek sold his game for $5, or $3 for either league if that’s all you wanted.

If he actually sold 500 games, he would have netted $2,500.

There’s no way he would be taken to court over a $200 debt if he had sold all 500 games. Not unless the cost of advertising in The Sporting News and Baseball Digest in winter 1930-31 cost him thousands. And I simply don’t believe that.

That is the reason why I think Van Beek’s game is so extremely rare — even more rare than obscure titles from two decades earlier, such as the Fan-I-Tis game that The APBA Journal was mysteriously obsessed with in its final years. It’s rare because it simply didn’t sell. It was a total flop.

And yet, in the end, it gave birth to an industry that has become huge.

I suspect that most copies of National Pastime were destroyed. I think that some were likely given away to Van Beek’s friends, which is probably why that collector who held the cards in 1974 was from Wisconsin. We know that Van Beek kept one copy of the game (though it was incomplete, without the lineup sheet), and we know that Seitz somehow had two copies of the boards and lineup sheet. And that’s all we know for sure.

This was extremely well done and very interesting.