How Much Of Baseball Is Pitching?

Connie Mack supposedly once said that pitching is 75% of baseball.

But there’s a problem with that statement. Nobody knows the source.

You can find people attributing it to Connie Mack as early as 1949:

Look any earlier, however, and the picture gets quite muddy.

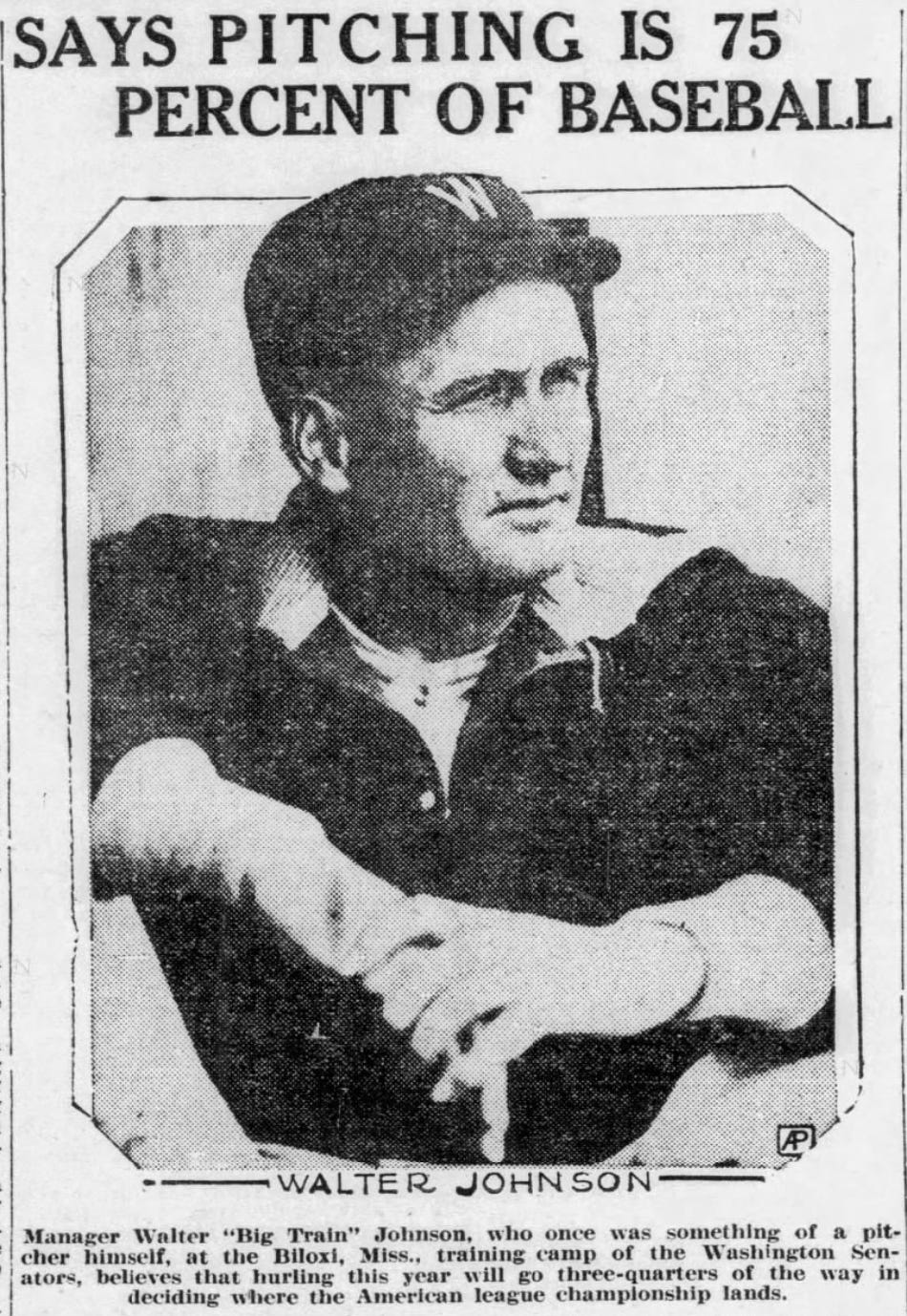

Walter Johnson apparently made that statement long before people think Connie Mack made it:

The coolest, and earliest, record of this assessment, however, comes from a preview of the 1927 World Series. Here’s the whole article for your viewing pleasure:

That article came underneath this montage of Murderer’s Row:

And here’s the relevant quote:

Now, if the 1927 World Series is any guide, it’s pretty obvious that pitching is not 75% of baseball. But, of course, sportswriters generally don’t have the time to look backwards to assess their mistakes and learn from them. Instead, it seems that they tend to take their ridiculous claims and attribute them to famous people who likely never even thought what they supposedly said.

The reason why I’m bringing all of this up is this small bit from the 1981 Baseball Abstract:

Let’s see if we can illustrate this point. Gene Tenace, who usually is named in those WAR arguments you see on Twitter, walked in an astounding 22.1% of all his plate appearances in 1980. In general, about 8.2% of all plate appearances in 1980 ended in a walk. As you probably already know, Tenace had a really good eye, and tended to walk far above the average rate in every single one of his Major League seasons.

The highest player pitching ratio in 1980 belonged to Steve Mura, a 25-year-old pitcher who never really learned how to throw strikes. He walked 12.0% of all batters he faced in 1980.

Let’s see if we can find someone more extreme. If you’re only going back to 1900, the all time leader in walks given up in a single season is Bob Feller in 1938. Feller, who was only 19 years old at the time, gave up a whopping 208 walks, which means that he walked 16.7% of the batters he faced.

Maybe he shouldn’t count. Next on the post-1900 list is Nolan Ryan, who gave up 204 walks in 1977. And yet that totaled up to “only” 16% of Ryan’s batters faced walking.

So James is right. You could repeat this exercise with any of the statistical categories he lists, and he’ll still be right.

I’m sure you can find pitchers with crazy BB% stats, of course. If you find guys who pitched maybe an inning or two, you’re sure to find them.

Part of it is a sample size issue. Nolan Ryan faced a whopping 1272 batters in 1977; in 1980, Gene Tenace only had 416 plate appearances. The smaller that number (batters faced or plate appearances) is, the more likely it is that you’ll get a big percentage.

Of course, that doesn’t invalidate James’ point.

But does this really mean anything about what percentage of baseball is pitching?

My gut tells me that not even 75% of pitching is actually “pitching.” You’ve got a lot of things happening that lead to traditional “pitching” statistics.

Assuming the batter makes contact, the ball is fair, and it’s not a home run, you’ve got 8 other guys scurrying around the field trying to make an out. And if you’ve got Dante Bichette out in left field, and your incompetent management decided that Darryl Hamilton would make a good center fielder next to the immobile Bichette, your pitchers are going to look pretty bad when anything hit to the left-center field gap is a double or triple.

It’s not going to be an “error” if Bichette is nowhere near the ball, of course. And, as anybody who has seen what his 1999 fielding performances look like already knows, Bichette isn’t getting to any ball not hit directly at him.

In other words — a lot of “pitching” is actually fielding.

The same goes for the strikeout artist, or the guy who walks everybody. Until we finally roll out the robotic umpire system, framing pitches will always be an important catching skill. A good catcher can turn a ball into a strike literally with a flick of the wrist.

But it goes deeper than that. Catchers call the game — well, they used to, at least. A good manager knows that he needs the catcher to call the game, since the vantage point from the dugout isn’t good, and since the manager probably doesn’t really know what’s going on out there anyway. Look through the history of baseball, and you’ll realize that it’s always been the catchers who have every opposing hitter memorized, who know where the hot and cold zones are, and who know how to be the psychological coach for the kid on the mound.

In other words — a lot of “pitching” is probably not pitching.

What’s the ratio, then? Who knows. But I sure know it’s not 75%.

The MN Twins are perhaps a data point in this. We have decent pitching this year but have been struggling at the plate and sometimes on defense (16 errors on the season so far). If pitching were 75% of the game, I think we'd be doing much better. We're 7-14 as of last night's loss to the Braves.

It's interesting because James made this same argument in a later Abstract (I think it was 1986 or 1987) about the "scope of occurence."

You make a good point about Ryan facing so many more batters. James' comments don't always hold up in this age of relievers. Kirby Yates faced 237 batters last season, and opponents hit .113 off him. No batter with at least 200 PA hit lower than .150. Similarly, Mason Miller's strikeout percentage was higher than any batter with at least 200 PA, and Chris Martin's walk rate was lower than any batter with at least 100 PA.