How To Write A Great Sports Article

Learning from one of the greatest baseball articles ever

How To Write A Great Sports Article

I shouldn’t be writing this article. I’m not a sports journalist.

However, I really want to share this old article with all of you. I also doubt that any of you have read it. I certainly hadn’t — not until the other day, that is.

There’s an old anthology of good baseball writing that was once popular and has since been forgotten. The series was called The Fireside Book of Baseball, and it was compiled by a delightful literary master named Charles Einstein. Einstein lived up to his namesake, deftly choosing the best of baseball literature and publishing it in a format that we all one thought would stand the test of time.

But, alas, few people care to read books in the digital era. It’s not as sexy and as provocative as browsing for relationship advice on Reddit. And so the four volumes of The Fireside Book of Baseball end up gathering dust on library shelves, and the rest of us go onto social media to complain about how obnoxious Stephen A. Smith is.

I shouldn’t be so negative, of course. I mean, you’re on Substack, of all places. Everybody knows that Substack is the place where literature has finally come to rest — the heaven for those of us who want to read something that wasn’t designed to get as many clicks as humanly possible for the advertising Gods.

And so, since I think there’s likely a good audience here for this, I’ll do my best to do this old work justice.

If you’re keeping score, this comes from pages 35-37 of the first volume of The Firside Book of Baseball, which was published way back in 1956. I was still able to find all four volumes of this collection at my university’s library back in 2002; however, I worry that most institutions of higher learning may have sold their copies off since. You might have good luck on Amazon or eBay.

Preface

Our article comes from The New York World on October 12, 1923. It’s coverage of the second game of that year’s World Series.

This is from back when the World Series really meant something. There was nothing else in the world of American sport quite like the World Series. Sure, there was technically a Stanley Cup in 1923, tied at the time to the winner of the NHA and PCHA championship series — but that was in Canada. Basketball was a college game; football was a college game; soccer was a European game. The World Series was the absolute height of the sporting world in 1923, and was a place where literature, celebrity culture, and good old fashioned blue collar America met every year.

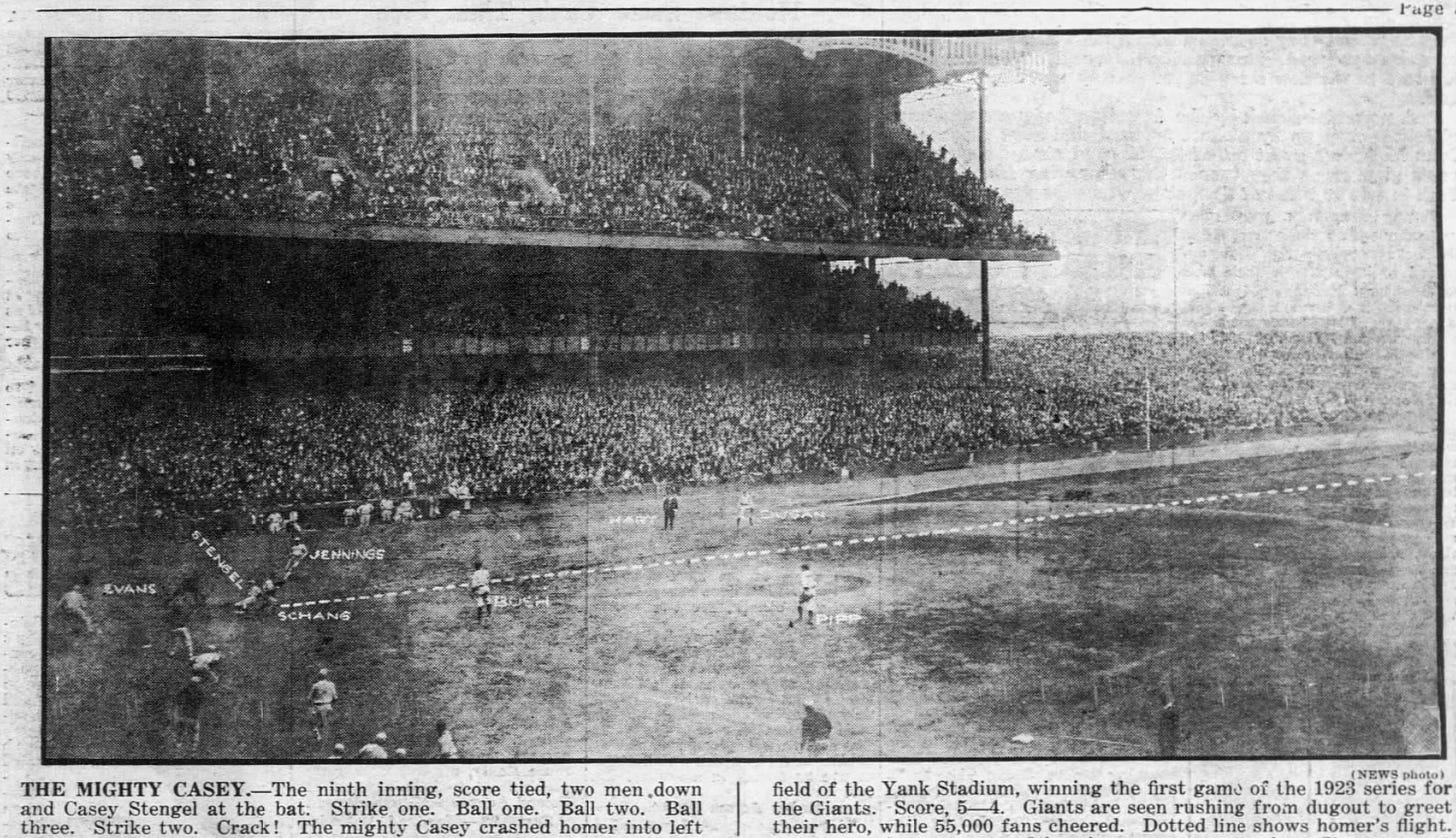

October 11th saw game 2 of the World Series. Game 1 was played at Yankee Stadium; game 2 shifted to the Polo Grounds. This wasn’t because of some stadium defect. It’s because the combatants were the New York Yankees and the New York Giants. Both teams were in the same city, so the powers that were decided that they might as well swap stadiums every single game.

And now let’s hop right into the article — an all-time classic by the long forgotten Heywood Broun:

The Beginning Hook

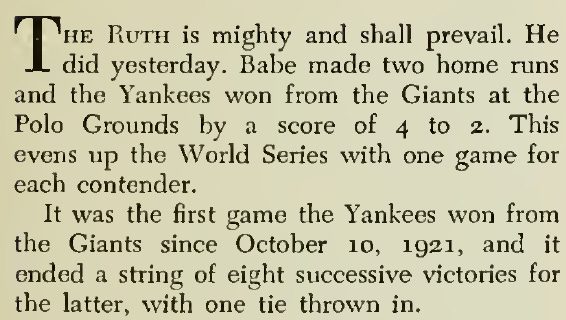

I don’t think I’ve ever read an opening line quite as powerful and as action packed as “The Ruth is mighty and shall prevail.”

Maybe it took Broun hours to think it up. It doesn’t feel that way, though. It feels like it’s something natural, something that you’d say about Michael Jordan after he won his second threepeat, something you might have said about Tom Brady during his long run of dominance.

It’s a simple opening, but makes a profound statement at the end.

You see, the Yankees weren’t the Yankees quite yet. The Giants had won the first game of the 1923 World Series at Yankee Stadium on a 9th inning inside the park home run by Casey Stengel. The mighty, prevailing Ruth had been unsuccessful at knocking one out of the park he built; meanwhile, Stengel managed to score the winning run all by himself without hitting it over the fence.

The Giants had swept the Yankees in the 1922 World Series, and had managed to win the final three games of the 1921 World Series as well.

1921 might as well have been centuries ago. The Yankees and Giants still shared the same stadium back then.

Humor

And then comes the humor, something that we’re missing in modern sports journalism.

The Yankees had lost the first game in large part because of baserunning blunders. Broun doesn’t tell us this; he assumes that we know. Now, if you’re like me you didn’t know this part — but we can always look it up:

And, as any self-respecting sabermetrican will tell you, the nice thing about a home run is that the defense can’t catch it.

The Villain

Nobody wants to make a major sports figure the bad guy these days.

It’s a shame. Readers love the bad guy. In fact, some people like to cheer for the bad guy.

John McGraw, who everybody liked to call Mugsy behind his back, was the original bad guy. And, oh man, how Broun lets us know!

The evil McGraw is set up like a classic Disney movie villain, sneering and jeering at the concept that this hero would even stand a chance against his mighty minions. He is unrepentant, even when faced with evidence of his wrongs:

Motif

Yes, I’m a fan of opera — can you tell?

Braun used a page from Wagner’s book on composing. He reminds us of the same thing time and time again — and it works wonders.

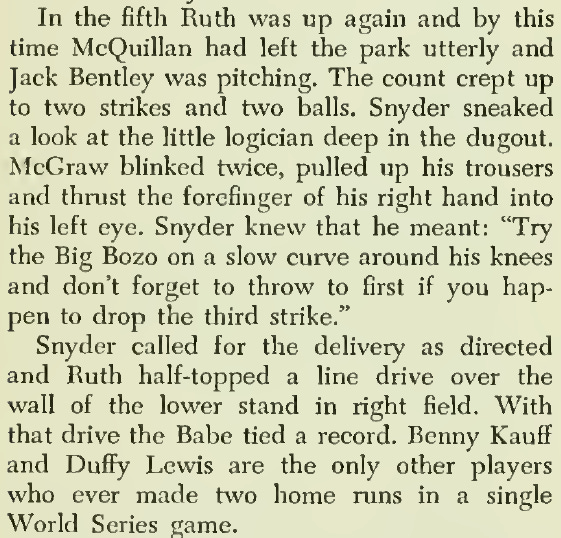

As you’ll notice, the point here isn’t that Ruth hit two home runs. Any moron with a pad of paper can write a story about how Ruth hit one in the 4th inning and another one in the 5th. No — it takes a real master to paint the picture instead of just telling you the facts.

Watch and learn:

We start here with the conclusion. There’s no real suspense. There doesn’t need to be, after all. The reader has already looked at the box score.

The point isn’t that Ruth hit the home run. The point is the picture that is being painted: the catcher pretending to check out the pretty girl in the stands, McGraw scratching his nose defiantly, ordering the pitcher to give Ruth a shoulder high fastball.

And, of course, the result was the reinvention of flight.

But this motif continues:

Do you remember watching the 1991 World Series, when the CBS cameras would catch the Atlanta Braves coaches doing every conceivable motion to send their signs across?

That’s probably what was happening here — though McGraw’s sly and subtle motion of jabbing his finger into his eye was a lot more artful, of course.

And then, of course, comes the best part of the article:

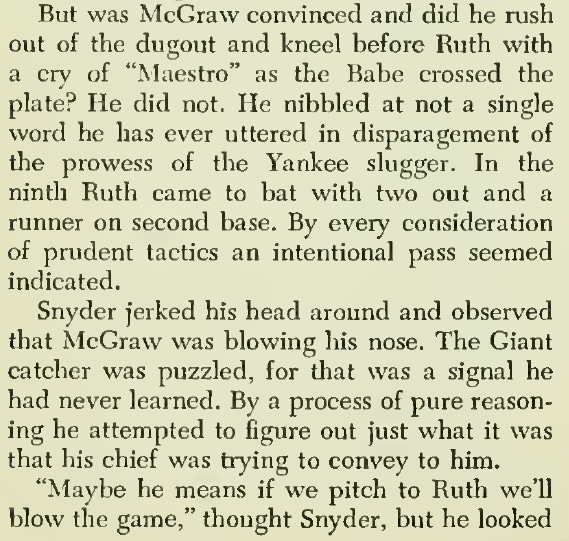

See what I mean by “motif?” You might not remember precisely what inning the Babe hit his long balls, but you’ll never forget that image of McGraw blowing his nose — and then telling the catcher to pitch to the Big Bambino no matter what.

Conclusion

You see — we focus far too much these days on what the players have to say about their performance. We’re too interested in hearing superlatives from the dugout, in getting the same tired answers to the same lousy questions from the men in charge, and in hearing announcers try to come up with new adjectives to tell us just how wonderful everybody is.

Notice how Braun doesn’t bother to make sure that McGraw was really giving the signals. Sure, he may have taken some artistic license — but it worked, didn’t it? Notice how Braun doesn’t even mention that Hugh McQuillan gave up the first home run and Jack Bentley the second. It’s not important. The story is the important thing, and Braun gave us the story, and then did us the favor of cutting out all those pesky details.

The men in Braun’s article are people — well, maybe Ruth wasn’t an average Joe, but everybody else was. We all know someone as arrogant and cocksure as a John McGraw, as puzzled and confused as a Frank Snyder. And we all long to be the Babe Ruth in the story — the mighty warrior who is underestimated and even scoffed at, but who is sure to rise to victory in the end.

This isn’t just a sports article. This is great literature. And we need more writing like this.

Well done, I learned something.

The Fireside Baseball Books are truly Great. I have all 4 original Volumes ⚾️ I am Blessed. Thanks for the Super Article ⚾️