WAR and Replayers

Let me preface this by saying that I am far from a statistical expert. I love baseball statistics, just like any other baseball fan. However, I’m not one of those guys who hangs out on stat-heavy forums, throwing around complicated acronyms and belittling anybody who would dare use a “traditional” baseball statistic.

I’m interested in sabermetrics and in new statistics. However, I also know from experience that those statistics might not be as useful as you might think.

And, honestly, there’s no other way to start this discussion than by talking about the elephant in the room: WAR.

What WAR Actually Is

I took part in a Twitter discussion (yeah, I know, bad idea) a few weeks back. It was some sort of comparison between traditional baseball statistics (batting average, slugging percentage, RBIs, etc) and newer statistics (oWAR, wOBA, cWPA, etc).

Somebody, who I presume is a bit older than me, made a comment akin to “WAR is just computer trickery.”

Now, I take exception to that. You might not like the decades-long attempt to reduce all baseball events to a single number. Honestly, I don’t like it, either. But it’s not just some sort of computer trick.

The theory behind WAR is actually pretty simple. Baseball-Reference does a good job of explaining it here, but I think we can make it even simpler.

You all know who this man is. And, yes, that picture is almost certainly the prototype for the most famous baseball card of all time:

Honus Wagner, as you might already know, had an absolutely incredible season in 1908. It was so incredible, in fact, that it commonly ranks as one of the greatest seasons of all time, especially when using statistics that account for the strength of the league he played in; more on that in a later post.

What you probably didn’t realize is that Wagner was in a contract dispute that prevented him from playing in the first 3 games in 1908. He finally signed after he was offered a reported $10,000 contract:

Now, for the first three games of 1908, the time in which Wagner was still “retired,” the Pirates had to play somebody else at shortstop. Thanks to the game account and boxscore research we’ve had in recent decades, we know that this was Charlie Starr:

And there’s an answer to a trivia question you might not have known existed.

Now, since Wagner was not playing for the Pirates, the Pirates had to put somebody else out there at shortstop. They lost the full offensive and defensive package that Wagner brought to the team, and had to use a lesser player in his place.

WAR is designed to measure this loss. Hence its name: Wins Above Replacement (player).

Now, for WAR to make sense, we’ve got to explain what a “replacement player” actually is. This isn’t an average major league player, for one thing. We’re talking about a player that is easy to obtain — maybe somebody currently in the high minors that can easily be brought up.

Starr is actually not a great example of this, believe it or not. He played with the St. Louis Browns briefly in 1905, handling second base and third base on occasion, but couldn’t hit well enough to stay up. He was with Youngstown in the old Ohio-Pennsylvania league in 1907, where he was actually one of the leading hitters:

We know in hindsight that Starr still couldn’t hit Major League pitching (but, then again, nobody could in 1908). However, from the looks of things, it seems that the Pittsburgh papers were bullish on him:

I could go on (and you’d better believe that I want to!), but I think you get the point. As poorly as Starr played for the Pirates in 1908, he’s doesn’t really fit that theoretical definition of “easily obtained replacement player” that WAR measures players against. If anything, those early Pittsburgh sportswriters were worried about third base, not shortstop.

When we’re talking about WAR, we’re not talking about how much better a given player is than an actual replacement that was on the roster, or in the minor leagues, or anything like that. It’s all completely theoretical.

The theoretical mechanics from this point are actually simple, though the equations are not. We need to have some way to measure what a team is missing without the player we’re looking at, right? We need to have a single unit of measurement that takes everything into account. We need to know just how big of a hit the Pirates will take if Wagner actually does retire and they have to play a replacement level player (again, not specifically Charlie Starr, but a theoretical replacement level player) in his place.

Baseball teams are interested in wins, which is the “w” in WAR. Everything is converted in the end to a theoretical measurement of the number of wins the team would lose if that player were gone. In other words, WAR tells us, in theory, how many wins the Pirates would lose out on if Wagner really did retire in early spring 1908.

It’s hard to measure wins directly. As I understand it, the mechanics of WAR are chiefly concerned with taking raw stats and converting them into runs — both runs created and runs prevented. Those runs are then converted into wins based on the run environment of the league and year.

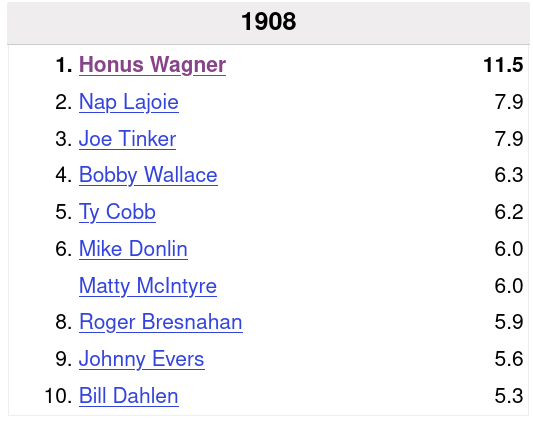

WAR estimates that Honus Wagner was the best position player (non-pitcher) in 1908, and by a long shot:

Wagner’s 1908 season was so remarkable, in fact, that it ranks among the greatest position player (non-pitcher) seasons of all time according to WAR:

Now, note that Wagner didn’t actually earn a certain number of “wins” for the Pirates during 1908. In other words, WAR isn’t a statistic that measures anything tangible. Rather, it gives us a theoretical number that allows us to easily compare players in the same year, or even across different years.

That right there gives you an idea of why it’s controversial, by the way. It’s a complex, theoretical subject — and the more you dig into it, the more you see that it’s sort of a stew of a bunch of different statistical ideas about baseball mixed together.

Is WAR Useful for Replayers?

So what does WAR mean for those of us who care about replays?

Honestly, I don’t think it means much.

Look — I don’t want to disparage the sabermetricans who do this work. I can see WAR’s utility, particularly when it comes to salary negotiations, most valuable player voting, and (to an extent) determining the best players of all time at every position for every single team. It’s not a bunch of fake computer mumbo-jumbo, nor is it so abstract and theoretical to lack any utility.

However, if you’re replaying a season, you probably aren’t asking any of the questions that WAR was designed to answer.

I don’t know how you feel about it, but when I replay a past season I’m not really all that interested in knowing how well a player in my replay compares to a theoretical replacement level player. If I replay 1908, I don’t really care how much better Honus Wagner is in aggregate than a non-existent theoretical replacement.

There are some things I do care about, of course. I care very deeply about making sure that Wagner misses those first three Pirates games, for example. It’s not right for us to stick him in the lineup if he wasn’t really there. That would give the Pirates an advantage that could wind up giving them the pennant in the end.

I also care a lot about Charlie Starr. Anybody can get to know the star player, after all. Players like Starr are often overlooked by researchers. In my opinion, the real joy in replaying a past season is getting to know all of these friends from the past, these guys who were each stars in their own right, many of whom could have been truly great if they just had a break or two go their way.

I want Honus Wagner to play like Honus Wagner, of course. But he doesn’t have to play exactly like Honus Wagner. Within the realm of statistical probability, I’m fine with deviation from his .354 batting average, for example.

The same is true of Starr. He hit .186 in his 76 plate appearances in 1908, managing only 2 extra-base hits (both doubles). He also stole 6 bases, which is impressive given how infrequently he was on base — and I will note that the Pittsburgh papers mentioned his speed (though one paper claimed he had 75 stolen bases with Youngstown, which I think came from a misreading of the Reach Guide).

I want the players to play like themselves. If Wagner comes up to the plate, I want to see Honus Wagner up at the plate, making the National League pitchers quiver in their boots. If Starr comes up to the plate and starts hitting like Wagner on occasion, I might not pay much attention to it. However, if Starr starts hitting like Wagner in the long run, I’m going to start questioning the accuracy of the game engine I’m using.

Note, though, that none of the things I care about match up with what WAR can tell me. WAR will tell me that Wagner contributed 11.4 theoretical wins to the Pirates, and that Starr contributed 0.3. But that doesn’t tell me anything. I already knew that Wagner was the better player, after all, and the scale itself is meaningless.

If I complete a 1908 season replay and Wagner winds up with a WAR of 12, or of 11, or of 13 or something else, I’m not really going to care. I’d notice that he had a better offensive season, which is the sort of fluctuation that is fairly normal in replay projects.

I’d probably care a bit more if Starr managed a WAR of 1, and would absolutely care if he had a WAR of anything more than that. But, honestly, I’d be able to tell something was off without going to the trouble of computing all of the individual run creation and prevention components.

You might feel differently — but, for me, the real joy and magic of baseball and replaying comes in the stories, not in the stats alone. And WAR just doesn’t tell good stories.