Jimmy Shevlin

Every once in a while I run into a player about whom nothing is known.

This goes beyond the “underrated” players that are a staple of the @notgaetti Twitter account. We’re talking about players about whom we know basically nothing.

Jimmy Shevlin is one of them.

Don’t believe me? Here is his Baseball Reference Bullpen page:

That means that all we really know about him comes from his Baseball Reference stats:

I mean, there’s really not much. He played a little bit for Detroit in 1930, made it back home to Cincinnati in 1932, and left the major leagues after only 53 games.

Who Was Shevlin?

The story of Shevlin is sort of remarkable, actually. Jimmy was a 20 year old in 1930 who was tearing the cover off the ball for Holy Cross:

Shevlin’s batting accomplishments in college were so impressive that he started fielding offers from major league teams right away.

It was only a few weeks later that Shevlin signed for the Tigers:

Shevlin seemed to be one of those early big contract signings, the sort of player that a team in desperate need of help would throw a ton of money at, hoping that things would go well:

Needless to say, Shevlin’s signing in 1930 was a pretty big deal. The news went out over the wire services, and just about every newspaper in the United States had at least a small blurb about the Holy Cross phenom who just signed the big contract with Detroit.

Shevlin In 1930

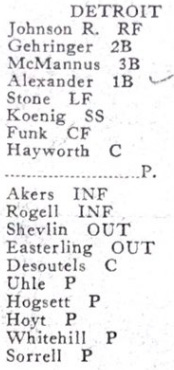

I know what Bucky Harris is reported as saying above. If he really said that, he was kind of fibbing.

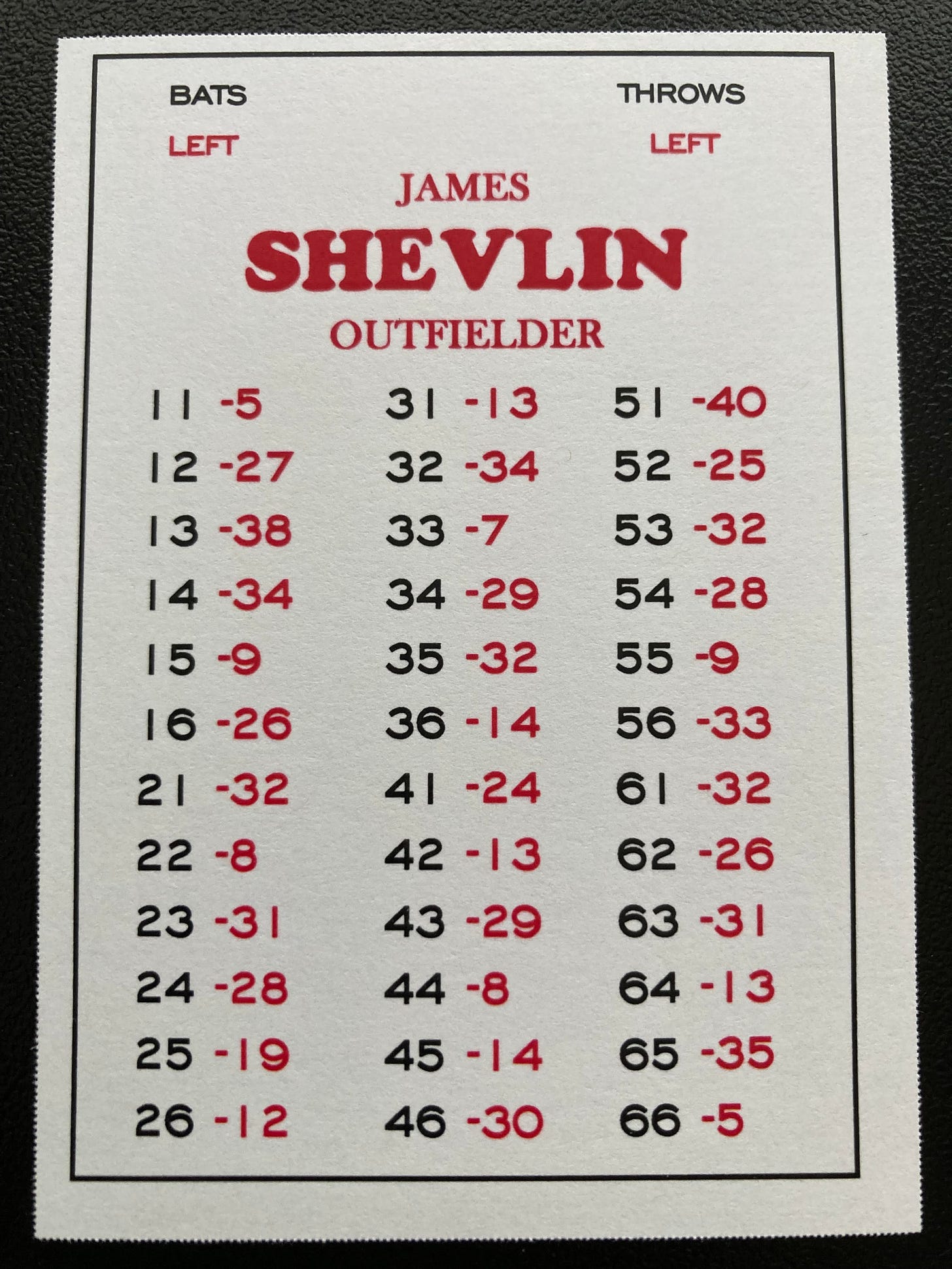

The Tigers had 27-year-old Dale Alexander at first base in 1930. Alexander started every single game, relegating Jimmy to a late-inning replacement role:

If you’re curious, those times when Shevlin is listed as appearing in inning “0” are games for which we don’t have full play-by-play records.

Shevlin made 0 defensive starts and only occasionally stayed in the game as a first baseman, as you can see from our (admittedly incomplete) defensive logs:

Note in particular that Shevlin only played first base.

Now, there’s a reason why Jimmy didn’t play more often. His first pinch running appearance ended in a disaster that was reported on in sports pages all over the country:

And, yeah, the game was a little bit rougher in those days.

Shevlin did get a chance or two afterwards:

Sadly, though, the Jimmy Shevlin experiment at Detroit would not last long. By spring 1931, Jimmy was with Toronto:

We’ll leave our research into Shevlin here for the time being.

Van Beek’s Error

Why am I telling you all this?

Well, it just so happens that Clifford Van Beek made a mistake with Shevlin.

If you’ve been paying attention, you’ve seen that Shevlin was always listed as a first baseman. He never played any other position — not to my knowledge, at least.

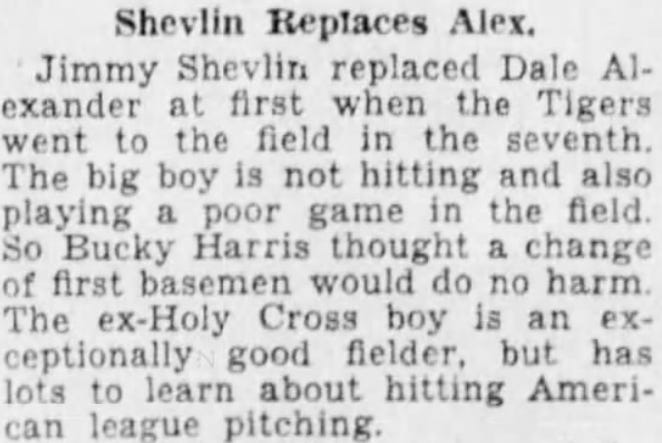

However, this is what his National Pastime card looks like:

It’s not just his card that says he’s an outfielder. The Detroit roster has him listed as an outfielder, too:

This tells us a few things about how Van Beek created his game.

Van Beek Did Not Use The 1931 Baseball Guides

The first thing this point tells us is that Clifford Van Beek did not use the 1931 baseball guides.

I know this seems like a stretch. However, it becomes readily apparent as soon as you look at the fielding page.

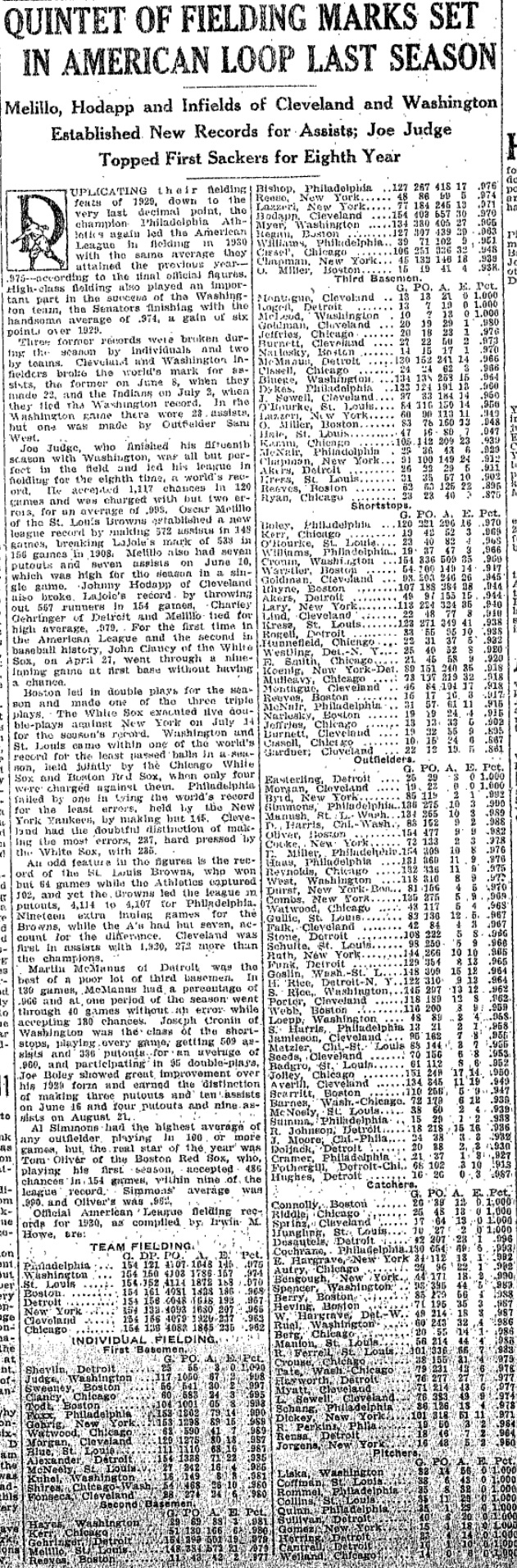

Had he used either the 1931 Reach or Spalding Guide to create his came, Clifford Van Beek would presumably have started with the list of hitters arranged by batting average — which, at the time, was simply the “scientific” way that hitters were listed. That page looks like this:

Van Beek would have had to choose the players he wanted to investigate, and then turn over to the fielding pages to learn what hand they threw with and what position they played:

As you can see, Shevlin is the first name listed.

Clifford Van Beek simply could not have ignored his name. I don’t believe it is possible for Van Beek to use this method to create his player cards without discovering that Shevlin was a first baseman.

In fact, I don’t believe that Van Beek even used the fielding stats printed in The Sporting News. As you can see here, Shevlin was listed first in those stats as well, thanks to that 1.000 fielding percentage:

Remember that these stats come from the very same issue of The Sporting News that includes that famous National Pastime advertisement.

I’m convinced that Van Beek’s cards were already printed and ready to sell by the time this list came out. And I doubt he even bothered to look at this page to discover his Shevlin mistake.

What Did Van Beek Use?

The truth is that I’m not entirely certain what Van Beek used.

I do know, though, that he should have seen that Shevlin was a first baseman in his boxscore collecting, as he was going through each day’s games.

Here’s a Chicago Daily Tribune boxscore from a game that Shevlin played in:

I was curious to see whether The Sporting News listed Shevlin as a first baseman or as a pinch hitter for this game. This is what I found:

Even if we suspect that Van Beek was only using boxscores from September to piece together his game, he couldn’t have missed this one:

It’s theoretically possible that Shevlin was listed as an outfielder to provide balance for the Tigers. Looking at the breakdown of teams indicates that this might be a possibility:

The Tigers would have 7 infielders if Shevlin was listed correctly, along with 4 outfielders. Other teams also had 4 outfielders, though both of those teams (the Phillies and Senators) had a third catcher.

Pinky Hargrave would have been an obvious candidate for the third catcher spot — but he ended the season with the Washington Senators. Tony Rensa comes up next on the list — but he ended the season with the Philadelphia Phillies. That leaves only Hughie Wise as a third catcher — and he played in only 2 games, meaning that Van Beek probably couldn’t find any statistics for him if he tried.

Van Beek’s best option would have probably been to call benchwarmer Billy Rogell an outfielder, since he had a single appearance in left field in 1930. We can only speculate why that didn’t happen.

One other note: Shevlin’s Holy Cross classmate Gene Desautels also made it onto Detroit’s roster — as a catcher, no less. Desautels had a much more successful major league career, lasting 13 seasons.