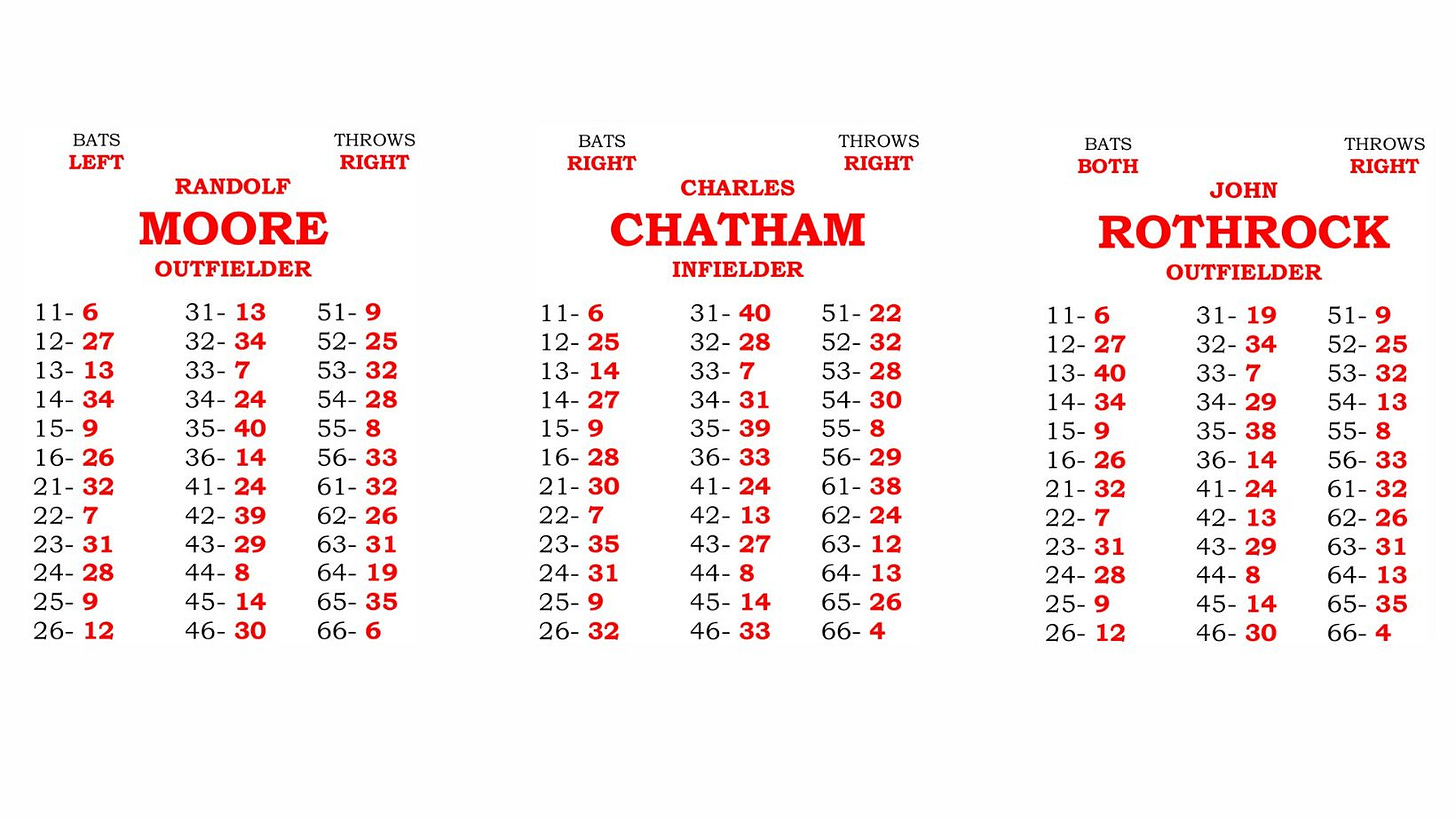

Moore, Chatham, and Rothrock

There are more patterns in National Pastime than you think.

We’ve tried looking for them, but have come up relatively empty handed so far. We do know a few things, of course. We know that pitchers have a monopoly on 23s, for example. We know that 2 and 3 were both very rare play results from the start. We also know that 41 is a mystery: it’s not quite clear why it even exists.

Now let’s have some real fun. Let’s look at the outs.

Platooning

I’ve thought for a while about the best way to introduce this topic. However, instead of trying to come up with something creative, I’m just going to come out with it.

Clifford Van Beek created and used default cards to handle out number distribution in National Pastime.

Now, this is the sort of thing you’ll never come up with if you look at the cards alone. You’ve got to create a chart to see what he’s doing. And you also need to know his biggest secret.

There were actually two different model cards that Van Beek used to distribute outs: one for left handed batters, and another for right handed batters.

This sounds odd, right? Was this supposed to be some kind of split system? Why differentiate out distribution based on the handedness of the batter?

I don’t know why, but I do know for a fact that he did this. Just take a look at the charts.

First off, this is the play result distribution for left handed batters:

94 players are designated as left handed batters. Therefore, when 93 of them receive a “32” result at dice roll number 21, you know it’s significant.

Now let’s look at right handed batters:

There are 177 right handed batters in National Pastime. When you realize that 175 of them received a “24” at dice roll 41, you know it’s significant.

Finally, there are a few batters listed as batting “both:”

Only 18 hitters received the “both” batting designation. As you can see, 17 of those received a “35” on dice roll 65.

We can take these three general distributions and come up with an approximation of the model cards Clifford Van Beek used to distribute outs:

As you can see, the “Both” batters are issued left handed batter cards for the most part. The key identifier is across the top: 12-27, 32-34, and 52-25 means it’s a lefty or switch hitter, whereas 12-25, 32-28, and 52-32 means it’s a right handed hitter.

This doesn’t work 100% of the time, by the way. There are some cards that have incorrect batting handedness, believe it or not. There are also cards that contain other errors, which we’ll get to a bit later.

However, this holds true so often that there’s no doubt in my mind that this is how Clifford Van Beek did it.

The 13

The biggest exception to this rule is play result number 13.

13 can show up just about anywhere. It’s easier to list the dice rolls that never contain play result number 13:

11

22

33

44

55

66

All other numbers, including numbers you would think would be “hit” numbers, contain a 13 on at least one card.

Now, don’t freak out too much about that. As you’ll remember from previous installments, most of those 13s come on pitchers cards. There aren’t a bunch of non-pitchers who were unlucky enough to get a 13 on dice roll 15, for example.

We’ll take a closer look at the 13 in a future post.

Samples

Below are a few cards that represent the patterns, more or less.

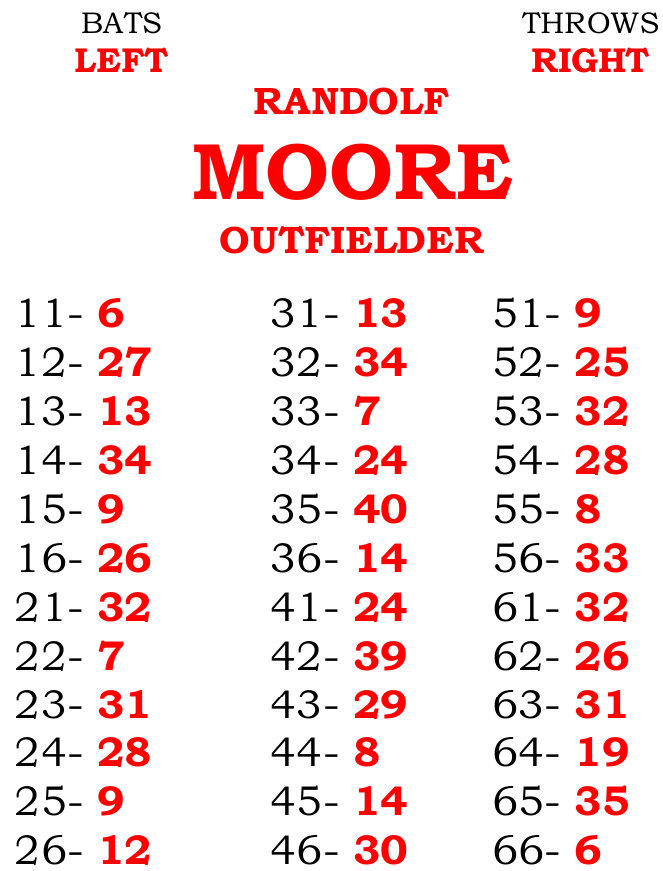

First, representing the left handed batters, here is Randolf Moore of the Boston Braves:

The exception here is a “24” on 34, instead of a “29.” This might be a typo, or it might not — we’ll have to look deeper into double play roll distribution to find out.

For right handed batters, here is Charles Chatham, also of the Boston Braves:

The exception here is the “24” on dice roll 62, instead of the expected “34.”

And, finally, representing the switch hitters, here is John Rothrock of the Boston Red Sox:

That “13” on 54 (in place of a 28) is the only result that breaks the pattern.

We’ll take a closer look at these patterns and why we think Clifford Van Beek would break them in a future post. What’s clear here, though, is that they weren’t frequently broken.