Moving Forward with National Pastime

We’ve been through a bit of preliminary work on National Pastime. We’ve looked at some of Clifford Van Beek’s predecessors and likely sources for inspiration. We’ve also looked at when the game was likely published (I maintain that it likely came out in December 1930, much earlier than we first thought), and we’ve looked into the rosters and provided lineups.

There’s a lot more that we can do from here.

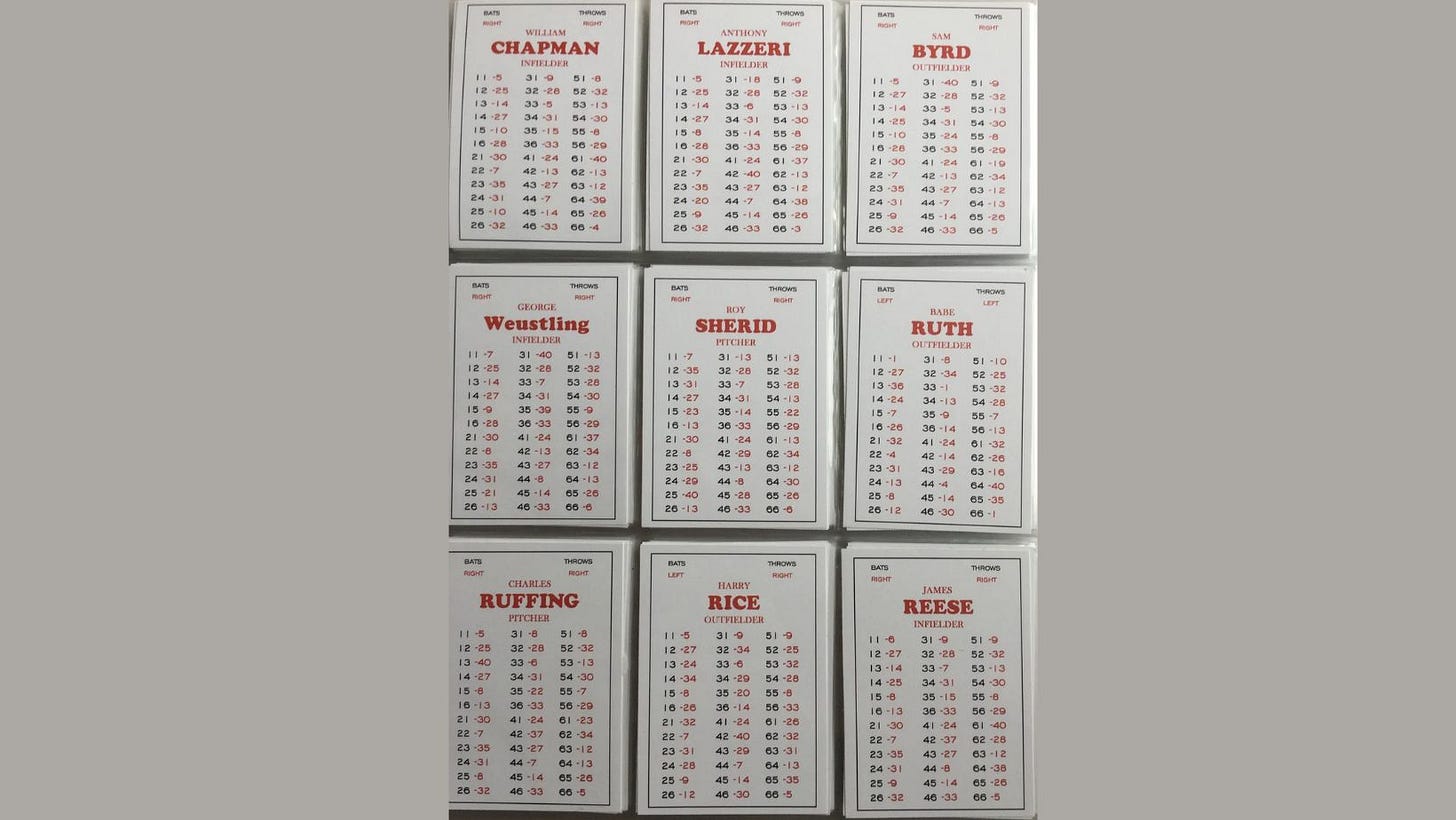

I think the next logical step will be to take a very close look at the National Pastime boards. It’s difficult to understand and evaluate the cards without looking at the boards and asking ourselves a few interesting questions about why things are set up the way they are.

The cards themselves will come afterwards.

The truth is, though, that people much smarter and older than me have already taken a deep look at the cards themselves. Questions of expected statistical output given the provided playing boards are really mathematical problems that can be solved. In fact, since we have the boards, the game engine itself is wide open and lends itself well to analysis and study.

Anyway, we’re going to go slowly through these steps and see where we wind up. As always, if I say something wrong (which I almost certainly will), please let me know. This is not designed to make me look like an expert on the subject; rather, my hope is that we can get a more robust discussion flowing.

Who Cares?

The obvious question here is “who cares?”

It is a good question, actually. National Pastime came out in late 1930, and likely disappeared completely from the market when Clifford Van Beek was successfully sued by his printer in early 1932.

Really, this board game would have been unknown by any but the most dedicated dice baseball historians had it not been for J. Richard Seitz. Seitz took National Pastime, turned it into a draft league with his friends, and eventually come up with certain innovations and modifications that transformed the game into APBA.

APBA’s game engine and history is also well known, and I don’t think it’s likely that I’m going to come up with any new or surprising insights. We will go into detail about the beginnings of APBA and its development — well, at least through the stuff that is publicly available and that we can figure out from the boards and the cards.

But all of that is in the far off future.

Surprising as it may seem, there are really interesting lessons that Clifford Van Beek teaches us about business development. Van Beek had an excellent product, one that was obviously more advanced than anything else on the market at the time. Van Beek’s timing was poor, however: his release schedule ran smack into the worst of the Great Depression, and his attempt to market the game at Christmas time betrayed a lack of insight into the buying habits of his potential customers. The story of National Pastime is the story of good creation and poor marketing: a game that was ahead of its time, but a game that hit the market with no real plan.

I don’t know if that insight is good enough to compel us to be interested in the game itself. At the very least, though, National Pastime remains an understudied part of the history of baseball simulation — a place few have bothered going, but a place that is worth visiting in the end.

As always, you can find my ongoing series on National Pastime here:

National Pastime

This is not a blog about the old National Pastime board game. Initially, I wanted to write a few posts about the connection between Clifford Van Beek’s extremely obscure 1930 creation and J. Richard Seitz’ 1951 APBA baseball game. However, as I started to research things, I realized that there was a huge story that had never been told — one that seems to …

And, if you enjoyed this article or this series, why not refer it to somebody else? It’s free, after all!