This post includes affiliate links. If you use these links to purchase something, this blog may earn a commission. Thank you.

Mugsy

I’ll never understand why John McGraw’s biographers ignore his 1900 season.

Okay — “ignore” might be a strong word here. But it’s kind of hard to feel otherwise.

In what is undoubtedly the best biography of McGraw, Charles Alexander devotes only 4 pages to the 1900 season, most of which is designed to set up McGraw’s unholy baseball union with Ban Johnson. McGraw’s autobiography includes only 2 pages about the 1900 season, with surprisingly little information.

Wikipedia almost completely skips the 1900 season, giving it a single sentence. And McGraw’s SABR biography is worst of all, only mentioning the contract that he signed.

This is absolutely bizarre. McGraw was clearly one of the best players in the 1900 National League, and was arguably the most visible and important figure in baseball that season. He was an attention magnet in the press, a cross between Pete Rose and Ty Cobb in terms of how much opposing fans hated him, and closer to Babe Ruth in terms of raw offensive productivity. And his actions off the field proved pivotal for the development of the game.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let me back up a bit.

1899

In 1899, I’d rather have John McGraw on my team than Honus Wagner.

That sounds crazy, but I really mean it. Both player were essentially the same age: Wagner was 25, McGraw was 26. McGraw had been in the major leagues since he joined the original Orioles (then in the American Association) in 1891 at age 18. Wagner was in his third year with Louisville, a National League team that is completely forgotten these days.

These are Wagner’s 1899 offensive stats:

Wagner clearly had a great year, right? He had a .341/.395/.501 batting line with 7 home runs in 148 games.

Well, here’s what McGraw did:

That’s right. In 117 games, McGraw put up a .391/.547(!)/.446 line, leading the National League in runs scored and walks, and putting together the most impressive offensive season in the entire league.

And, if that wasn’t enough, John McGraw was also manager of the Baltimore Orioles that year, leading a team that had been decimated by owner Harry von der Horst, who had recently purchased the Brooklyn team. Horst quietly moved all the effective Oriole players (and manager Ned Hanlon) over to Brooklyn, where they formed that team of bullies that I complained about a few days ago.

Now, you probably have realized by now that I’m not the biggest fan of WAR. However, I should note that John McGraw is tied for the lead in WAR among non-position players in 1899, according to the latest Baseball Reference calculation method:

I’ve included some of the extra fields to show those who might be interested in other rankings similar to WAR. McGraw actually has more “runs above replacement level” than Ed Delahanty, who I suspect received a boost by the WAR formula due to his position.

At any rate, McGraw was simply awesome in 1899. There’s no question about that.

Holdout

After the National League dropped 4 franchises before the 1900 season, McGraw refused to play for Brooklyn. He wound up sold to St. Louis. Here is how he describes it in his autobiography:

Baseball Reference cites the sales figure at $19,000, noting that it included Wilbert Robinson (famous for his later exploits as Brooklyn manager) and Bill Keister.

McGraw didn’t want to leave Baltimore, and simply didn’t sign up. He became a contract holdout, and, in retrospect, probably should have been one of the most famous contract holdouts in the history of major league baseball.

You can see the skepticism all over the St. Louis papers when you look at what they said about this signing. There were articles like this one:

McGraw himself loudly (and very publicly) announced his intention to hold out:

This was no empty threat. McGraw didn’t sign for St. Louis before opening day.

The St. Louis newspapers still reflected a somewhat cautious optimism that both Robinson and McGraw would eventually come around. We tend to forget this, but Cy Young was the leading pitcher on St. Louis that year. With the addition of the man who was arguably the greatest hitter in baseball, well, you can’t blame the reporters for being a bit optimistic:

That might not be the most scientific method in the world, but it’s still pretty impressive, especially when you realize that calculators weren’t exactly a thing in 1900.

Tellingly, though, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch’s opening day poem featured no reference whatsoever to the two new acquisitions from Baltimore:

And, yes, I wanted to include this because of how cool that poem is.

The Deal

McGraw and Robinson held out until early May, staying out of the game for nearly a month.

This was no acquiescence on the part of McGraw, by the way. Charles Alexander makes that extremely clear:

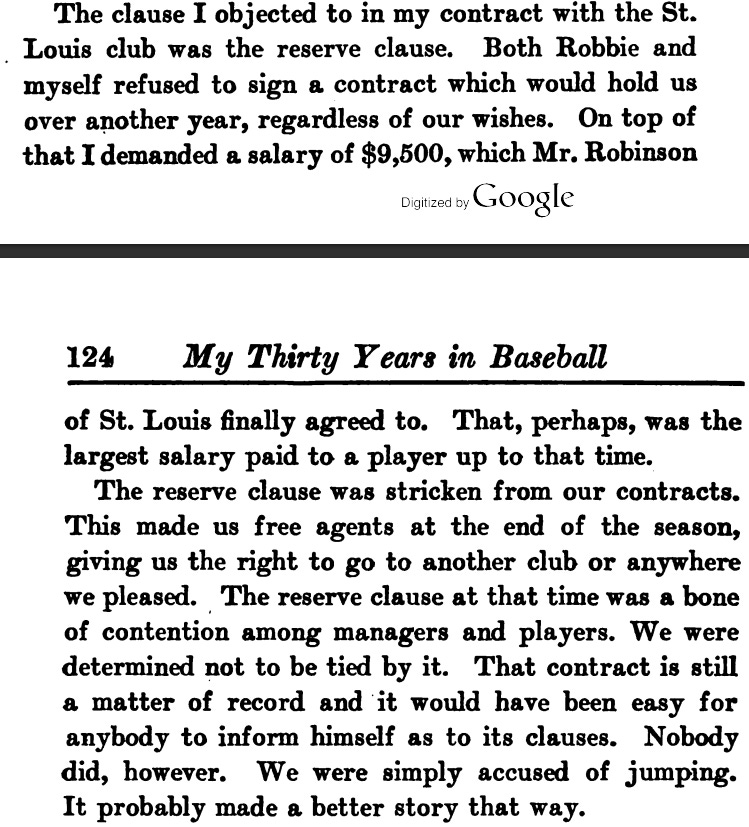

Now, I want to emphasize this point, since nobody else seems to think this is important.

John McGraw being offered a $10,000 contract in 1900 with no reserve clause is absolutely amazing.

I’d argue that it wasn’t just “unheard-of.” It was fantastic beyond belief. With the American League growing in stature and constant rumors of the creation of an American Association, this contract clause guaranteed that McGraw (and the aging Robinson) could go wherever he pleased as a free agent.

And, if you trust those newspaper articles I quoted above, McGraw was also making double his salary in Baltimore.

That should give you an idea of just how great a player John McGraw was.

This is how McGraw describes that contract:

Now, it’s never good historical practice to claim to know exactly what people were thinking at such-and-such time when such-and-such happened. However, I am absolutely convince that McGraw knew exactly what he was doing. He had the upper hand in these negotiations because of his incredible value as a player, and he also likely guessed that he could play multiple major leagues off each other once his free agency was officially granted.

It was simply a brilliant move for a brilliant (yet controversial) baseball mind.

1900

Now, after all of that commotion, you can’t blame McGraw for not having the best season in 1900.

He played in only 99 games (out of 140 - remember that this was before the 154 game schedule, which didn’t start until 1904) due to injuries and other ailments. And yet, despite all of his misgivings and upset feelings, he still put up a .344/.505/.416 line with an incredible display of offensive productivity.

McGraw didn’t beat out Honus Wagner in overall value that year. However, 5.3 WAR is actually really impressive when you consider the fact that he only played in 99 games:

Once again, you can make a strong argument that McGraw was the best player in the entire National League in 1900, after accounting for time lost due to his holdout and ailments.

But there was more to McGraw’s 1900 season than just his success on the field.

Manager

It’s not clear if McGraw actually became the St. Louis manager in 1900 or not.

There certainly were people who thought he should have become manager. It’s not hard to find articles like this:

Rumors that McGraw was going to take over the St. Louis managerial post began as soon as he signed.

It’s not hard to see why. St. Louis was in 7th place on July 29th, when this article came out. Though McGraw was leading the league in batting average at the time (a hair under .400, according to contemporary newspaper accounts), the St. Louis offense simply couldn’t find a spark.

There may have been some cohesion issues, as Alexander hints:

Now, I’m not a professional historian, and am absolutely not in a position to challenge Mr. Alexander’s conclusions. However, I have a hard time believing that McGraw was really an outcast on this squad. He was clearly the best player on the team, and also had managerial experience himself. He must have known how important it was for a team leader to follow.

I’ve also not seen any newspaper rumors or reporting that confirm Alexander’s assertion. To the contrary, The Enquirer in Cincinnati, which was by far the best newspaper in the country for baseball rumors and gossip, printed tidbits like these:

By the way, the great irony here is that Patsy Tebeau resigned as St. Louis manager on the very day that was printed.

And this is where things get confusing.

Some papers reported that McGraw became St. Louis manager right away:

However, if you look at the official record, you’ll see Louis Heilbroner listed as the second 1900 St. Louis manager.

And that’s where this becomes confusing.

Heilbroner was employed as some sort of secretary in the St. Louis organization at the time. He had no major league baseball playing experience, and was apparently officially named as “business manager” after Tebeau resigned.

McGraw himself flatly denied that he accepted to become team manager — a claim that has become accepted as truth as time has elapsed. I assume that interviews like this played a role:

McGraw further denied becoming St. Louis manager in his autobiography:

But, of course, this makes absolutely no sense.

McGraw was captain of the team. By all contemporary accounts I have read, he quickly emerged as a team leader — not surprising for a man who was arguably the best player in baseball at the time, and who had prior managerial experience. To bypass him in this situation and name an inexperienced secretary as team manager makes absolutely no sense.

I apologize for not finding good sources for this claim (many of the old 1900 newspapers are not searchable, and quite a few are illegible), but I have seen rumors in the old papers that McGraw was scheming to have Tebeau ousted as manager. My opinion is that McGraw denied taking over managerial duties to quell those rumors — likely to try to fight against the common public perception that he was a selfish man who always wanted to be in charge.

Even Alexander hints that McGraw was actually managing the team:

And the contemporary papers certainly give you that impression. Here’s a snippet from a front-page article about a mid-September series in Pittsburgh, with the pennant still theoretically within reach for the Pirates:

Notice that St. Louis is described as “Mugsy McGraw’s St. Louis gang” in that second paragraph, which was the customary way to refer to the team’s manager in those days. There is absolutely no reference to Heilbronner in this article, nor is there anything about him anywhere in the sports page.

You can judge for yourself. In my opinion, though, McGraw should be recognized as manager of St. Louis during the second part of the 1900 season.

Remarkable

Now, think for a minute about what just happened here.

John McGraw was likely the best player in all of baseball in 1899. He insisted on staying in Baltimore, and started flirting with the idea of joining (or even forming) a rival league after he was sold to St. Louis.

McGraw was manager of that 1899 Baltimore team, and did well with a significantly disadvantaged roster and an owner who had every intention to dismantle the team.

John decided to hold out at the start of the 1900 season. Not only was his holdout successful, but McGraw came out of that presumably earning more money than any player had in baseball history, taking in the incredible sum of $10,000 a year.

And don’t forget that his contract didn’t have a reserve clause, which is absolutely bonkers. McGraw’s holdout was probably the most successful contract holdout in the history of the game.

John was made captain of the St. Louis team when he finally joined, and proceeded to have a superb season despite injuries and missing the first month.

And, to top it all off, he wound up managing the team at the end of the season.

That’s right: John McGraw went from early season holdout to managing the entire team by the end.

I’m still baffled as to why nobody pays attention to this story. It’s nothing short of remarkable.