History Lesson

I’ve been thinking of writing this post for months now.

Actually, I’ve been thinking for a few years that somebody should address some of these issues. It wasn’t until recently that I decided that this “somebody” should be me.

There’s a lot of misinformation out there. Some people believe that J. Richard Seitz was the actual inventor of the original APBA boards, for example. Others believe that the first baseball game centered around recreating real life statistics was the old All-Star Baseball spinner game. Take this, for example:

Now, don’t log on to Board Game Geek and tell Mr. Patterson that he’s wrong. Somebody has already done that. Just be aware that most people in the world of board game simulations credit either APBA or All-Star Baseball with being the first of its kind.

They’re simply wrong.

Now — this is not a history blog. Our focus here is on baseball simulations, not necessarily on the history of these games. I’m not interested in writing a comprehensive history of baseball board games.

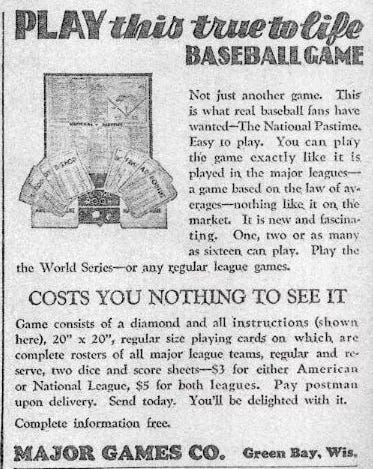

I am interested in telling you about the history behind Skeetersoft. I can’t tell you that history, though, without starting with APBA. And the truth is that no history of APBA is complete (or accurate) without talking about the game that started it all: National Pastime.

Clifford Van Beek

National pastime was invented by an orphan named Clifford Van Beek.

There are numerous ways to tell his story. I think the best way to understand it, though, is to simply quote what has already been written.

This description comes from an old copy of Strat-O-Matic Review that was graciously scanned and uploaded by somebody a few years back:

Van Beek’s game apparently entered development around the time he was 14 years old. According to this article, Van Beek’s board game was in development starting sometime around 1917.

Now, there have been numerous rumors posted on numerous message boards over the years. Some have claimed that Van Beek created National Pastime to while away his days while at an orphanage. I tend to believe that he was with his grandparents in Green Bay, Wisconsin — precisely because there is a lot of evidence that Van Beek spent his entire life in Green Bay.

Others have surmised that Van Beek may have taken frequent trips to Chicago to watch either the Cubs or the White Sox play in the late 1910s. Again, all of this is speculation: we just don’t know for sure.

There are some things that we know for sure about Van Beek, though. For one, we know that he applied for a patent for his baseball game in 1923. Here’s the proof.

The shots of the game boards on the first page of the patent will seem familiar to you if you are used to APBA games. Though the descriptions are a bit more sparse than the ones J. Richard Seitz would use for the APBA game boards, the numbers and play results correspond almost exactly to what APBA would later employ.

And note, of course, that this patent was filed on September 17, 1923. Van Beek was barely 20 years old when he submitted this application.

But I’m getting a little bit ahead of myself.

The Game

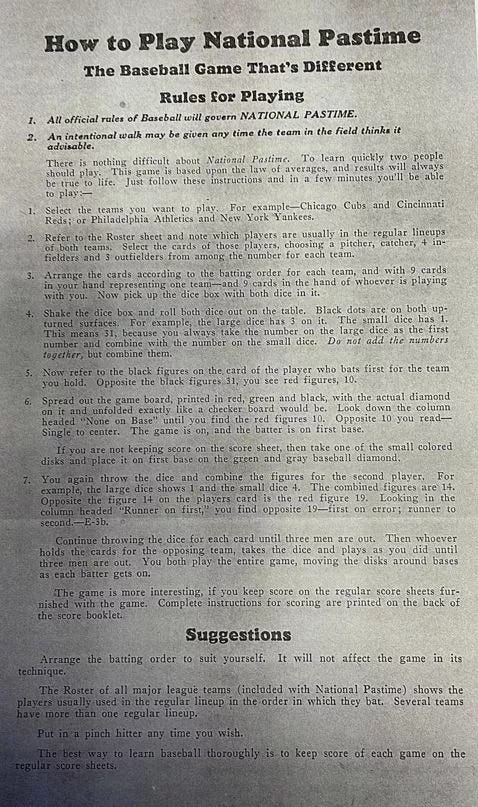

National Pastime is a simple game.

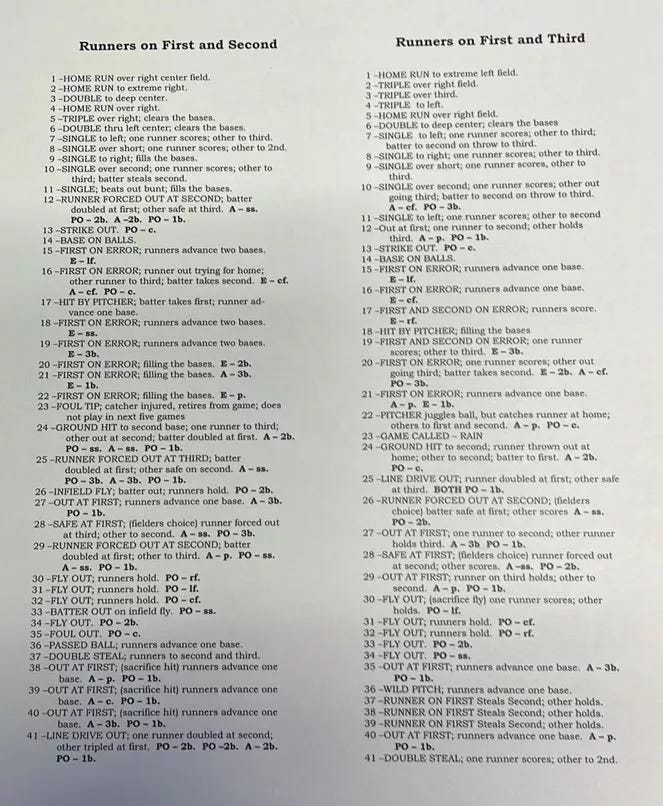

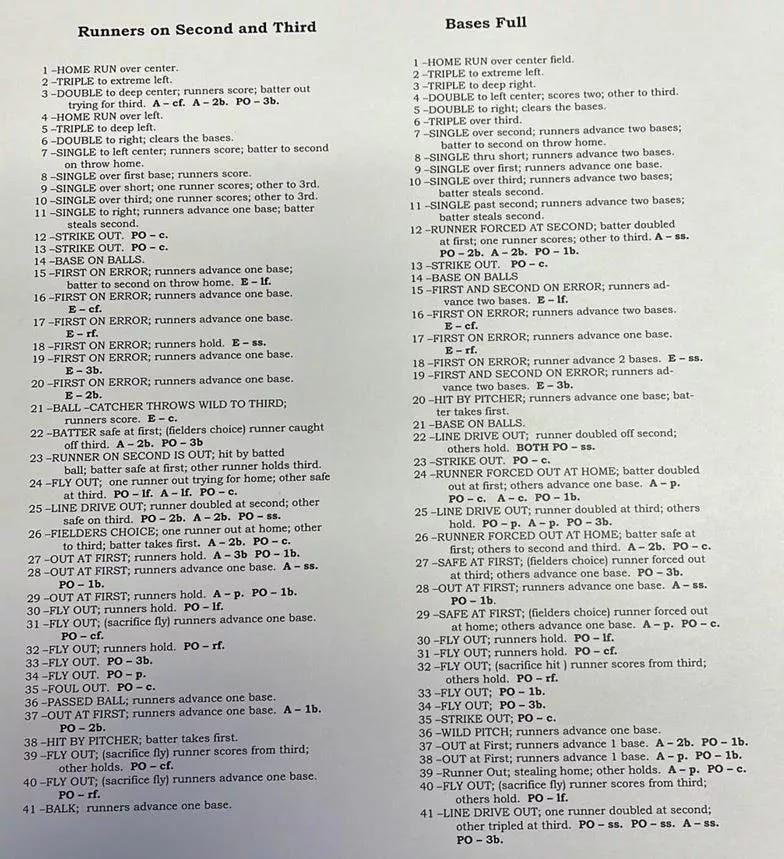

Van Beek created a series of charts — 8 in all. These correspond with the 8 on-base situations that are possible in baseball:

Bases empty

Runner on 1st

Runner on 2nd

Runner on 3rd

Runners on 1st and 2nd

Runners on 2nd and 3rd

Bases full

I’ve included photos of the original play charts throughout the rest of this section to illustrate what it looked like. These are reprints from Sports Game Publishing, an imprint that I believe was once owned by Francis Rose and is now defunct. Even the reprints of this game are hard to come by. I’ve taken these images from Board Game Geek.

Each of these charts contain 41 results, which correspond to situation-specific baseball results, as you can see.

Now, there has been some controversy over time as to whether these charts were created specifically for the deadball era. The chief controversy involves the fact that 2 of the play results (#2 and #3) are chiefly triple results, 3 more (#4, #5, and #6) are for doubles, and only 1 (#1) seems to be home run specific.

That’s why I post the charts here. If you glance at them quickly, you’ll see that this criticism simply isn’t valid. Aside from play result #1, each of the other hit results differ slightly in terms of offensive value depending on the base situation. For example, result #2 in National Pastime is a home run with runners on first and second, and yet is a triple at all other times.

This gives you a little bit of insight into the genius that Clifford Van Beek possessed. National Pastime’s boards were never designed to recreate a certain era of baseball. Instead, they were designed to give the game designer a certain amount of statistical accuracy without requiring an overly complex game engine.

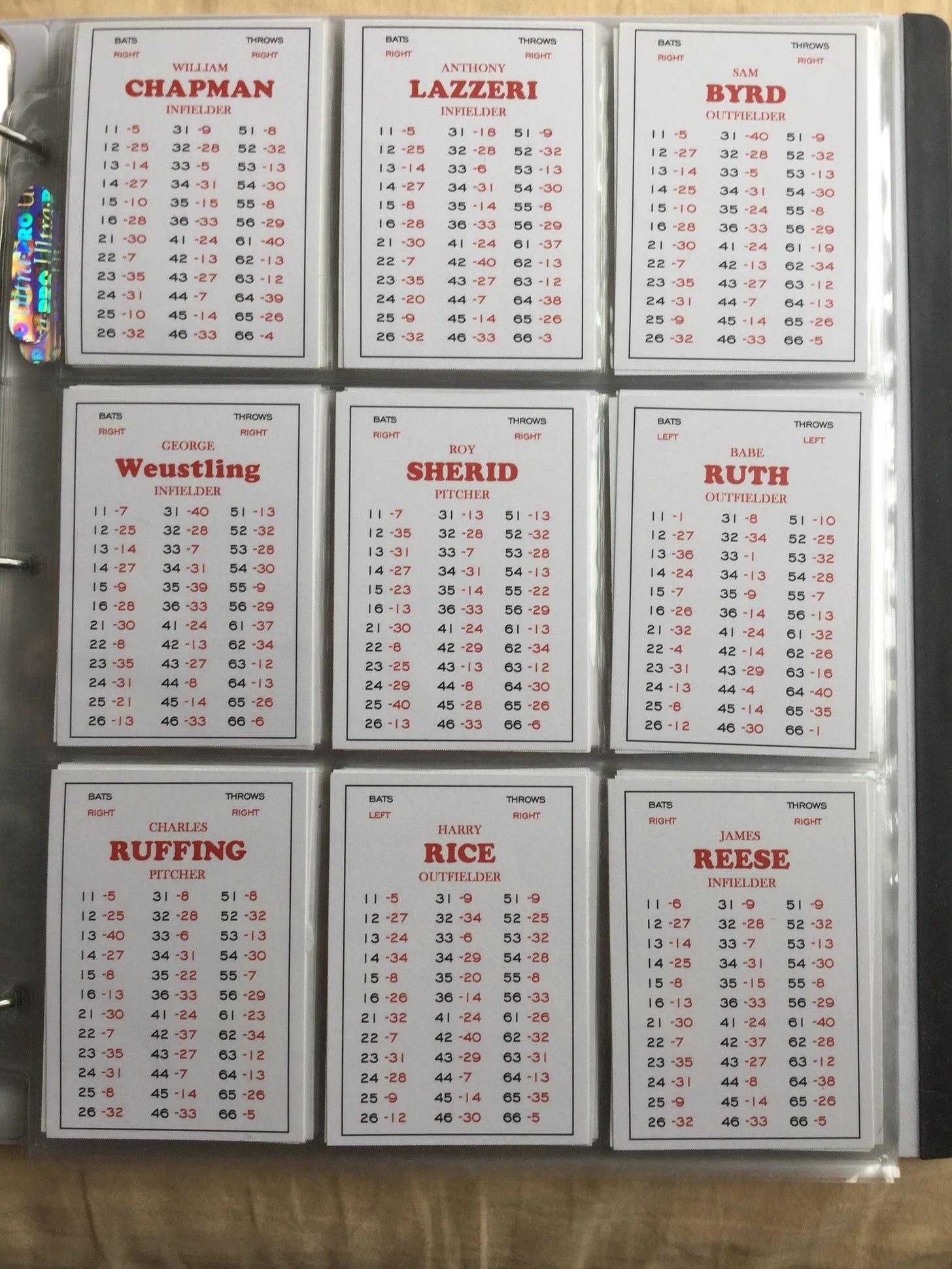

The Cards

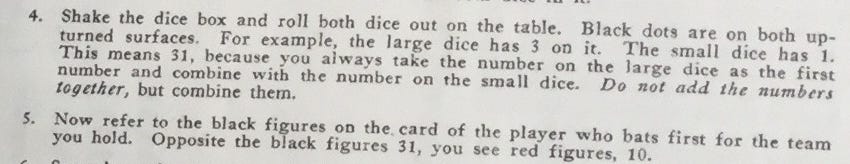

The cards themselves are outlined in a matrix system, corresponding to dice rolls numbering 11 to 66. The easiest way to explain it is to show it to you:

These photos come from a reprint copy of the game that I once owned, but sadly had to sell a few years ago. I’m on the lookout for another copy, in case you have one that you are willing to part with.

Anyway, the numbers in black on the left correspond with dice rolls. According to research done in the APBA Journal, National Pastime originally shipped with two white dice, one bigger than the other:

My apologies for the constant references to APBA here; for reasons that will become obvious as we move along, most people who have studied National Pastime have done it while wearing APBA-colored glasses. The part of the instructions that this article was referring to can be seen here:

In short, those cards are a matrix system to represent actual player offensive accomplishments during the regular season. Most players were based on their 1930 regular season performances; Rogers Hornsby, who played only 42 games in 1930, allegedly received a playing card based on his 1929 season (though I’m not certain this is correct).

Accuracy

Now — is this simple system accurate?

It is from the accounts I’ve read. I haven’t been able to find anybody who has replayed an entire season to provide proof, however.

One reason why most modern gamers won’t play an entire National Pastime season is because the game comes with no pitching system, and really no fielding system. In theory, offensive statistics will come out correct if you play through an entire season. The reality, though, is that you will likely find yourself going nuts when Lefty Grove gets shelled frequently in his starts.

There isn’t much of a fielding system here, either. The cards came with no real fielding designations beyond “Pitcher,” “Catcher,” “Infielder,” and “Outfielder”:

And those who dislike having small rosters will be shocked to discover that National Pastime only included 18 cards per team.

Failure

The biggest piece of surprising trivia about National Pastime, though, is that it was a spectacular commercial failure.

I’m going to get into more detail on that front next time. I’ve discovered a few things that might shock you, no matter how much you thought you knew about this game.