National Pastime's Copy Protection System

I’ve written some pretty geeky articles about National Pastime over the last year and a half. This one, though, is going to take the cake.

There’s a distinct pattern to the way that Clifford Van Beek changed numbers on his batter cards. It’s kind of hard to explain, and it’s a little bit difficult to show — but let me give you an example.

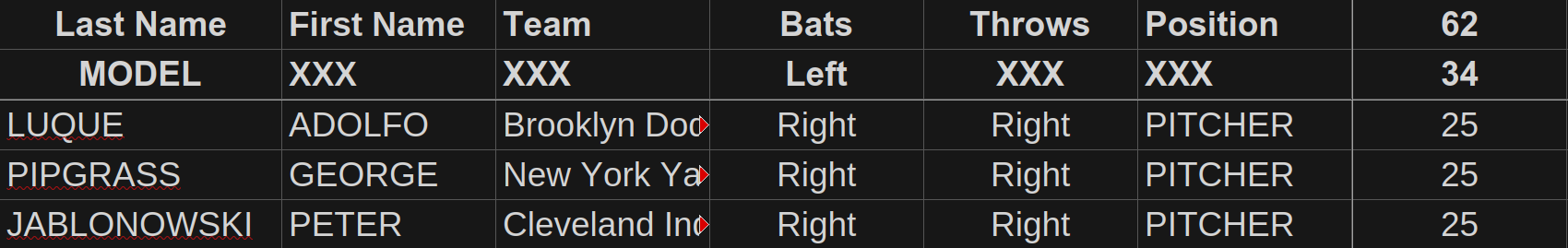

This is the revised model card for right handed batters that we came up with a few days ago:

We’re going to look at dice roll 62. Dice roll 62 results in a 34 on around 58% of the cards.

Now, a lot of cards have a 13 instead of 34 on dice roll 62. We’re not going to worry about that. I frankly have no idea how in the world Cliff decided to assign 13s, and am starting to believe that his method will remain a mystery for a long time.

The interesting thing here are the players who wound up with something other than a 34 or a 13 on dice roll 62.

30 players in all did not receive a 34 or 13 on dice roll 62. Those players received all sorts of play result numbers on that dice roll. Let’s look at an example:

These three right handed batters — all pitchers — received a 25 on dice roll 62.

Now, we would normally expect play result 25 to fall on dice roll 12. That would be in keeping with our model card above.

However, those three right handed batters all received a 34 on dice roll 12:

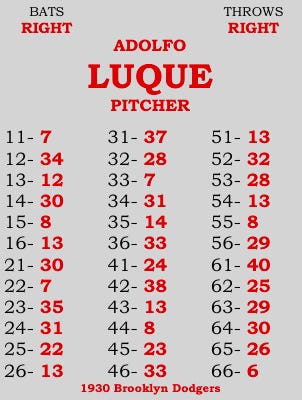

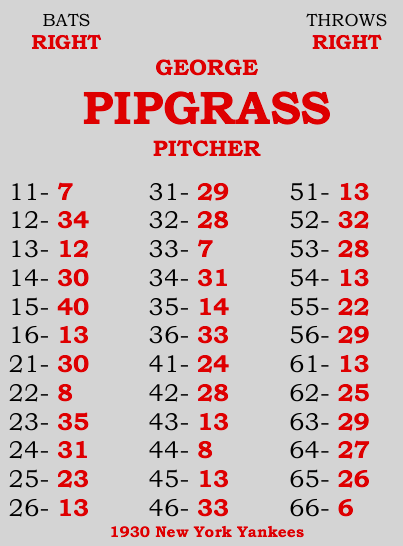

Here are the cards in question:

The interesting thing here is that these cards contain other instances of switching things around. Compare these three cards to the model card, and you’ll see what I mean.

Luque and Pipgrass received PRN 12 on dice roll 13 and not on 63. On dice roll 63, they received a 29, which just so happens to be what Jablonowski received on dice roll 13.

Now, we don’t really have enough players with a 29 on dice roll 13 to conclude that this was part of Clifford Van Beek’s model card. However, I’d argue that the evidence here is pretty strong.

Additionally, Pipgrass and Luque receive a 30 on dice roll 14. We’d normally expect that 30 on dice roll 54, and a 27 on dice roll 14. Instead, both have a 13 on dice roll 54. While both hitters have a 30 on dice roll 21, which we’d expect, Luque winds up with an extra 30 on dice roll 64, and Pipgrass winds up with only a single 30 on his entire card.

See what I mean by complicated?

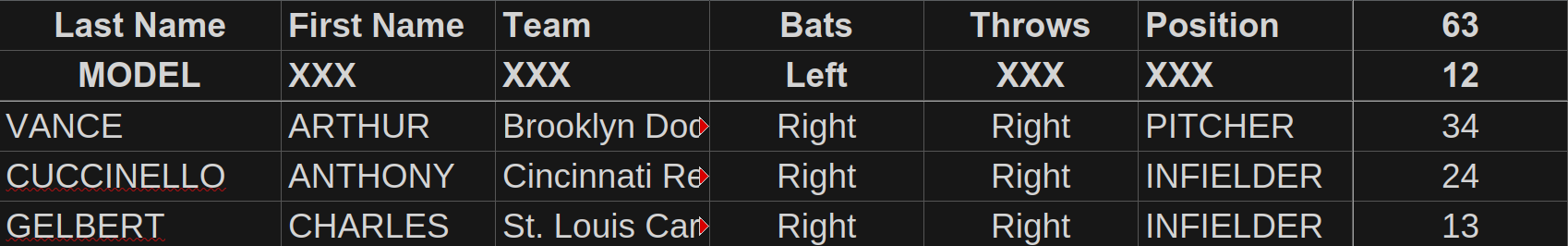

The following three right handed hitters received a 12 on 62, not on 63:

As you can see, this doesn’t just apply to pitchers. And, interestingly, the number they received on 63 is different:

Remember that we normally expect PRN 34 on dice roll 62. In other words, Vance’s card shows the one for one swap. I also think we can assume that Gelbert received a 13 in place of a 34, though, like I said, it’s really not clear how Van Beek decided to assign the 13s.

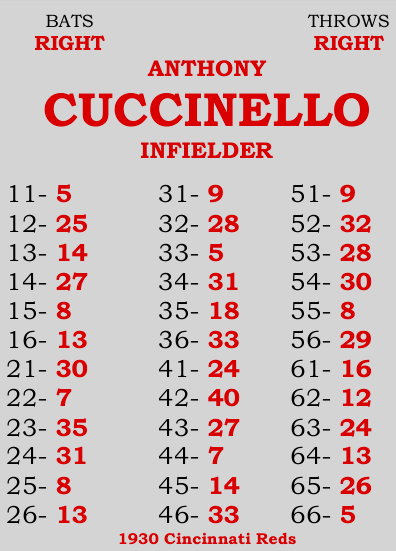

Cuccinello’s 24 is interesting. This is what his card looks like:

For reasons I really don’t understand, Cuccinello has an extra 24 on his card. We expect to see a 24 on 41, but not also on 62 or 63.

My guess is that the 24 on dice roll 63 actually was supposed to be a 34, since Tony doesn’t have a single 34 anywhere on his card. Almost all right handed hitters have two 33s and one 34, but Cuccinello only has the two 33s. Perhaps this is a printing error.

Aside from that, Cucinnello’s out numbers match our model card precisely, with the exception of a few 13s thrown in here and there.

This isn’t just a right handed hitter thing, either. The exact same thing happens with left handed hitters and switch hitters. Recall that we came up with this modified model card for left handed hitters and switch hitters:

In this case, we expect to see PRN 26 on dice roll 62. We see that about 70% of the time.

As usual, the exceptions are where things become interesting. We’ll ignore unusual play result numbers and 13s and will look instead at these two players:

Note that these aren’t the only left handed hitters with something different on 62; they just happen to be the examples I chose.

We normally expect to see PRN 31 on dice rolls 23 and 63. Here’s what these guys have on 23:

And here’s what they have on 63:

There’s the missing PRN 26.

We can keep playing this game, by the way. Sometimes there was no swap: at least four left handed batters received three PRN 31s, for example. Sometimes the swap can be difficult to spot, since it involves three different dice rolls. Sometimes the interpolation of 13s, play result numbers 15 through 21, and play result numbers 36 through 41 complicate things.

But there is a pattern here — and, once you learn to see it, you’ll realize that it’s all over these cards.

Now, this isn’t to say that every card shows this kind of swapping. I thought that at first, but I was wrong. It turns out that 20 out of 111 left handed and switch hitting cards match the “model” card exactly, with no swapping. An additional 16 cards only show one number difference, which means we suspect that there was no swapping. For right handed batters, 27 out of 177 cards show no differences, and an additional 23 show only one number difference. In other words, 86 out of the 288 National Pastime cards seem to follow our theoretical model, or about 30%.

However, the other 70% really pose a problem for reading and analyzing cards.

My theory is that Clifford Van Beek included this as a type of copy protection mechanism for his game. Because the pattern changes at seemingly random intervals, it must have been extremely difficult for players of his game to figure out how the cards worked. Even when we use modern spreadsheets to analyze the cards, the jumping around without even as much of a hint of a pattern makes things really confusing.

There is a chance that these are all printer errors, of course. Maybe one of those 31s on the four hitters who received three of them should have been a 13 instead. But, when you start graphing it out and comparing player cards, you don’t see a lot of examples of obvious printing errors. Instead, it looks like this swapping was done deliberately.

My other theory is that some of these alternate out card placements reflect an earlier version of National Pastime cards. Perhaps the patterns changed over time. However, the play result number flipping does not follow any discernible set pattern, which is what we’d probably see if Van Beek were accidentally reusing older versions of his hitting cards.

I think this swapping is deliberate, and, as odd as this sounds, I think it was done precisely to prevent exactly what I’ve been doing.

As usual, the card designer has had the last laugh.

Don't forget that the concept of "automatic" results hadn't been established yet, since Van Beek was starting from scratch when it came to individual player cards based on stats. We can see that he wanted to keep the hits in a hierarchy, but I think he may have wanted to make sure the other numbers behaved less predictively, so people would have to look at the cards while playing as opposed to knowing just what to expect (as I think most APBA players do on a 12/32/52, 14/34/54 etc, dice roll).

And re Cuccinello's 24 result instead of 34, it may be worth mentioning that you're working from a reprint of the NP set. (The original set didn't have team names on the cards.) So if it's a typo (and I think it is), it could conceivably have happened in the reprinting process.