Overusing Jim Dyck And Joe Ginsberg

It’s been a while, but you might remember the old Baseball Think Factory thread that I mentioned in earlier posts.

If you don’t remember it, you can catch up here:

Were the 2006 Yankees an All Time Great Team?

This post includes affiliate links. If you use these links to purchase something, this blog may earn a commission. Thank you. Beginnings It all started so innocently. Back when I was in high school, I stumbled across a website called Baseball Primer.

Long story short: back around Christmas 2005, a group of baseball geeks got together to argue about whether the 2006 Yankees would have one of the greatest offenses of all time. Actually, the 2006 Yankees did have an incredibly good lineup, one that has been forgotten as the years have gone by.

Eventually this turned into a long argument about which teams are the greatest of all time. At some point in time, somebody decided that it might be fun to turn the argument into a Diamond Mind Baseball season.

We’ll get into the pros and cons for individual teams later. For now, we’re going to focus on the replay itself, what happened, and what we as replayers can learn from it.

The Setup

As reported in the opening post to this thread, the original plan was to get the 28 best teams in baseball history, play 1,000 simulated seasons, and then report the results.

That’s incredibly boring, of course. While a thousand simulated seasons might tickle your analytical bones, it really makes for boring blog reading. As a result, this project quickly turned into a single season project, with the computer manager controlling the rosters for each team.

The guy playing through the games decided to have the computer simply autoplay everything. He ran a website with weekly boxscores and frequently updated stats. The original website is gone, but you can find early archived versions here.

The replayer made a pretty simple organization: two leagues, dividing up the teams by year, 14 teams per league:

The Problem

So what’s wrong with all this? Where’s the problem?

The problem is that Diamond Mind Baseball didn’t stop itself from overusing certain players.

Specifically, two members of the 1954 Indians — Jim Dyck and Joe Ginsberg — were used so frequently in this replay that it helped the Indians win the pennant.

This discussion shines a bit of light on the issue:

Okay, let’s give you some background.

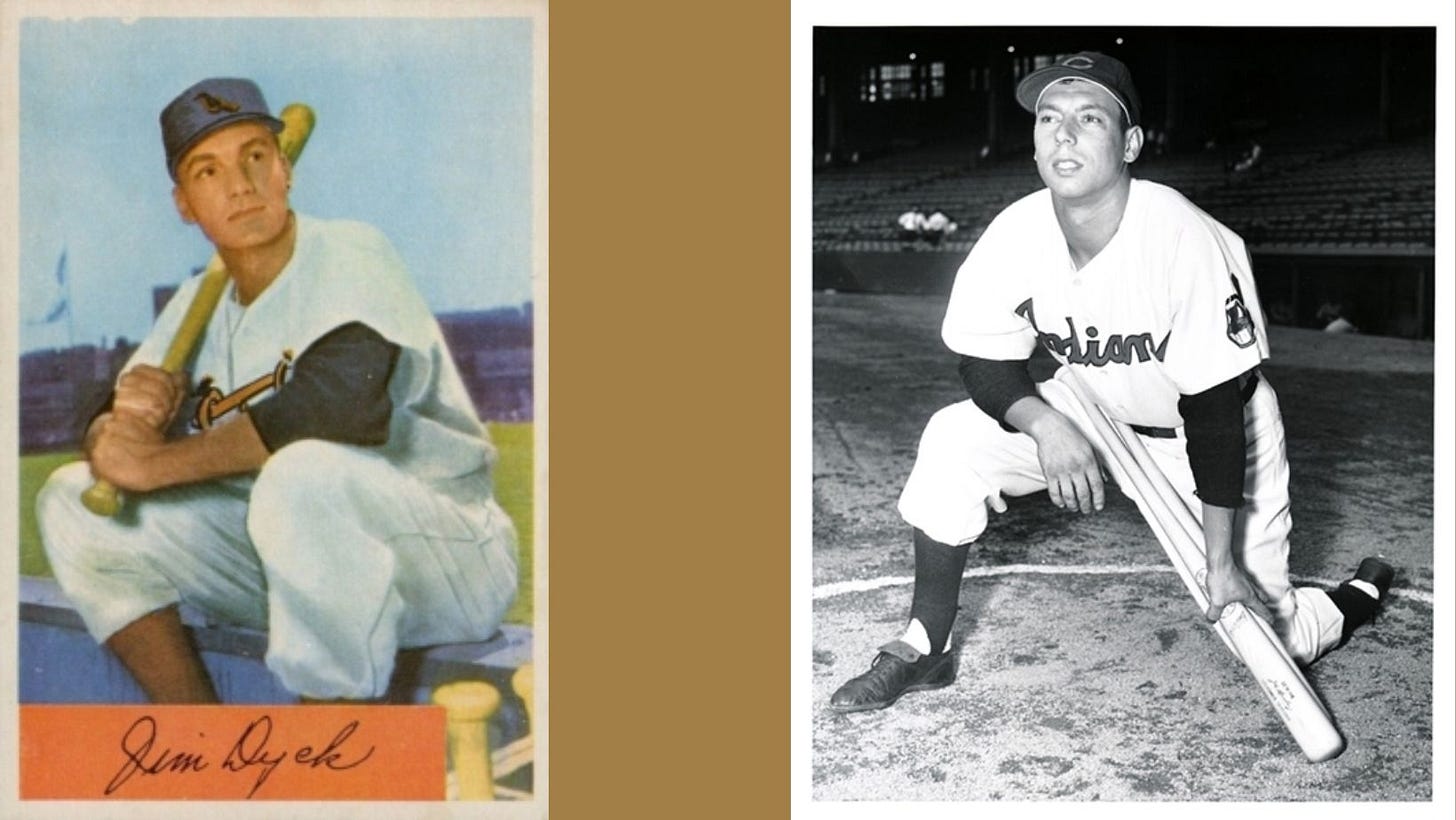

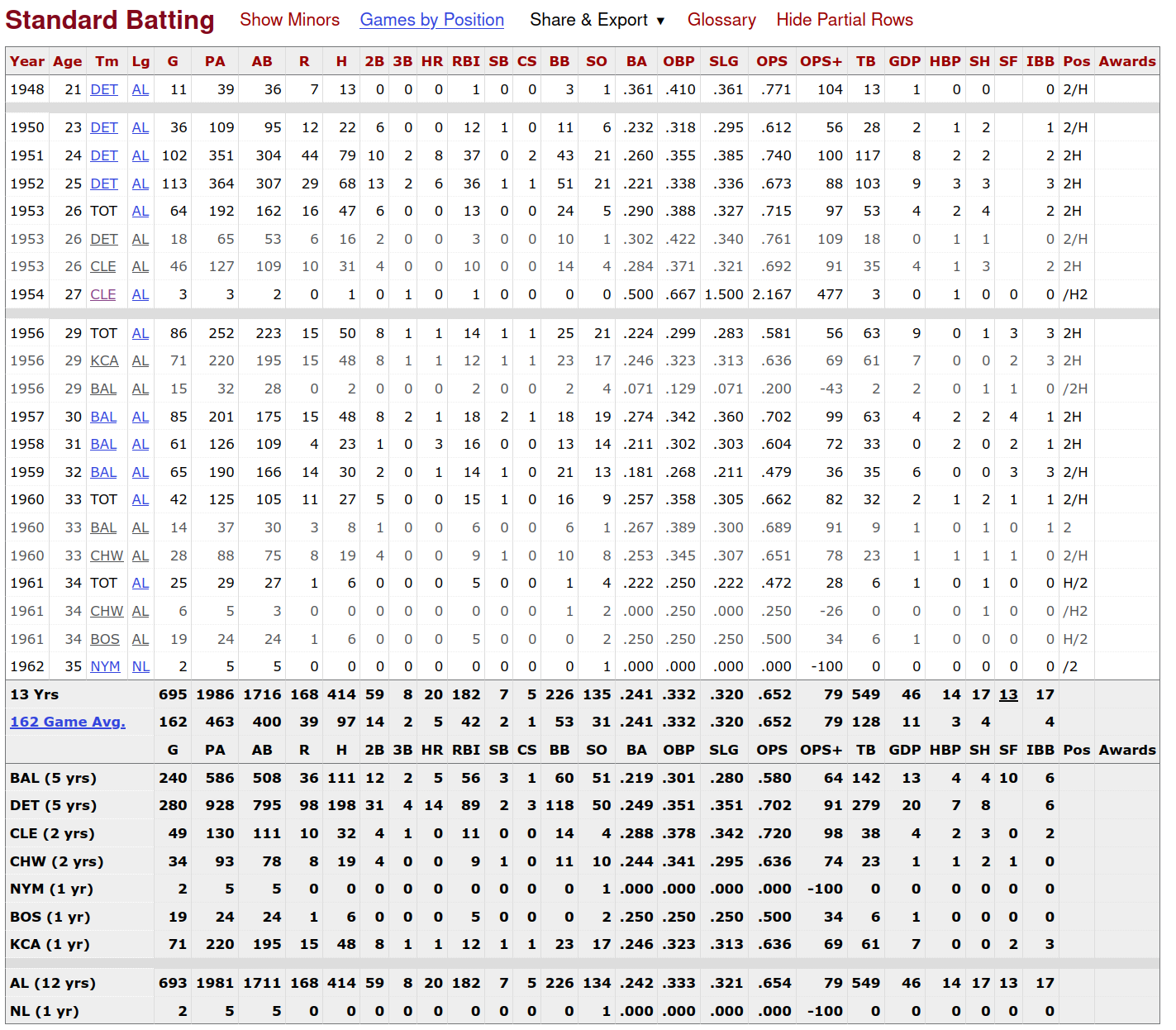

Jim Dyck was a weak hitting utility man. He entered the major leagues in 1951 at the age of 29, hung around for a few years, and moved on:

Dyck spent most of the 1954 season in Richmond, coming up to the big club for two pinch hitting appearances in late September, long after the Indians had clinched the pennant:

It’s pretty obvious that Dick’s 1.000 batting average in 1954 — a single and a walk in two plate appearances — is not indicative of his actual skill level.

Joe Ginsberg was a backup catcher for most of his career:

Joe had 3 pinch hit plate appearances in 1954, gathering a triple and a hit by pitcher in the process. He appeared twice in late April and once in early May before joining one of the greatest minor league teams of all time in Indianapolis:

In other words, that .500 batting average with a 1.500 slugging percentage and a crazy 477 OPS+ is not indicative of Ginsberg’s abilities.

The problem in this replay project is that the 1954 Indians would win games like this:

The boxscore isn’t perfect, but you can get the gist of it. Both Dyck and Ginsberg pinch hit. Dyck walked in his only plate appearance, and Ginsberg wound up going 1 for 2 with a triple. By the way, Ginsberg was hitting .495 at this point in the season, and Dyck was hitting a modest .823!

Yeah, that’s not good.

Lessons Learned

If you’re interested, here are the final standings:

Honestly, this looks like it was a great idea and a fun project. However, it is a tad unrealistic when you’ve got one guy with an OPS of over 2.000, and a teammate of his with an OPS near 1.700. Ginsberg was clearly a triples machine.

So what do we learn from this?

Transcations Matter. You need to make sure that players are set up for realistic usage. Ginsberg should have been on the 1954 Indians for about two weeks at the start of the season. Dyck should have only been there for the final week of the season. If you give the computer (or, heck, another human) the ability to misuse these players, you’re going to have some bizarre results.

Player Roles Matter. To put it another way, you’ve really got to do your research before the project starts. If you just take a bunch of teams and throw them out there without carefully setting things up ahead of time, you’re going to wind up with odd results and a project that just isn’t much fun.

Rules Matter. The rules of this project were never really clearly established. You can’t just rely on things like Diamond Mind’s “limit bench playing time” option and expect to get something that works well. If you want good results, you need to clearly define how you’re going to deal with teams of different sized bullpens and rosters, for example.

Autoplay Is Not The Answer. We all want quick results, I know. This particular project started on February 3, 2006, and ended on August 12, 2006. That’s not a short project — but, seriously, for a project of this scope and magnitude, I wouldn’t be upset if it took several years before it ended. Why not manage the lineups yourself, manage at least one team in every game, and take your time?

I’d love to know what you think about this long-forgotten project.