Properly Using Closers

This question popped up on the Season Ticket Baseball Facebook group a few days back:

This is actually a good question. And the answer, unfortunately, is not just “it depends,” but it’s a messy version of “it depends.”

I could probably write a long essay on this subject. I suppose I could also just reprint a bootleg copy of Bill Felber’s excellent essay “The Changing Game” that is featured in some of the old editions of Total Baseball.

But it’s not fun to go into deep detail with a bunch of numbers and charts that you’re not going to read anyway.

Let’s look at a few players instead of general trends. This should sort of give you an idea of how things changed. We’ll go backwards in time.

The Diva

The modern closer is to baseball what divas were to opera in the 19th century.

The modern closer is finicky and temperamental. His entrance is a grand event, marked by a lot of fanfare and hoopla.

My dad and I took a trip around the country back in 2001. I suppose with was a riff on those old MasterCard commercials. We hit something like 10 games in 8 cities in 2 weeks. And I noticed that every single stadium followed the same pattern for the closer.

If the home team was leading going into the top of the 9th, the music would start playing. Fans would get on their feet to cheer. The closer would make his grand entrance, like the matador entering the stadium. Some stadiums even had a light show, something that I’ve heard has become only more common across the country since.

This is the Mariano Rivera model. The closer essentially only entered the game in the 9th inning, barely pitched more innings than his total number of appearances, and finished nearly every game he appeared in.

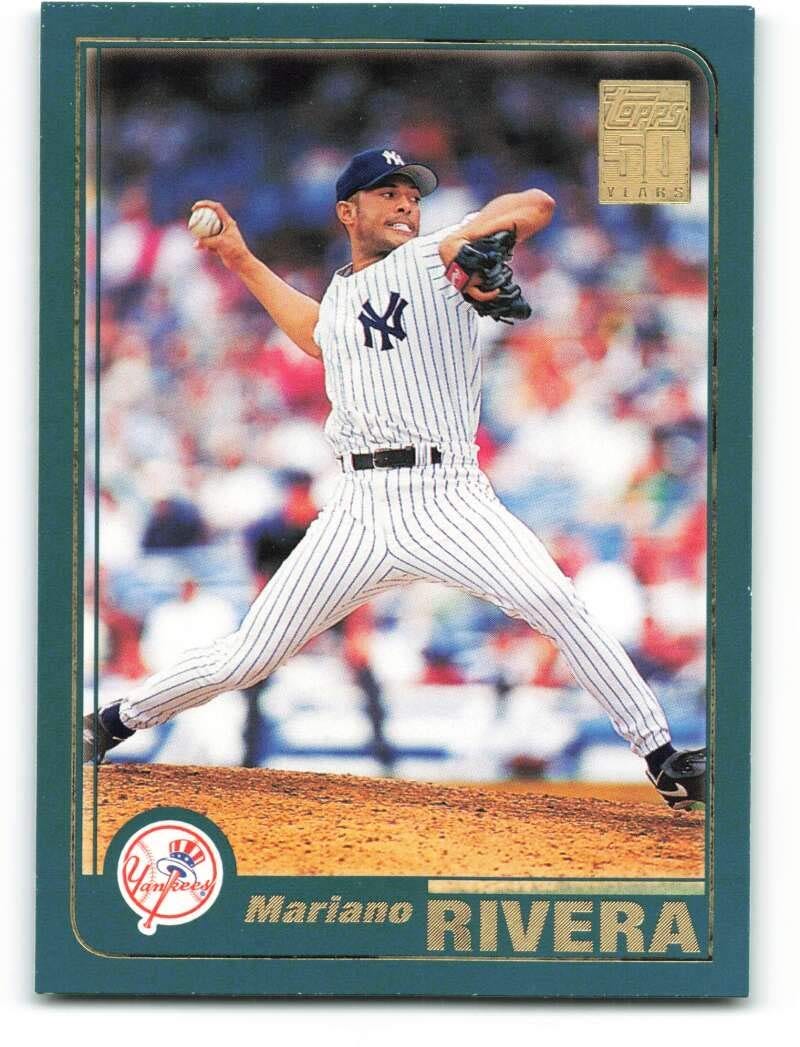

In 2001, Rivera almost always entered the game in the 9th inning:

He’d only come in a little bit early if the game was close and the Yankees were about to blow it.

He also didn’t last long. Out of 71 appearances, Rivera had a grand total of 4 appearances that lasted 2 full innings in 2001:

Now, to make this happen you’ve got to have a pretty well designed bullpen. You need to know who you want to stick in there in which situation. You’ll need somebody who can hold the opposition down long enough before you get to Enter Sandman time. And that’s where the modern bullpen situation tends to come from.

It’s the Diva era of relief specialists.

The Fireman

Go back a few decades and you’ll run into a different type of closer: the fireman.

This was the guy who came in to put out fires and try to nail down wins.

Firemen type closers tended to have more multiple inning appearances. They also tended to need a little more rest between appearances.

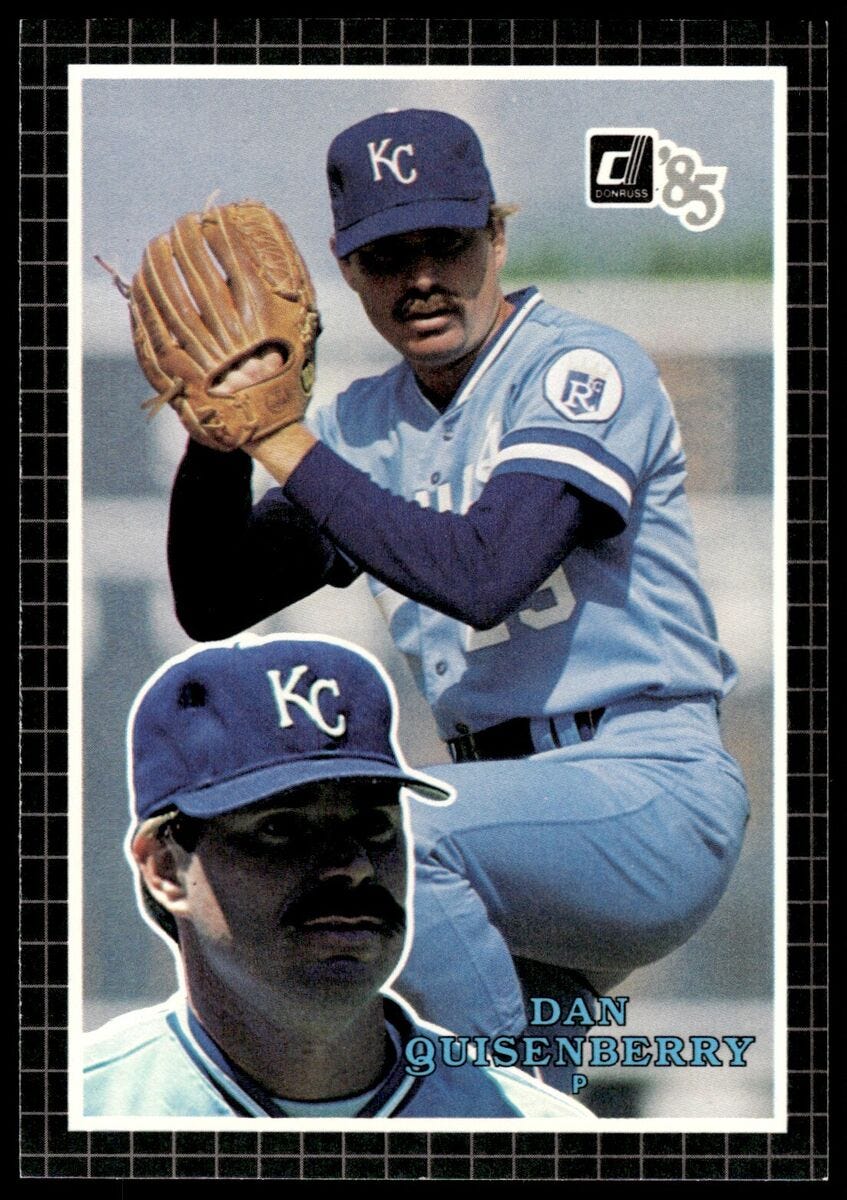

Let’s look at Dan Quisenberry in 1985 as an example.

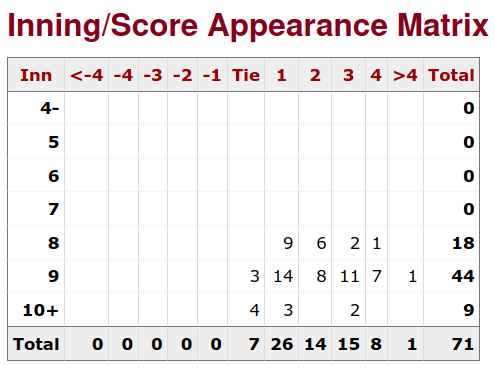

As you can see from this chart, Quisenberry tended to enter the game earlier than Rivera did:

Less than half of Dan’s entrances came during the 9th inning.

Also, notice that he tended to come into ballgames that the Royals were losing. His job wasn’t just to take the team home to victory. He was more a full fledged member of the bullpen.

You can see that when you glance at his workload. He had 29 appearances of 2 full innings or more:

This was the era of using the fireman to put out whatever fire came up — a real blue collar era of the closer. There was no light show and no special music for Quisenberry.

The Premodern Closer

Now, if you keep going backwards, you’ll start running into relief pitchers who basically served as secondary starters.

I think Joe Page is a good example of this.

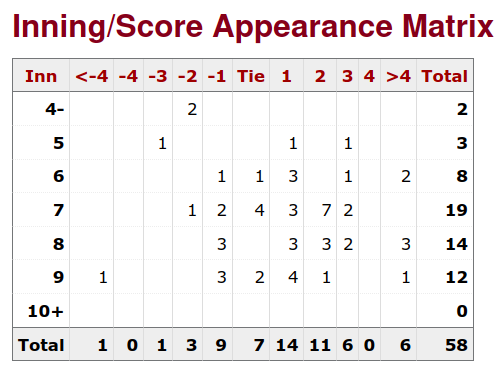

Take a look at when Page entered the game for the Yankees in 1949:

This is the extreme opposite of Mariano Rivera. Page would come in at basically anytime, and in just about any situation. He was a vital pitcher for the Yankees in 1949 — and he put in a lot of hard work.

Of Page’s 58 appearances, 33 (over half) were for 2 full innings or more:

Mariano Rivera was a great pitcher, but he wasn’t going to give you 6 2/3 innings in a vital early October game against the Red Sox.

Relievers Before The Closer

And, finally, you’ve got the real ancient history.

We can see this trend with just about any team before World War II. If we go back to the years before World War I, though, it becomes even more obvious.

Let’s look at the 1912 Detroit Tigers as a whole to get an idea.

First of all, you’ve got a bunch of guys on teams like this that pitched a little bit here and there — usually under 10 appearances, most of which were starts. These guys tended to be young kids who were out of the big leauges as soon as they entered, or washed up players who found themselves back in the minors:

Modern sims such as OOTP have a real hard time dealing with these players. The computer manager tends to be on the lookout for pitchers who can fill modern relief roles. It usually doesn’t really know what to do with a guy who started 2 games, appearaed in 3 more, threw a complete game, and only pitched 14 2/3 innings all season.

This was the era of expecting pitchers to finish what they started, no matter how bad it was. And you can see that when you look at the more regular pitchers:

Calling Tex Covington a “relief pitcher” is ridiculous, since he started 9 of the 14 games he appeared in.

The truth is that the Tigers were much more likely to use a starter in relief than someone like Covington if they were in a pinch.

Jean Dubuc, for example, kind of looks like a reliever if you ignore his starts:

But, of course, there’s not much of a pattern here. And you can see that when you glance at his full game by game pitching record:

So What Do We Do?

So what do we do when we’re trying to figure out how to manage our bullpen?

Well, the first thing is to spend some time before you start your replay to research how the bullpen was used. Did some teams rely on the old school method of using starters in relief (like the 1949 Philadelphia Athletics)? Did some teams have a bullpen ace who almost always closed? Can you find evidence that certain pitchers were supposed to come on in certain innings (a hallmark of today’s game)?

The second thing is to research the fatigue system your game includes. Are there certain limitations you need to be aware of? Are there penalties that will likely limit the number of effective innings pitchers will pitch? And, on top of that, are there historical reasons why you might want to keep a guy in there even after he’s lost his best stuff?

Finally, remember that you don’t need to be a slave to history. While I don’t recommend turning Tex Covington into a Mariano Rivera-style closer, or trying to use Mariano Rivera the way Joe Page was used, you should feel free to create a system that fits best with your playing style.

Don’t fall into the trap of forcing yourself to use the exact same pitchers that were used in relief in real life. Give yourself and your replay some room to breathe, and you’ll find it a lot more rewarding and interesting. After all, this is a game, not a scientific experiment.

The problem here is that every team since the 1990s has tried replicating the Mariano Rivera model but without the same level of success. Rivera was a unique talent who could be used for one inning. In the last few years this way of utilizing the bullpen has broken down and the one inning closer isn’t all that reliable anymore. Emmanuel Clase was phenomenal last year but he and rest of the Cleveland bullpen broke down in the postseason because they were overused. Clase has been so bad this year, Cleveland demoted him from the closer role. Devin Williams, Ryan Helsley, Edwin Diaz have all been terrible as well. Eventually a manager or GM is going to have the fortitude to abandon this model.

Dan,

You are certainly right, especially when it comes to OOTP. Even in the current period, the game will dictate who the closer should be. If one is playing in the preseason mode (2024-2025) the game will list a pitcher (Ian Hamilton0 who is a reliever.