Revenue Sharing in OOTP

It’s never fun to play an impossible game.

If you’re taking control of an underdog team in a small market, you still want to have the chance to win. You don’t want to always play second fiddle just because the Yankees are in New York City and the Dodgers are in Los Angeles.

In theory, revenue sharing is supposed to fix this problem.

I should back up. In the good old days of baseball, team revenues were largely confined to gate receipts. Teams would therefore do whatever they possibly could to draw large crowds. In fact, the tradition of long regular season schedules, along with the now forgotten tradition of local barnstorming during off periods in the regular season, grew up largely to buttress those gate receipts.

This is also why so many old ballparks were so large. While modern ballparks are constructed with an eye towards site views and the “fan experience,” the classic ballparks we long for were constructed for far more utilitarian reasons. To put it simply — the more people you could cram in, the more money you could get from the gate, and, as a result, the more money there would be for your club.

Naturally, certain teams had an advantage. It was a lot easier and quicker for fans in the city to attend New York Yankees games in 1948 than it was for nearby fans to attend Cleveland Indians games. If you spend time reading through classics such as Veeck As In Wreck, you’ll realize that Bill Veeck spent quite a bit of his time going through nearby towns on personal barnstorming tours, hoping to stir up interest in his product to get those gate receipts up as high as possible. Sometimes it worked, but usually it didn’t.

Revenue sharing was largely unnecessary in those days. And, as a matter of fact, the whole concept really didn’t arise until free agency made the prospect of buying up the best players far too tempting for certain owners to resist.

I don’t want to spend too much time talking about that history. That’s a topic that can wait for later. However, the fact of the matter is that revenue sharing really wasn’t a thing in baseball until after the 1994 player’s strike. And, as you’ll see in a second, it’s controversial for a really good reason.

The most basic form of revenue sharing comes via the luxury tax. This is pretty simple to understand. It was a special tax on the teams with the 5 highest payrolls in baseball. The league looked at the teams ranked 5th and 6th in payroll in any given season, and took the average between those two payroll figures. The 5 teams with a payroll above that average number would have to pay 34 cents tax for every dollar spent above that average.

As described here, the luxury tax threshold was a payroll of $51 million in 1997 — and the figure increased from then on.

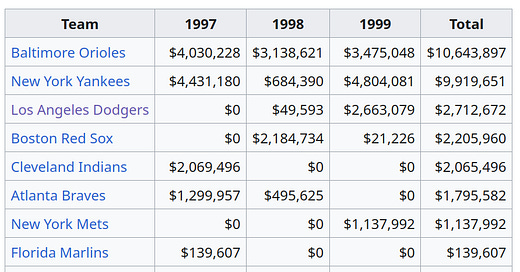

Wikipedia is actually an excellent source on this arrangement. It includes this list of the amounts that each team paid into luxury tax from 1997 through 1999:

Now, did the idea work? Well, it certainly succeeded in convincing the Flordia Marlins to get rid of all star players after the 1997 championship season. The Yankees saw their payroll constantly increase during this time, however, and a number of teams on this list became perennial competitors — challenging the idea that this system created some sort of “competitive balance.”

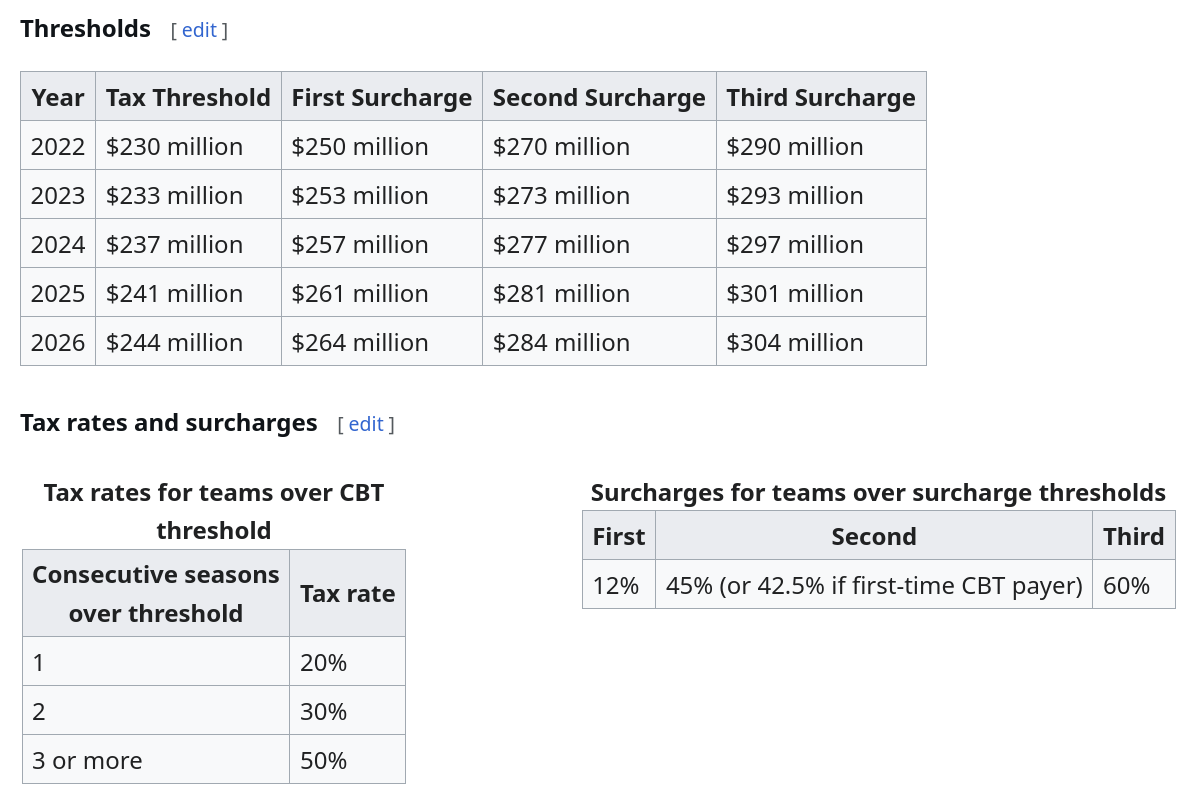

The system changed over time. After a hiatus in 2000 and 2001, the system turned into a simple salary threshold that teams would be taxed on once exceeded. These days the tax rates depend on a number of surcharge thresholds, and the system looks like this:

Of course, if you’ve got unlimited money to play with, the tax means very little. Take a look at the teams paying into the luxury tax over the past 3 seasons:

If this USA Today article is to be believed, the amount of luxury tax the Dodgers paid in 2024 exceeds the entire payrolls of the following teams:

And, of course, you don’t have to be an expert at modern baseball to know the difference in roster quality between the teams on these two lists.

So does the luxury tax work? Nope.

There’s another tool modern MLB uses called revenue sharing.

Revenue sharing is easier to figure out. Each team puts a percentage of “local net revenue” into a pool. “Local net revenue” is stuff like ticket sale revenue, concession revenue, merchandise revenue, parking revenue, and so on. Originally, teams were required to pool 31% of these “local” revenues; this changed a few years ago to 48%.

But this isn’t enough. As this article makes clear, there are a number of major issues:

Teams with an ownership stake in the television station that broadcasts their games can structure deals deliberately to avoid revenue sharing.

Benefits from stadium agreements with local governments aren’t considered at all in revenue sharing.

Certain expenses are subtracted from this “local net revenue,” such as stadium debt and operating expenses. Teams that are creative can come up with ways to effectively “hide” huge chunks of revenue from the system.

And that’s precisely why you see the Los Angeles Dodgers with a monsterous payroll, despite all efforts to stop them.

But this article is about OOTP, right? So what can we do about it in the game?

Well, there are two things we can do. Both options are in League Settings > Financials.

The first is to turn on revenue sharing. By default, it will use 48% as the shared percentage of income, which is precisely what happens in MLB in real life:

You can actually adjust the “shared percentage of income” up to 100% if you like. Naturally, this would take away any economic advantage that one team has above the rest, effectively forcing a hard salary cap. In other words, you wouldn’t be able to spend above a certain payroll defined by the amount of total league revenue divided evenly by the number of teams in your league.

And, since this is baseball, there is also an option for the luxury tax:

The luxury tax works the same way that it works in real life. Teams with a payroll more than a certain percentage above average (or the “soft cap”) are charged a tax. That tax is a percentage of the amount they are above average.

Interestingly enough, you can use a luxury tax even if revenue sharing is up to 100%. This can be an incentive for all teams to reduce payroll beyond a certain amount even if they have enough money for more players.

Now, notice that, for the sake of realism, OOTP has the owner control the budget by default. This mechanism faithfully replicates the famous Nutting Effect, where certain owners in smaller markets deliberately keep spending to a minimum and pocket as much of the free revenue sharing money that they possibly can. The only way to prevent this from happening in OOTP is to force all revenue to be available to each team:

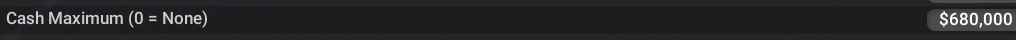

You can also establish a maximum amount of cash that each team controls to discourage this behavior:

The combination of these two factors can effectively create a salary floor, forcing teams to spend at least a certain amount of money on payroll and avoiding the tanking problems we see in modern baseball.

Sadly, though, even with its numerous options and levers, OOTP does not offer the option of creating a salary floor.

However, there is a way to create a “hard” salary cap beyond which no team can spend. This is located on the same screen, but is hidden at the bottom of “Team Expenses & Salary Settings,” below the typical salary ranges for various players:

I’m not an expert on the vast history of OOTP baseball, but I get the feeling that this setting is likely a holdover from earlier versions of the game. At any rate, you can use this setting to establish a salary cap beyond which teams can not go. This is a viable alternative to the “soft” salary cap described above, and might be more palatable than the communist option of sharing all revenue.

Now, if you’re worried about where you should set that salary cap, you can always consult the financial projections listed on the same settings page:

These numbers are based on inputs such as the attendance settings (which we already covered),

the media contract settings (which we already covered)

the luxury tax and revenue sharing settings, as well as merchandise, which we’ll cover in a later post.

My understanding is that the numbers this system churns out them dictate a lot of the free agency settings, which we will cover in a future post.

In short — you can at least come close in OOTP to fixing the many problems with baseball’s current revenue model. In fact, as you experiment with these settings and run sample season replays, you’ll find that OOTP is actually pretty good at setting up competitive leagues where even the worst teams still have a shot at making something happen.