Ron Guidry vs Jim Rice in 1978

I wrote a bit of an introduction to this debate yesterday. Bill James wrote two articles about this in the extremely rare 1979 Baseball Abstract, a book that is impossible to find for a reasonable price even in reprint form. If you don’t believe me, take a look at this eBay auction.

Unfortunately, our insistence on reporting statistics in a Baseball Encyclopedia chart format means that there’s really no easy way for me to show you totals for both players. I’ll do my best with what I’ve got.

Jim Rice had the best season of his career in 1978:

Rice led the American League in triples, home runs, runs batted in, and slugging percentage. He was simply outstanding for the Red Sox, playing in every single game and terrorizing league pitching.

Guidry, on the other hand, really had a season for the ages:

We don’t see pitchers have seasons like this anymore. In fact, we rarely ever see seasons this dominant. The 1.74 ERA was nearly 2 full points below league average. Guidry compiled a 25-3 record, which is the sort of won-loss record that makes you think that it might not have been just good luck after all. While his 248 strikeouts wasn’t quite as many as Nolan Ryan, it was still impressive — and averaging fewer than one walk or hit per 9 innings is amazing when you’re pitching almost 300 innings.

The big question, of course, is how in the world you could compare these two.

Everybody knew that Rice and Guidry were the stars of the league, as The Sporting News reported after the season:

Now, I’m not the only person who recognizes that Guidry did something extremely special in 1978. Leonard Koppett gives us the appropriate historical context:

I guess you could consider this baby steps towards sabermetrics. What is interesting to note, however, is that Guidry and Warren Spahn were the only pitchers on that list on the left with an ERA more than 2 points below league average who didn’t pitch in hitter friendly eras.

Guidry’s dominance led him to sweep through the American League Cy Young award:

Apologies for the unclear text — this comes from the official Sporting News archives. It would be nice to get a copy of some of these issues and do a rescan.

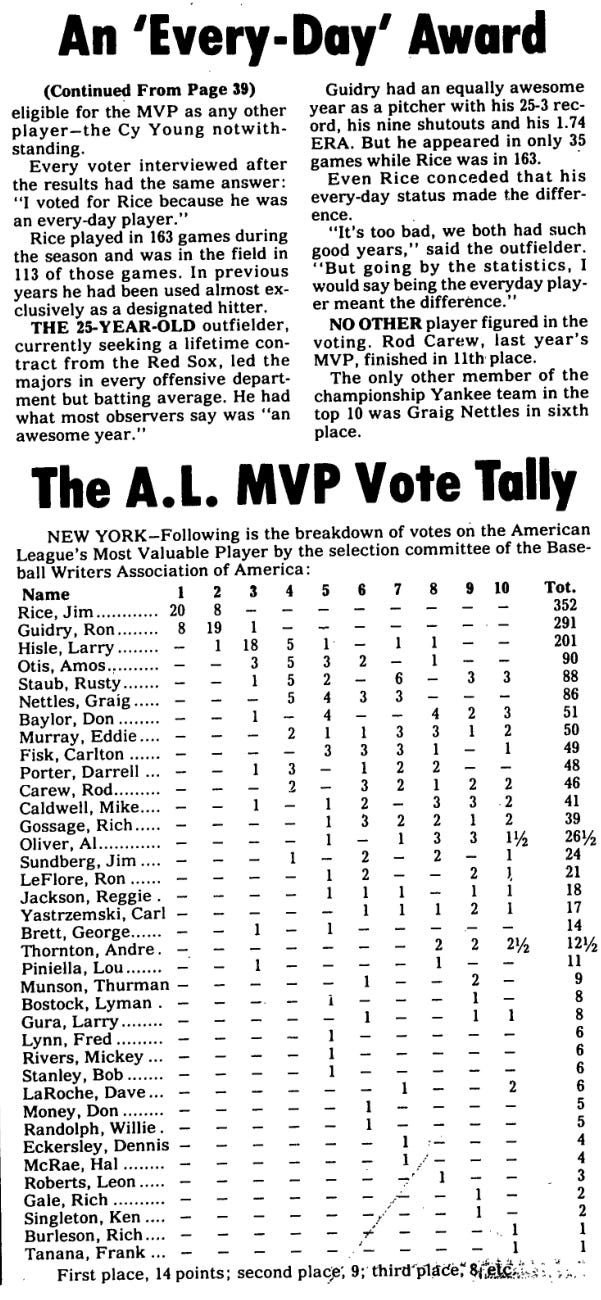

Even with all of that, however, Rice won the award:

Of course, adding to the controversy here was the fact that the Boston Red Sox finished second. In fact, the Red Sox had collapsed down the stretch in 1978, losing the pennant to Guidry’s Yankees. How, then, could anybody conclude that the best player on the second place Red Sox was more valuable than the best player on the first place Yankees?

Anyway, as you can imagine, the New York press was less than enamored with this decision.

As you can see here, the “everyday status” of Jim Rice is what pushed him over the top.

The Boston press, of course, didn’t seem to mind:

Note as well that Rice accumulating 400 total bases is part of what put him over the top. No man had accumulated so many total bases since Joe DiMaggio back in 1937. This, by the way, might explain James’ fascination with total bases that we saw yesterday.

So what do baseball fans today think about all this? Well, most baseball fans don’t think about any of this stuff, which is a shame (and the reason why I’m writing all of this). Those who are familiar with the history, though, will usually say something like this:

Apologies to my fellow SABR member Dr. Wernick, but I disagree that Guidry won the pennant and the championship for the Yankees alone. Guidry pitched only twice in the postseason that year. He was taken out of game 4 of the ALCS with a 2-1 lead after giving up a leadoff double to Amos Otis in the top of the 9th inning — and got the victory when Goose Gossage shut down the Royals. Guidry then threw a complete game victory in game 3 of the World Series — and that was it. I’d argue that some of the other Yankees had something to do with the victory — and I suppose this is another variation on the “everyday player” theme.

But what’s more interesting here is that big discrepancy in Baseball Reference WAR — 9.6 for Guidry to 7.6 for Rice.

I’m not an expert in WAR, and I’ve voiced my criticism of how WAR (and, specifically, Sean Smith) treats fielding several times on this blog and on my YouTube channel. However, I do know enough about the metric to realize that it’s not easy or advisable to compare position players with pitchers directly. In fact, Baseball Reference doesn’t really allow you to make that kind of comparison — the value calculations for both types of players exist in separate tables.

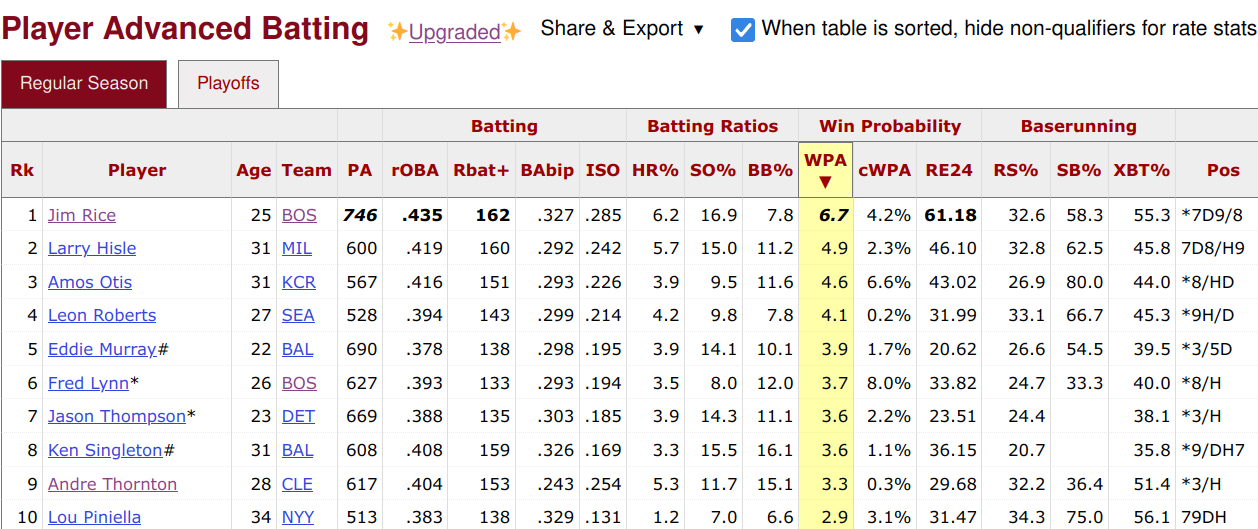

There’s no question that Jim Rice was the most valuable position player in the 1978 American League:

There’s also no question that Guidry was the most valuable pitcher in the 1978 American League:

Now, there are a few quick things I want to note here before ending this.

Position disadvantage. Rice receives a deduction due to his position. I’m not sure exactly what the “-9” here signifies, or what his WAR would be without this deduction — this is largely because of how complicated the formula is. Rice played mostly in left field in 1978, and also spent about 50 games as the Red Sox Designated Hitter. I certainly agree that left field is not as demanding a position as, say, shortstop or third base — but there is a question here about whether the position disadvantage isn’t hurting Rice unfairly. And, as I’ve said before, somebody has to play left field. Note, by the way, that Rice was a good left fielder in 1978: we’re not talking about Dante Bichette here. However, what would otherwise likely have been a positive defensive WAR rating became negative, largely because of that position adjustment.

Double plays. Rice was notorious for grounding into double plays: in fact, he’s tied for 8th on the all time leaderboard for that ignominious stat. Rice ground into 15 double plays in 1978, which was actually one of his better years. WAR gives him a slight ding for those ground balls — correctly, in my opinion.

Role advantage. You can’t see it on this chart, but Guidry received a very slight advantage for his role as a starting pitcher in 1978. Baseball Reference makes this adjustment because relief pitchers generally allow fewer runs than starting pitchers. As is the case with the position adjustment, this really should be a pretty contentious adjustment, especially when you consider that most of what we think of as “pitching” is probably actually fielding. It warrants at least a discussion, in my mind.

There’s another way we can look at all of this, of course. We can compare win probability added for both players.

Win probability added is one of those cool stats that you can only use when you’ve got a full play by play record. We can jump into every single play in a season and determine whether a specific player’s actions improved or hampered his team’s chance of winning — and we can then add up those stats for the entire season. This MLB article is a good explanation of the concept.

As you can see, Rice had the best WPA of his entire career in 1978. And, as you’d guess, Rice led the American League in WPA in 1978:

Guidry, meanwhile, also put up the best WPA of his career in 1978:

Now, you’d think that Ron would have easily led the American League in WPA, right? He won all those games and pitched so well down the stretch, right? Well, not quite:

However, WPA involves looking at events given their importance to each individual game. While it is the job of a ballplayer to win games, if we’re talking about the ultimate goal, we need to focus on championships.

Guidry performs better in the championship version of WPA — but he still doesn’t lead all 1978 American League Pitchers:

Meanwhile, Rice falls to fifth on the list when we figure in what was important to a potential championship:

Now, if you know about the 1978 season, you know why there’s this discrepancy. The highest leverage game of the season was obviously the one game playoff on October 2nd at Fenway Park.

Ron Guidry started the game for the Yankees, going 6 1/3 innings and leaving with a 4-2 lead. Goose Gossage, meanwhile, pitched the final 2 2/3 innings to get the save. As you can imagine, cWPA favors Gossage because the outs he got were higher leverage.

Rice went 1 for 5 that game, driving in Rick Burleson with a 6th inning single. That was, of course the half inning before Bucky Dent hit the famous home run that pushed him above Rice in the cWPA race.

We usually don’t rely on stats like WPA and cWPA for these discussions for this very reason. cWPA is particularly notorious for punishing otherwise good players for having an off game in the most important game for the pennant.

But, then again, we also need to ask ourselves what we mean by “most valuable player.” Wouldn’t the “most valuable player” be the guy who steps up his game when it’s all on the line?

Last but not least, we should look at how Guidry and Rice matched up in 1978. And the answer here might surprise you:

Guidry faced Rice 14 times in 1978. Jim got 2 hits, for a .154 batting average. Guidry also struck him out twice. Note that both of those hits were singles, giving Rice a woeful .154 slugging percentage.

Of course, the sample size there is pretty small. Over their careers, Rice had the upper edge, going 27 for 75 in 83 plate appearances, with a line of .360 / .422 / .653 and an incredible 1.075 OPS.

However, if we’re looking only at 1978, Guidry clearly should have been the MVP. In fact, if you exclude the base hit in that one game playoff, Rice had only 1 hit and 1 walk against Guidry that season.

All in all, I think Guidry should have won the award. But what do you think?

It always bothers me that pitchers are downgraded when compared to "everyday" players.

Yes, full time position players can impact every game, but only to the extent of their plate appearances, base running, and fielding chances.

Pitchers impact fewer games, but impact every batter they face while in those games.

Rice had 746 PA and 261 fielding chances in 1978, a total of 1007 events where he impacted the game. (Base running is harder to quantify.)

Guidry had 1057 batters faced and 60 fielding chances, totalling 1117 events where he impacted the game.

If we assume base running has some effect, and it does, it's fair to say Rice and Guidry impacted the season approximately equally.

So throw out the "everyday player" argument, at least pre-2000.

It might hold a llittle more water today, when starting pitchers face far fewer batters than they did in the 20th century.