The Art of Stalling

Special thanks to a friend of mine on Facebook for pointing this one out!

Remember when I wrote about outs a few weeks back? You probably don’t: the article didn’t exactly command a huge audience. If you don’t you can read it again, or you can watch this video I whipped together on the subject:

One of the things that gets missed when we talk about outs is the art of using outs as a weapon. Back in the olden days (and the not-so-olden days), outs could be used to stall the game in hopes of rain or darkness wiping the whole thing out. The combination of one team refusing to put the other team out in hopes of stalling the game, combined with the other team purposely making ridiculous outs in the hopes of making the game official, often made a farce out of the sport.

It also made for great stories.

July 14, 1915

Let’s go back to July 14, 1915. The White Sox hosted the Philadelphia Athletics on an overcast day in Comiskey Park.

Yes, the Athletics were defending American League champions — but you have to remember that this was 1915. Connie Mack had already sold the stars, and this version of the Athletics was actually one of the worst teams in the history of baseball.

The White Sox, meanwhile, looked pretty good:

Remember, of course, that this was also the second (and final) year of the Federal League, which meant that the Chicago sports sections were a little crowded.

Now, the other important part of this story is the weather report:

As you can see, the weather clearly called for an afternoon or evening rainstorm. Not exactly great prospects for a baseball game set to start at 3 PM!

The Game

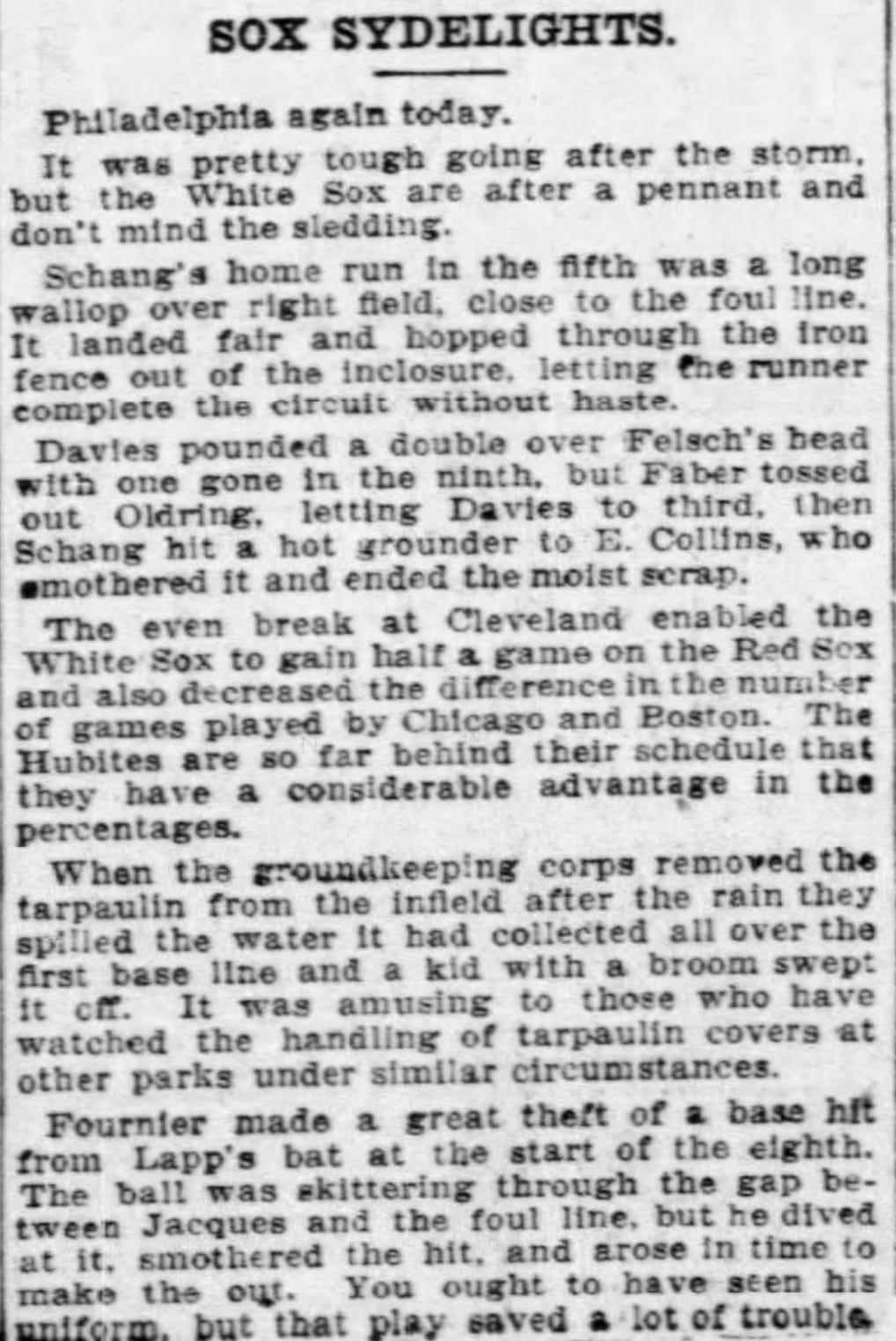

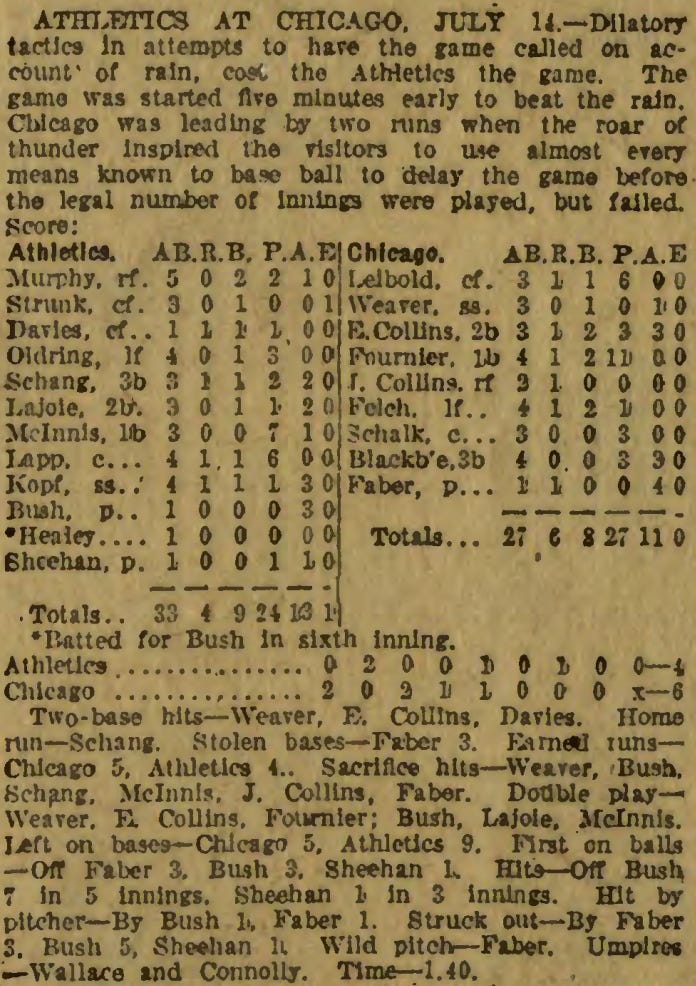

This game was nothing short of bizarre:

What’s missing in this article is the fact that the White Sox were up 4-2 in the bottom of the 4th. After a quick rain delay and amidst swirling winds and claps of thunder, it must have been obvious that they weren’t going to finish the game.

And that’s why the Athletics started trying to walk every White Sox hitter in sight, hoping to prevent the game from becoming official.

In other words, this was one of those rare instances in which the offensive team was trying to be put out, and the defense was trying to keep them at bat.

Now, the real irony here is that the rain never came. The game wasn’t washed out at all. Instead, the Athletics found themselves behind, and wound up losing, 6-4.

It’s interesting to note that the game only lasted an hour and 40 minutes, even with all that ridiculousness in the 4th inning.

Sadly, I wasn’t able to find a Philadelphia paper for this game. However, I did find this blip from New Jersey:

Now, that’s not entirely true. The White Sox won 6-4. Yes, Faber’s run meant the 5th run and the go-ahead run, but it’s not like it was a close game at that time anyway. And they forgot to mention that he stole all 3 bases due to defensive indifference — something that Baseball Reference also doesn’t mention:

I suppose you can give Faber credit for stealing those bases, though the description makes it sound like nobody even tried to put him out.

Meanwhile, it’s pretty obvious that Blackburne and Leibold swung at anything they could see. I’m not sure how Buck Weaver managed to get himself tagged out, though.

I was also unable to find anything in The Sporting News about this bizarre game. Note that The Sporting News did not include game summaries with the boxscores in 1915. Sporting Life did have a brief mention of it:

And, well, that’s all I’ve been able to find so far.

So What?

So what?

Well, this goes to show you that outs are the true currency of baseball.

Look — you can’t throw away a run. You can’t sacrifice a run for the good of the team. You can’t take one of your runs and give it up to the other team in exchange for some good thing that wouldn’t have happened otherwise.

You can sacrifice outs, though. You can give up outs to get something of value for your team in return — an extra base, a run, or even the chance of getting the game to become official.

One of the fascinating things about baseball in the wilder days is the extent to which unorthodox strategies were employed. In this case, you could actually argue that Faber did his team a disservice by not thinking of a way to get himself purposely thrown out. He wasn’t all that fast, of course — in fact, he only had 7 stolen bases in his 20 year career, 3 of which came in this one, when the other team wasn’t exactly trying.