The Discovery Of National Pastime

The tabletop gaming world was a lot different in the early 1970s.

These were the glory days of APBA. Back before Hal Richman’s advanced version of Strat-O-Matic came out in 1972, APBA clearly enjoyed the lion’s share of the tabletop sim market.

In retrospect, it’s easy to see the kind of market share APBA enjoyed. After reading through hundreds of old issues, it’s clear that the first golden age of the APBA Journal began sometime in late 1973, when the expanded publication changed from bimonthly (i.e. once every two months) to monthly (once per month).

And that’s when the discovery took place.

The Discovery

J. Richard Seitz, the creator of APBA, was something of a rock star in the sports sim world in the late 1960s. His famous baseball game was completely different from anything that had been on the market before. Like Ethan Allen’s old All Star Baseball game, which dates back to 1941, APBA featured ratings for individual players. However, APBA was more complex, using a dice roll system that featured better randomization than the spinner and disks, as well as a complex on base system that made deciphering the value of play results difficult.

The Seitz stardom was so strong that he received an extended standing ovation at the first APBA Convention in 1973 before saying a single word.

And that’s when National Pastime was rediscovered.

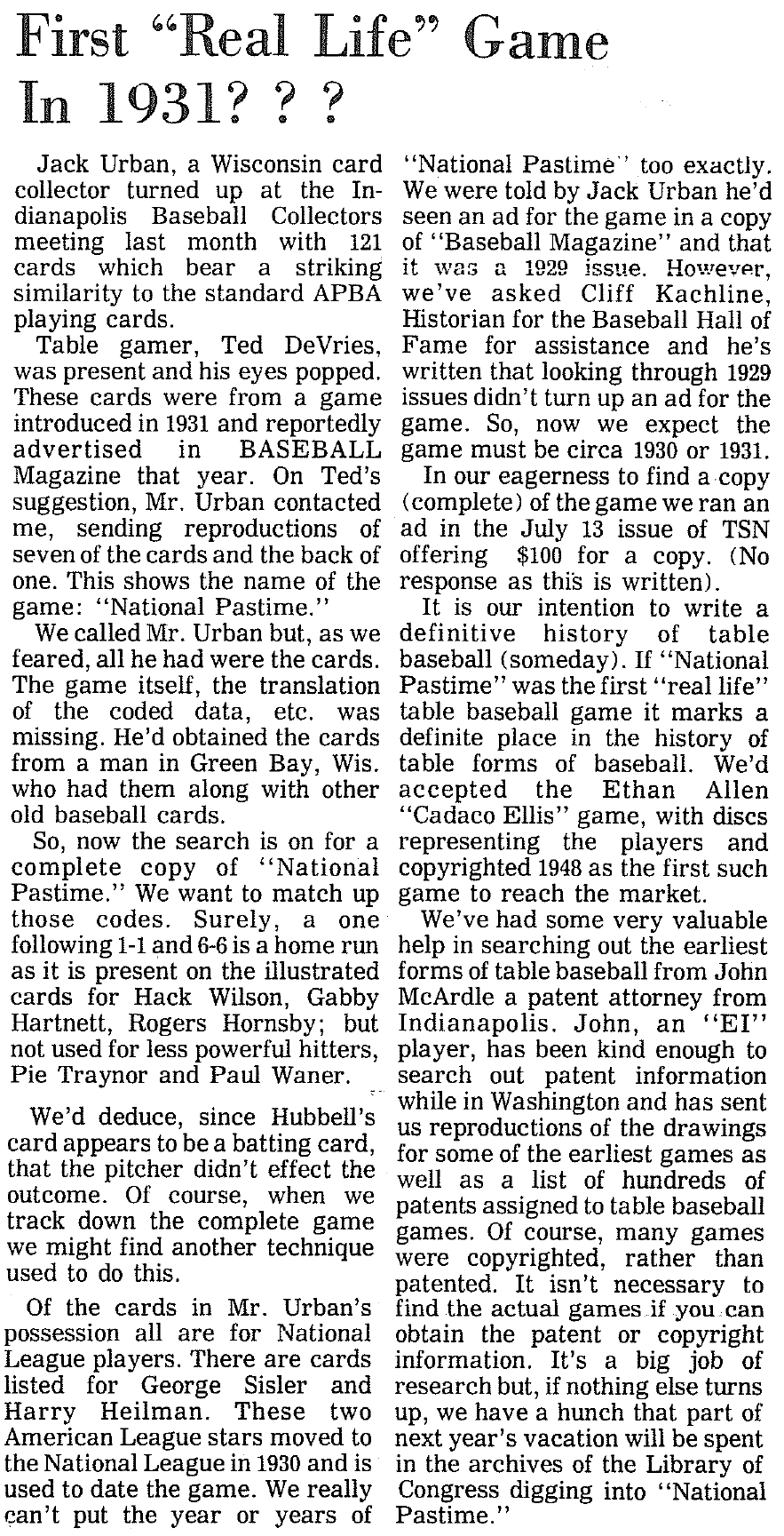

I don’t know the full story behind the discovery of the old National Pastime cards. Thanks to the archive of the old Extra Innings newsletter at Ron Bernier’s site, we know when the discovery was first made public. It was in the July 1974 issue, volume 4 number 2, that this was printed:

Looking 50 years to the distant past is not easy, especially if you weren’t around to experience it firsthand. I’m not sure how widely read the Extra Innings Newsletter was, though I’m convinced its circulation wasn’t extremely high. However, for those in baseball sim circles, this was certainly something revolutionary. This article accompanied the 7 cards:

I’d like to point out a few things here:

Jack Urban’s collection was less than half the original National Pastime run. we know now that there were 288 cards — exactly 18 for each of the 16 teams.

We know that the game was actually originally advertised in December 1930.

This article is the only source I’ve seen that claims there was an advertisement in Baseball Magazine. If you have any copies of Baseball Magazine from December 1930 or early 1931, please let me know.

We also know now that the National Pastime boards were very similar to the original APBA boards.

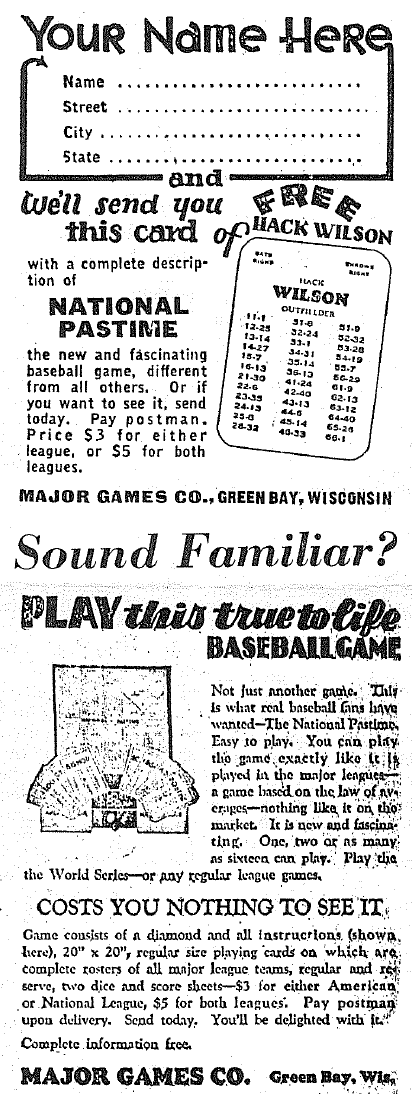

The October 1974 Extra Innings Newsletter featured this reprinted advertisement:

There was also this very brief article:

I’m not sure what happened to their search for the origins of the game. Please let me know if you have any futher information.

The APBA Journal “Scoop”

That leads us to this famous issue of the APBA Journal:

You might not see it in the article itself, but Pete Simonelli and APBA Journal editor Ben Weiser were actually doing a high wire tightrope act with this one.

You see, despite being independent from the APBA Game Company, the APBA Journal was naturally dependent on APBA for its subscriber base. Starting sometime in the late 1960s, new editions of APBA games included advertisements for the APBA Journal.

Without a working business relationship with APBA, the APBA Journal simply couldn’t survive. Sadly, this was not a publication that you could buy on a newsstand or find in the periodicals section of your local library, as I was disappointed to learn around age 11.

That explains some of the strange features of this article:

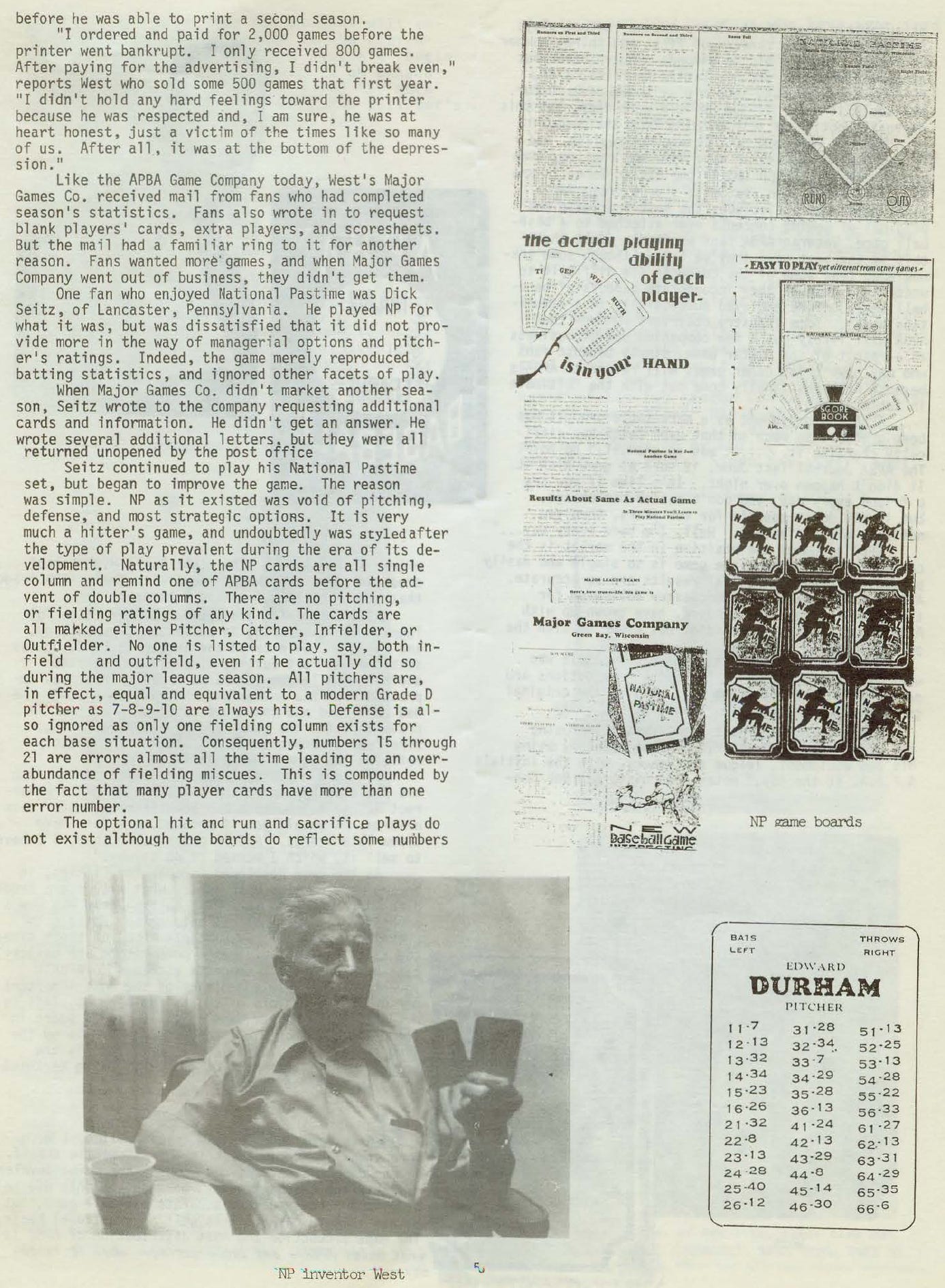

The article is not a “definitive history of tabletop gaming” — not even close. Instead, it’s a feature on Clifford Van Beek and the true origins of APBA.

Clifford Van Beek is referred to by a pseudonym for reasons that aren’t entirely clear.

There are very strong insinuations here that Seitz’ game was actually a copy of National Pastime, though the pictures of the playing boards are so small and unclear that any comparison is impossible. This isn’t due to a faulty scan: the original paper version has the same problem.

There are constant references to APBA being the greatest baseball board game of all time, and insinuations that the APBA Master Game can never be surpassed. I’m going to check the “doubt” button on that one.

You can check these out for yourself in the screenshots above.

Of course, the most fascinating part about this story is that this issue didn’t spell the death of the APBA Journal.

As I understand it, APBA itself was just as dependent on the APBA Journal as the APBA Journal was dependent on the game company. The mid-1970s saw the first full APBA printings of historic past seasons, as Seitz struggled to compete with Richman’s Advanced Strat-O-Matic game. An independent publication devoted to APBA helped Seitz keep excitement alive among his existing customer base for his product. After all, those full color Sporting News ads wouldn’t work if they were pushing the 1949 season, or the 1908 season, or anything like that.

As a result, the truth about National Pastime came out, though in a form that wasn’t entirely accurate. We know now that Van Beek’s game was an utter failure — an example of an over-exuberant businessman ordering more product than he could possibly sell, let alone afford. We know that APBA was largely based on National Pastime, though I’d argue that Seitz’ game featured a number of important innovations that clearly distinguish the two products.

Long Term Impact

And then there’s the long term.

I think I’ve mentioned this part before. My father had a copy of this late 1976 APBA Journal. I read it dozens of times while I grew up. There was something about it that attracted me — something mysterious and hidden, something that felt like a challenge.

I still want to learn more about the true origins of tabletop baseball gaming. We know about a number of games, and we know that dice baseball likely started in the early 1880s in a form that still spreads today.

But the real impact of this has been negative. To this day, you’ll see old APBA fans grumble about how Seitz was a crook, muttering on message boards about how he should have given at least some credit to Van Beek.

The part that I find absolutely fascinating is that this wasn’t the only major challenge that APBA faced in the mid-1970s. There were two other major challenges that did deep damage to the game’s reputation — challenges that we’ll cover in the coming weeks. And the craziest part is that Seitz almost certainly inflicted most of the damage on himself.

I’m keeping the comment section of this post open for all. I’m certain that I’ve missed things, and I’d love to hear from those of you who remember this as it happened. It can be difficult to look back to events that took place long before I was born and try to reconstruct how people may have felt and thought.

The front page of that APBA Journal issue is a reprint of "The Sports Collector", a Sporting News column from July 24, 1976. The Simonelli/Weiser article starts on Page Three. TSN's mainstream mention of the National Pastime game came complete with Seitz being interviewed on the subject: "There's never been any secret that APBA grew out of a game we played as kids. But the only red similarity between the two games is principle. There was no pitching per se in the game we played as kids and the refinements we've done to APBA make it a far more advanced and intricate game than the original." (Undoubtedly easier for Seitz to claim when few had seen the NP boards, but true except for that one not-so-minor detail.)

Anyway, If Weiser as AJ editor had been holding up the story until then, it clearly wasn't a secret after that, though as you note it still had to be treated carefully.

As it turned out, Van Beek had come to the APBA convention that summer and met APBA VP Fritz Light, who was seeing the cards for the first time. Van Beek didn't meet Seitz and wasn't introduced to the crowd; the impression I was given, long after the fact, was that it was fine with him. The pseudonym in the article would seem to suggest that either he or the authors thought he'd be in danger from readers who'd come after him in defense of Seitz; the Simonelli/Weiser story was almost certainly written before Madden's column appeared, when Weiser had reason to believe the disclosure would be more of a threat.

I don't think any of APBA's early amployees had seen NP, but as I understand it at least two of the kids who played in Seitz's league in the 1930s, Wendell Mook and 'Gabby' Doran, were still alive and in the area well into the 1990s. (Seitz made NP cards for MLB players who came up between 1931 and 1936 to keep their league updated, and also made batting cards for himself and all the players in the league, since in the Depression era many MLB teams had player-managers. Reportedly he used dice rolls to generate the number of power numbers and singles, much as roleplaying fantasy gamers would do fifty years later. Anyway, as a result the names of Seitz's league opponents still live on.)

FWIW, the cards that Seitz made show definitively that as a teenager, Seitz knew a lot less about how Van Beek constructed cards than you do now: not necessarily from an accuracy standpoint, but in terms of templates and left/right distinctions.

I’m afraid I have nothing more to add to the national pastime info but I did want to thank you for a very interesting article. I played apba baseball briefly in the 70s, when they came out with the 1930 season. I did not know any details about this. I have always played strat-o-matic baseball. Also enjoy your YouTube content.