The Hall Of Fame Before The Hall Of Fame

The forgotten early days of the Politics of Glory

The Hall Of Fame Before The Hall Of Fame

Baseball’s Hall of Fame has been a topic of discussion for my entire lifetime.

In fact, it’s also been a relevant topic of discussion for your entire lifetime. We’re at the point now where nobody reading this remembers what discussions around the “Hall of Fame” were like before its opening in 1936.

Even Bill James, who penned The Politics of Glory (later retitled Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame?), largely ignores the history of the “Hall of Fame” concept that existed before the Hall itself was created.

Now, the first thing you’ve got to understand is that newspapers had used the term “Hall of Fame” as a rhetorical term for decades before baseball created its famous historical museum. If you start searching through 19th century newspapers for “Hall of Fame” alone, you’ll find a number of references to a rhetorical “hall,” such as this:

The concept behind a physical “Hall of Fame” seems to come from the Ruhmeshalle, a collection of the busts of important people from Bavaria built by Ludwig I in 1853.

This hall received widespread attention in American newspapers, particularly in the late 19th century:

In fact, it got to the point eventually where similar Halls were erected in certain American cities. Take this one from New York for example:

It seems that it was originally established around the turn of the 20th century:

One newspaper claims that the 1911 Spalding Base Ball Guide had a “hall of fame” section:

I’ve been through the entire 1911 Spalding Guide twice now, and can assure you that there is no “hall of fame” section, nor are there even the charts this article refers to. There are portraits of the major players for each team, but there’s not really even a discussion of who would belong in a “hall of fame.”

Of course, there were a few newspapers here and there that used the “hall of fame” concept to create weekly features, such as this:

In general, however, the “hall of fame” concept was mostly a rhetorical device used to refer to players who had accomplished something unusually notable:

The call went out from time to time to establish a permanent “hall of fame,” rather than constantly relying on a rhetorical one in the newspapers. This article, for example, was widely reprinted in 1915:

And that’s also when the notoriously unclear concept of the “hall of fame” really started to show up.

You see — nobody really had thought about how exclusive or selective the “hall of fame” really should be.

I started thinking about this a few weeks back when I came across this Reddit thread about the old “Keltner List,” an article that Bill James had printed in the 1985 Baseball Abstract. James rightly believed that the legend around players like Ken Keltner was probably not enough for them to be included in the Hall of Fame.

The thing is, though, that the legendary fielding exploits of individual players who were otherwise unremarkable goes back to far before the Hall of Fame was officially established.

I mean — would you consider Terry Turner of the 1914 Cleveland Indians a “hall of famer?” Someone apparently thought so back in 1915:

Or what about Jesse Barnes?

Sometimes having a good week or two was apparently enough for a “hall of fame” mention:

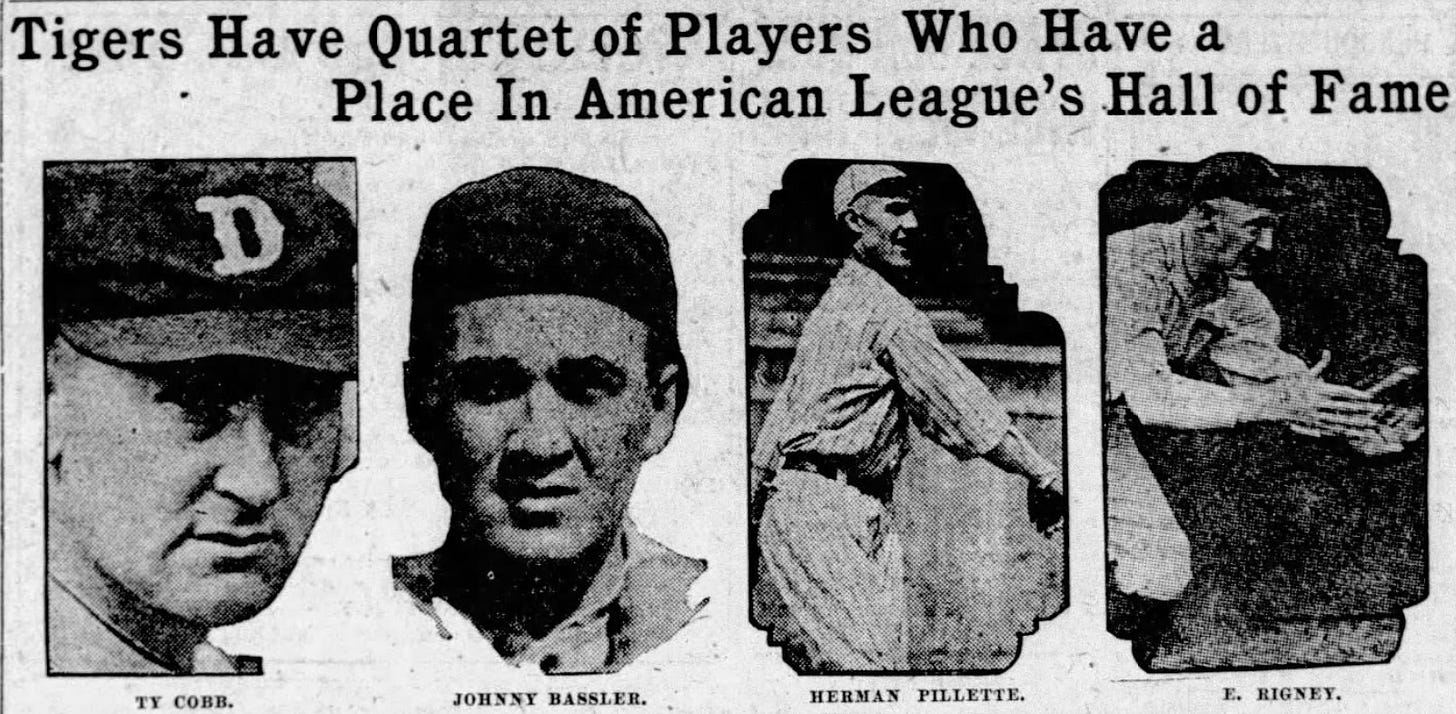

Now, the other thing we’ve forgotten about is that the American League did establish a “Hall of Fame” plaque back in the early 1920s. This was a plauqe that was apparently set up somewhere in Washington D.C., and reportedly cost them an arm and a leg.

There was apparently some discussion about establishing such a “hall” back in the winter meetings before the 1922 season started:

This was no rhetorical device, by the way. This was apparently supposed to be an actual monument:

Of course, since this was an American League Hall of Fame, no National League players could qualify for it:

And then there was stuff like this:

Want to have a fun Hall of Fame debate? Tell somebody that Babe Ruth should have entered the Hall after the likes of John Mitchell and Henry Severeid.

Now, it’s not clear to me that the American League Hall of Fame plaque or memorial was ever actually erected. For example, The Baltimore Sun had this to say about it in early 1926:

Though they claimed that the idea was not abandoned, the thread is really hard to follow after this point — leading me to believe that the idea was indeed abandoned.

Long story short — the Hall of Fame debate is almost as old as the game itself.

Cool look back. It's an interesting point that the notion of a (virtual) "hall of fame" probably predates any physical ones by ages. It might be interesting to try to nail down the first general uses of the term as a metaphor for excellence in anything.

FWIW, I decided a while back that a lot of the debate about who belongs depends on whether one sees the HoF as a shrine to baseball or a museum of baseball. It seems reasonable to exclude, for instance, Pete Rose from a shrine, but equally reasonable to include him (and many others) in a museum of baseball. Perhaps it would be a good idea to have both.

Very nice work. I knew the early MVP selections (starting with the Chalmers award) made previous winners ineligible to win again, but I hadn't thought about the names being aggregated to create a physical hall of fame monument. I knew the Hall of Fame for Great Americans started in 1900, long before baseball's, though I didn't know it had a palatial building. When Cleveland brought up a pitcher named Steve Foster in the 1990s, I wrote that he had a Hall of Fame name -- the 19th-century songwriter (Hard Times Come Again No More, S'wannee River) had been chosen years earlier. The Bavarian building was a surprise to me. I had thought HOFs were an American invention, a product of the fact that unlike Great Britain and much of early 20th-century Europe, people here couldn't be given a noble title. (A Welsh correspondent of mine had no idea what a Hall of Famer was.)