The National Pastime Rosters

I stumbled across this post a few days ago on the Hey Bill portion of Bill James Online:

I know the feeling. And so I’ll be frank with you.

I don’t know everything.

I certainly don’t know everything there is to know about National Pastime. The more I dig, the more confusing the situation gets.

I’ve been waiting to make a post about National Pastime and the things I’ve been finding. I want to thank those who have sent me copies of the cards and some of the documents that came with the reprint of National Pastime by Sports Game Publishing 20 years ago. Your donation and help really is greatly appreciated, and I would absolutely love to hear from anybody else who has taken the time to dive into this game and try to figure out where all of this stuff came from.

I made a mistake in thinking that I could come up with conclusions about something as basic as the rosters before posting. That’s simply not going to happen. Things are a lot more complex than I first thought.

Description of National Pastime Rosters

Let’s start with the easy stuff first.

Each team in National Pastime consists of 18 players, without fail. I believe that Van Beek decided to do this to cut down the cost of printing. My guess is that he printed the cards 9 to a sheet. 18 players per team allowed him to print only 32 sheets of cards.

I’ve seen people speculate that the rosters were small because fewer players were used in 1930. This is not true. The average American League team used 32 players in 1930; the average National League team used 30. Team totals ranged from only 29 players on the Cubs to a whopping 40 on the White Sox.

Now, it is possible that Van Beek might not have had statistics to give cards to a full 27 players per team — but we’ll have to save that speculation for another post.

Anyway, each player card includes one simple position designations: Catcher, Infielder, Outfielder, or Pitcher.

This is what the breakdown looks like:

The first thing you’ll notice is that each team has 5 pitchers. This might be puzzling when you consider that there is no pitching system in the game.

It’s also odd that the White Sox, Phillies, and Senators all have 3 catchers each, and not just 2. In the case of the White Sox and Senators, Van Beek’s decision to card a third catcher is quite strange, actually. But we’ll get to that a little bit later.

Each of the 18 players on each team received a batting card and nothing else. There are no fielding ratings and no pitching ratings. It may seem primitive, but it’s actually pretty remarkable when you start digging into it.

The 1930 Roster Puzzle

And now we’ll get to the point where I honestly am not sure what is going on.

You’ll recall in this post that I argued that Clifford Van Beek could not have used the 1931 Spalding or Reach baseball guides to create the National Pastime cards.

I still believe that he did not use either one of those books. However, there is clear evidence that the cards are based on 1930 statistics — in part, at least.

The evidence lies in the rosters.

It’s actually not too hard to see this. Van Beek gave cards to the players with the highest at bat totals on every team.

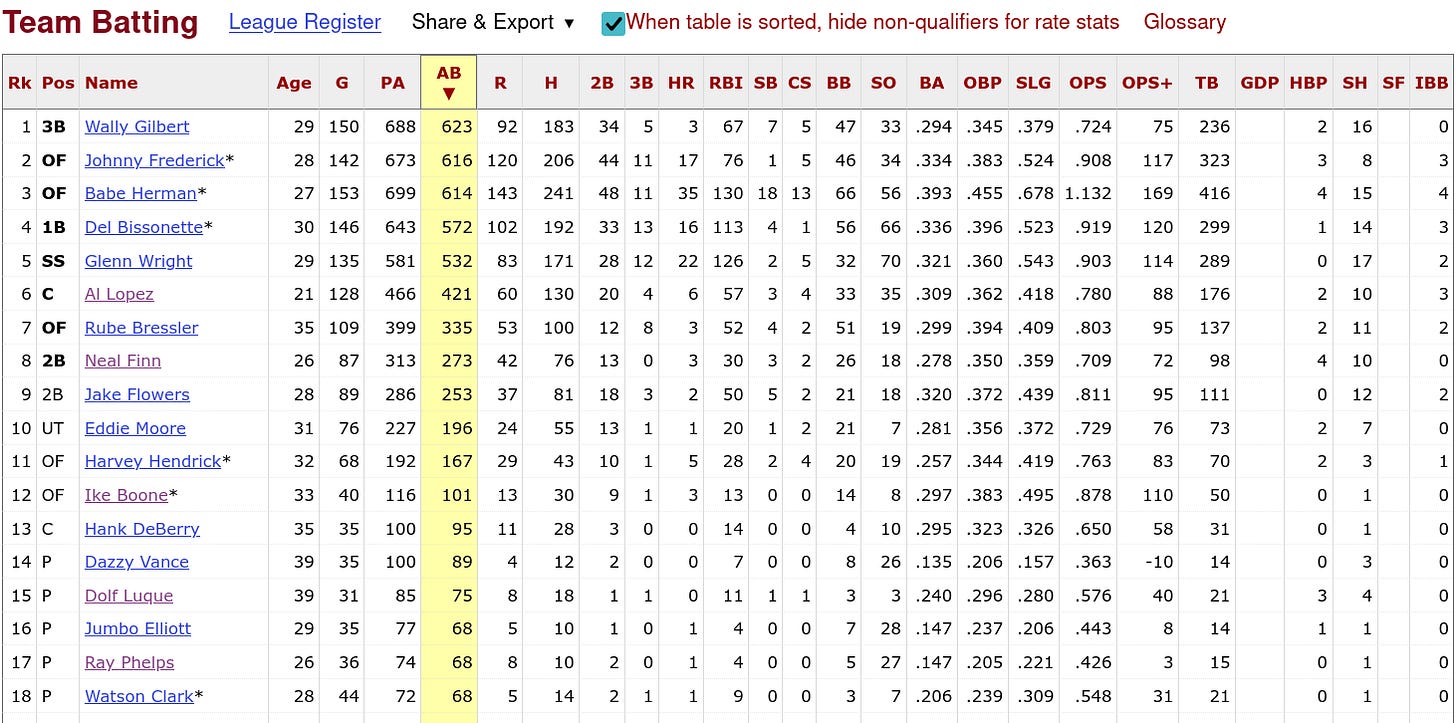

Let’s take a look at a sample team to see how this works. Here are the 1930 Brooklyn Dodger players that Van Beek gave cards to, sorted by their 1930 at bats:

And here are the 1930 Brooklyn Dodgers, sorted by at bats:

As you can see, the players match up exactly. Nobody is left out. The order of the last 3 pitchers is a little bit funky, but don’t worry too much about that. All 3 had exactly 68 at bats that year.

Compare that to the 1929 Brooklyn Dodgers roster, again sorted by at bats:

I went a bit deeper into the list this time to show a point. You’ve got to go extremely deep into the 1929 Brooklyn roster to find the likes of Jumbo Elliott.

Notice the players that are missing, too. Dave Bancroft wound up with the Giants for 10 games in 1930 before retiring. If Van Beek were truly just using 1929 statistics and calling it 1930, you’d expect to see him with a card for Brooklyn: after all, he was the team’s starting shortstop. Bancroft did receive a card for his brief time with the Giants; we’ll talk about that in detail later.

And my apologies for putting these interesting questions on a shelf for now. One of the difficulties involved in wrapping my head around this has been trying to figure out which questions are easy to answer and which ones require more time. The fact that Bancroft received a card for his 10 game, 17 at bat performance — all in May — requires me to explain how Van Beek handled players who were traded during 1930, and that’s going to take a post all by itself.

I’ve been through the rosters of all 16 major league teams, and can assure you that every single key player received cards. A kid purchasing National Pastime in late 1930 or early 1931 would not be disappointed. His favorite players received cards, even if they were pitching for the Phillies.

So where’s the puzzle?

The puzzle lies in figuring out how Clifford Van Beek got this information.

The Baseball Guide Theory

“That’s easy,” you say. “He just used the baseball guide.”

There’s a problem with that. Baseball guides in 1931 didn’t organize players by team.

Let me show you. This comes from a scalled copy of The Reach Official American League Base Ball Guide for 1931, which was very kindly sent to me by a friend on a forum. I’m extremely grateful for the donation, as it has allowed me to address this theory directly.

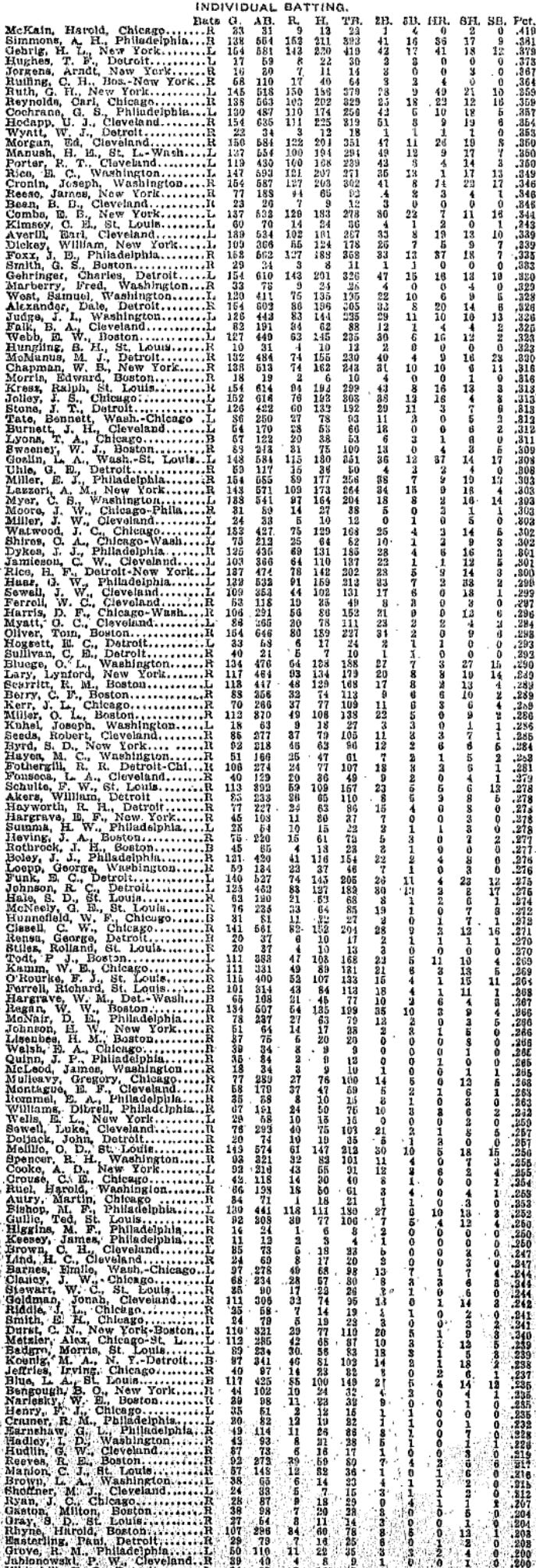

Here are the American League batting records in that guide:

Now, let’s stop everything right here and think about what we’re looking at.

You’ll notice that the players are sorted by batting average (here denoted as “percentage,” or PC). Players are not sorted by at bats, and are not grouped into individual teams. All players who appeared in 10 or more games in 1930 are included.

I don’t have a copy of the 1931 Spalding Guide, but I know that this is the basic pattern that both guides followed over the years. Here’s the American League listing from the 1930 Spalding Guide for the sake of comparison:

Notice that the presentation is exactly the same. The stats presented are the same. And, in fact, the source is the same: both books used stats compiled by the Howe News Bureau in Chicago.

And, if you really want to go deep, here are the American League stats as printed in the December 4, 1931 issue of The Sporting News, which I originally included in this post:

Now, the abbreviated first names make it unlikely that Van Beek used The Sporting News as his source for this information. His cards have first names and last names, not first initials and last names.

But there’s another problem here, one that is hiding right in front of your nose.

The top American League batter in 1930 listed in each of these sources is Harold McKain of the Chicago White Sox.

Now, we know that McKain, a pitcher, didn’t win the batting title that year. He had a remarkably good hitting season for a pitcher, managing a .419 batting average.

You’d think that Van Beek would give him a card, especially since there are rumors that Van Beek was a fan of Chicago sports. Those who shake their heads at him for allegedly using Rogers Hornsby’s 1929 statistics for his National Pastime card usually figure that Van Beek wanted the Chicago teams to get a boost.

McKain, however, did not receive a card.

In McKain’s place, in the 5th pitcher spot for the White Sox, was Urban Faber, who appeared in 29 games but had 49 at bats.

Now, Faber was a starting pitcher, and McKain was chiefly a reliever (and a pretty ineffective one at that). I suppose Faber could have been favored because of his name and because of the 18 extra at bats.

Faber, by the way, hit .041 in 1930. So much for playing favorites.

Skipping McKain in this situation is significant, however, because it means that Van Beek likely did not use this chart as his primary means of choosing players. Not only would he have to deal with the headache of removing players from the awkward listing and reassembling the teams, but he would also have to know at some point in time where he was going to make his cutoff.

Alternatively, Van Beek could have used the fielding record section of the baseball guide, which looks like this:

This doesn’t help much with the puzzle problem, though. These players are sorted by fielding percentage, not by games played — and certainly not by at bats. Players like Tony Lazzeri wind up listed multiple times. And, of course, we need to remember that the fielding designations on the cards consist only of Catcher, Infielder, Outfielder, and Pitcher, with no additional subdividing.

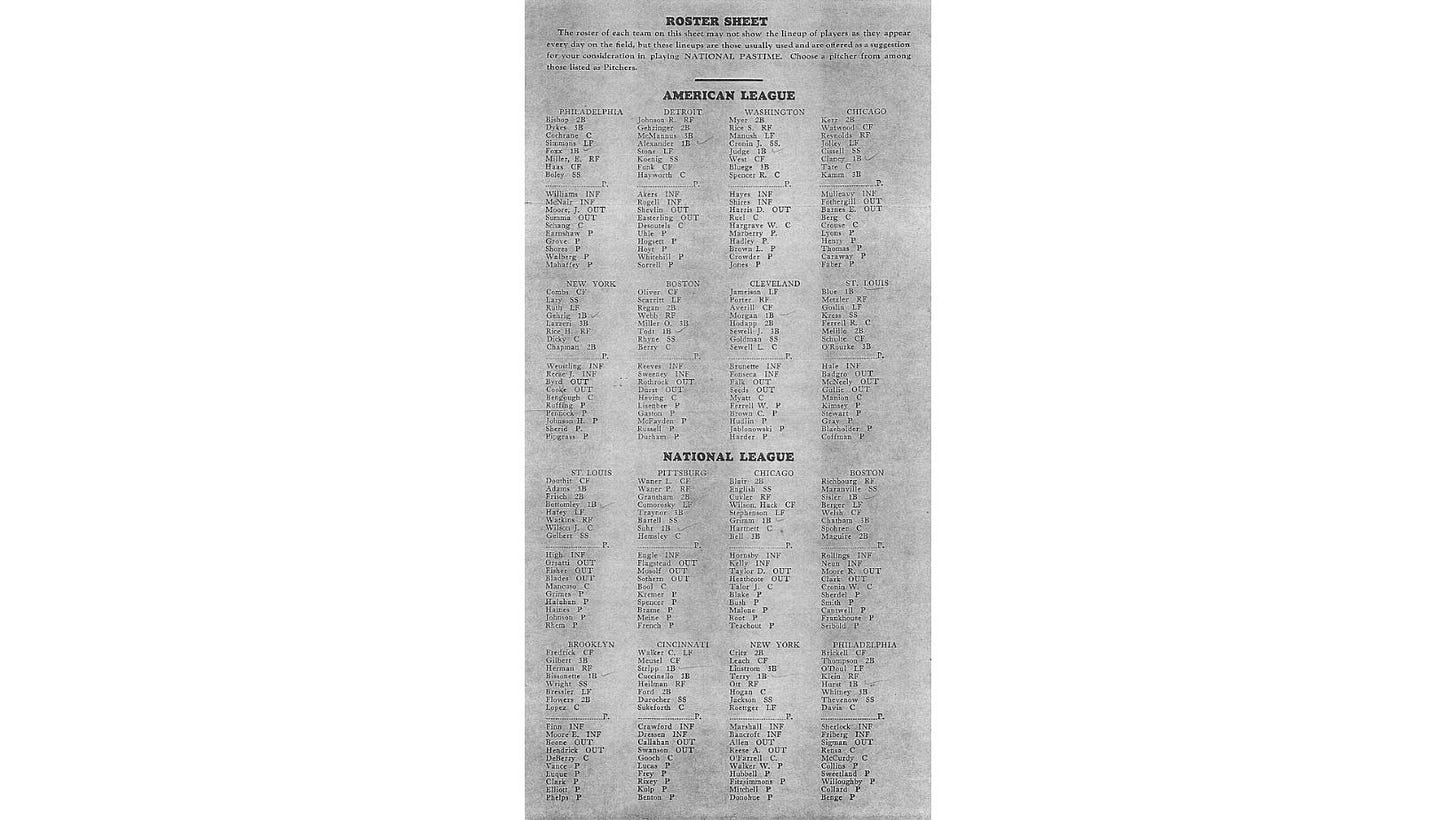

There’s always this page, which I showed you before:

The problem here, though, is that the players are listed alphabetically — and there are certainly more than 18 players per team!

Like I told you, it’s a puzzle.

My Theory

My theory is that Van Beek didn’t use these pages to make his roster determinations.

When we start talking about individual players, we’ll see that Van Beek sometimes made odd mistakes. There is at least one major mistake (there may be more) that indicates to me that he likely didn’t see the American League fielding statistics before National Pastime was created.

It feels a little bit odd to say this, but I honestly think that Van Beek tracked major league boxscores through the 1930 season. I think that is how he came to his roster decisions, and, yes, I think there is enough evidence to show that he played through a sample 1930 season using his patented game engine while the season played out in real life.

We’ll look next time at the biggest piece of evidence I have for this crazy theory: the lineup sheet that came with the game.

Afterwards, we will start looking at a few of the individual players that indicate to me that Van Beek probably didn’t use either of the 1931 baseball guides to make his cards. There are problems with this theory, however, including a number of difficult questions that I don’t quite know the answer to yet.

We’ll have to try to figure this one out together.