The Power-Speed Number

Want to know just how dated Bill James’ ideas are? You’ll see in this section.

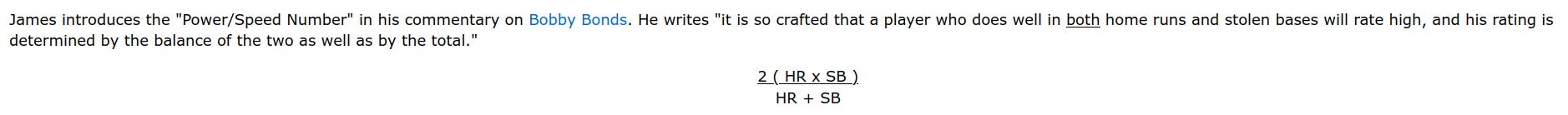

In the 1980 Baseball Abstract, James invented a brand new stat. This comes from his commentary on Bobby Bonds, and the summary comes courtesy of Rich Lederer:

I’ve learned elsewhere that this formula calculates what is called the harmonic mean of both numbers. As that Wikipedia page will tell you, the harmonic mean is usually only helpful when you’re looking at rate statistics, not raw totals. In fact, the examples from this old textbook generally refer to things such as miles per gallon for city driving and highway driving weighted depending on how much of each the driver does.

So why did James decide to use the harmonic mean? Why is there so much interest in combining home runs and stolen bases? And does it matter?

Well, unfortunately, I don’t know why he used the harmonic mean among all the possible measures he could have used. In fact, using only stolen bases seems like a pretty poor measurement of actual speed. I presume that James wanted a quick and dirty way to help players who had both good power and good speed to stand out above all the rest — and players with both good power and good speed were actually pretty rare in the late 1970s.

It makes sense that James would come up with this stat in the context of Bobby Bonds. Look at Bobby’s career statistics:

Bonds was a power hitter who could steal 40 bases a season pretty much no matter where he played. I suppose this statistic was James’ way of trying to say that the 33-year-old Bonds was actually pretty good in Cleveland in 1979: 25 home runs and 34 stolen bases aren’t all that bad.

Of course, James forgot to mention the 23 times caught stealing, which should have been a big red flag.

And that’s one of the big problems with stats like this. Players can easily game these statistics, especially if they are uniquely proficient in either stolen bases or home runs.

The Wikipedia page on the Power-Speed Number explains the all-time leaders:

Now, the problem with this metric is that there are easier ways to figure out who these guys are. Acuna was famous for joining Jose Canseco’s old 40/40 club in 2023, and Ohtani is well known for being the only member of the 50/50 club.

And then you have Barry Bonds and Rickey Henderson, who represent different extreme examples of why this statistic is utterly useless. 514 stolen bases is impressive, sure — but Bonds gets a bump for hitting more home runs than anybody else. And the fact that Rickey “only” hit 297 home runs is disguised by his all time high total of 1,406 stolen bases.

That leads us to the ultimate problem with this statistic: it simply doesn’t tell us anything worth knowing. We know that power is about more than just home run hitting. Deadball era players and players in extreme ballparks (like the Astrodome) are at a natural disadvantage. Meanwhile, we also know that speed is about more than just stealing bases — and, as we can see with Bobby Bonds in 1979, being caught stealing actually makes a difference.

It’s a cute statistic, but there’s no clear explanation for why it is what it is, it doesn’t tell us anything worth knowing, and the final numbers are manipulated by extreme outlier performances. In other words — this is a stat we really shouldn’t bother with.