The Seitz National Pastime Homebrew Cards

Searching for the connection between National Pastime and APBA

The Seitz National Pastime Homebrew Cards

First of all, a big thank you to the readers who contacted me with scans and copies of the J. Richard Seitz homebrew National Pastime cards.

If you don’t know much about Clifford Van Beek’s National Pastime game, this blog is probably the right place for you. I’ve written about this 1930 tabletop baseball sim a few times over the past 2 years. I created this page a while back, hoping that it would serve as a sort of index to related articles:

However, I’ve been too busy trying to draft new articles to keep that page updated, unfortunately.

I recommend checking out this video I made a little while ago if you want a basic history and overview of the game itself:

Now, the part that I don’t talk much about in that video is the direct link between National Pastime and APBA. There is a link, and it becomes more obvious the more you dig in.

We’re going to take another step in that direction today.

J. Richard Seitz was 12 years old, going on 13, at Christmas 1930. I presume (though I have no proof) that Seitz asked for a copy of National Pastime for Christmas. He was born on February 18, 1918, so it’s also possible that Seitz might have received a copy of the game for his 13th birthday, on February 18, 1931.

Whatever the occasion was, we do know for a fact that he had a copy presumably before spring 1931. We know this because he and his friends started their own draft league, the American Professional Baseball Association (A.P.B.A.), in 1931.

We know that it started in 1931 because we’ve got copies of their league files. Well, a collector in the community has the originals, that is. An article by Scott Lehotsky in the January 1997 issue of The APBA Journal gives us our confirmation:

Now, I don’t have a copy of those notebooks, nor do I know of any scanned copies. If you happen to be the specific collector who has these, and you are willing to figure out a way to scan them and preserve them for posterity and for history, please contact me.

Seitz loved National Pastime. He liked the game so much that he sent numerous letters to Clifford Van Beek’s Major Games Company requesting new player cards after the end of the 1931 season. I’m not sure if Van Beek ever received the letters, but I do know for a fact that the Major Games Company went bankrupt in early 1932 after being sued by its printer for an unpaid debt:

Seitz must have been crestfallen to hear nothing. He got over it in the end, though, and, at some point in time, Seitz decided to make his own National Pastime cards.

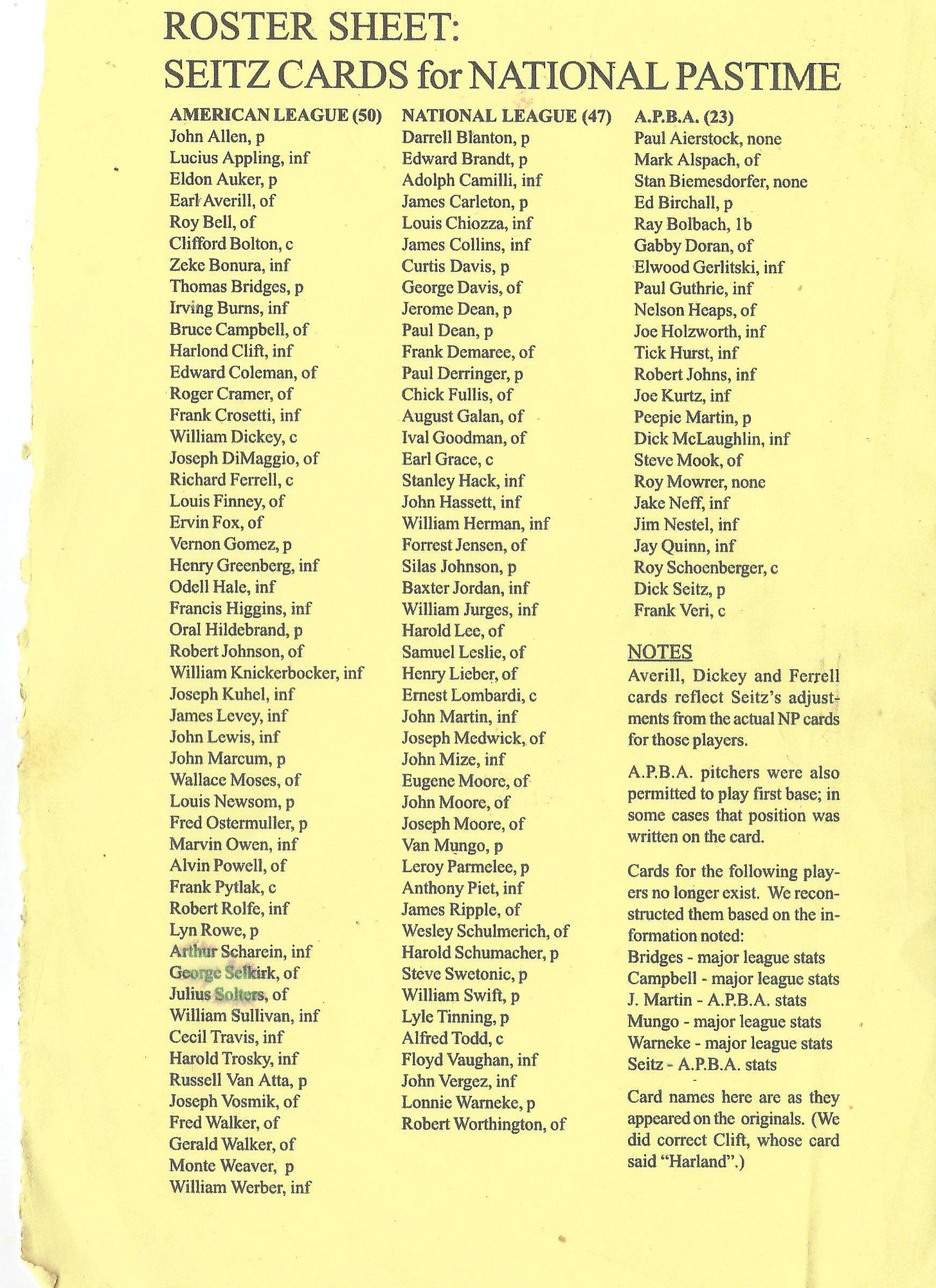

Now, the coolest part of all is that we have copies of a big chunk of the cards Seitz created. And, thanks to the community, I now have scanned copies of the reprints of all the cards we know about — all of which are listed in this helpful checklist:

I wanted to do a preliminary look at these cards and how they were created. Now, I was only interested in looking at the cards I know that Seitz created. In other words, I excluded the 6 “reconstructed” cards from this minor study.

There’s some pretty interesting stuff going on with the Seitz cards. First of all, this is the distribution of play result numbers (1-41) in the Clifford Van Beek originals:

Van Beek was really fond of giving out play result number 40 for some odd reason.

Anyway, here’s a similar chart for the 114 J. Richard Seitz homebrew cards (as in all the cards we know are originals, ignoring the reconstructions):

Those charts will probably boggle your mind a bit, so let’s look at a few individual play result numbers. First, let’s look at the hit numbers (1-11):

I suppose we could conclude that a bunch of the cards Seitz created were for star players, which might explain why a greater percentage of the hit result numbers were for the power numbers (1 through 6).

Still, there are some things that jump out at me. For example, Clifford Van Beek seems to have treated play result number 8 as the most common base hit number. Seitz tended to favor 7, and seems to have done so in a significant manner.

Seitz also was extremely fond of play result number 3. Now, I don’t know this for sure, since I haven’t really dug into all the data yet, but I suspect that the Seitz National Pastime homebrew cards contain a greater share of play result numbers 3 and 4 than any APBA or National Pastime set ever created.

Now, there does appear to be some evidence in all of this that Seitz might have just used existing National Pastime cards to serve as a guide for his own creations.

For example, in the National Pastime world, 100% of all instances of play result number 23 come from pitcher’s cards. There are 80 23s in all, and 80 pitchers in all: every pitcher has exactly one 23. We see the same pattern in the Seitz homebrew cards: the only players who have play result number 23 are pitchers. All pitchers have one, with the exception of 4 of the APBA manager fictional cards (three of which technically don’t have a position listed on their card), and the card for Darrell Blanton:

Seitz, however, then breaks the pattern with play result number 22. All pitchers in National Pastime have at least one 22 on their cards. However, only 14 of the 28 pitchers in Seitz’ homebrew cards have a 22.

I’m not sure how significant this is. It’s at least a sign that Seitz might have been creating his cards from scratch after studying what Van Beek did, rather than just copying an old pitcher to create a new one.

The other fascinating thing is play result number 35. At some point in time, Seitz started to give play result number 35 on dice roll 65 to every player. Van Beek tended to only give that result 35 on dice roll 65 to left handed and switch hitters, as we saw here:

No fewer than 71 of the 114 Seitz creations have a 35 on dice roll 65.

Unfortunately, we don’t know for certain when Seitz created each of these cards. I suspect, though, that he may have defaulted to certain dice roll locations for out play result numbers as time went on.

We’ll talk more tomorrow about what a “model” Seitz card might look like, and how it would differ from what Clifford Van Beek did.