The Signing that Almost Destroyed the Pennant Race

The forgotten 1900 Topsy Hartsel controversy

The Signing that Almost Destroyed the Pennant Race

We’re really reaching into the depths of obscurity to fish this one out.

If you’re bored enough, you might find this paragraph from the SABR biography of Topsy Hartsel:

Now, I don’t want to be too critical of the SABR biographies. However, every once in a while the biographers downplay incidents that were actually quite significant. You’d probably wonder why anybody cared about the horrible 1900 Cincinnati Reds being forced to forfeit a number of games in late September 1900. Well, it turns out that it mattered a whole heck of a lot — and yet most people have forgotten the story.

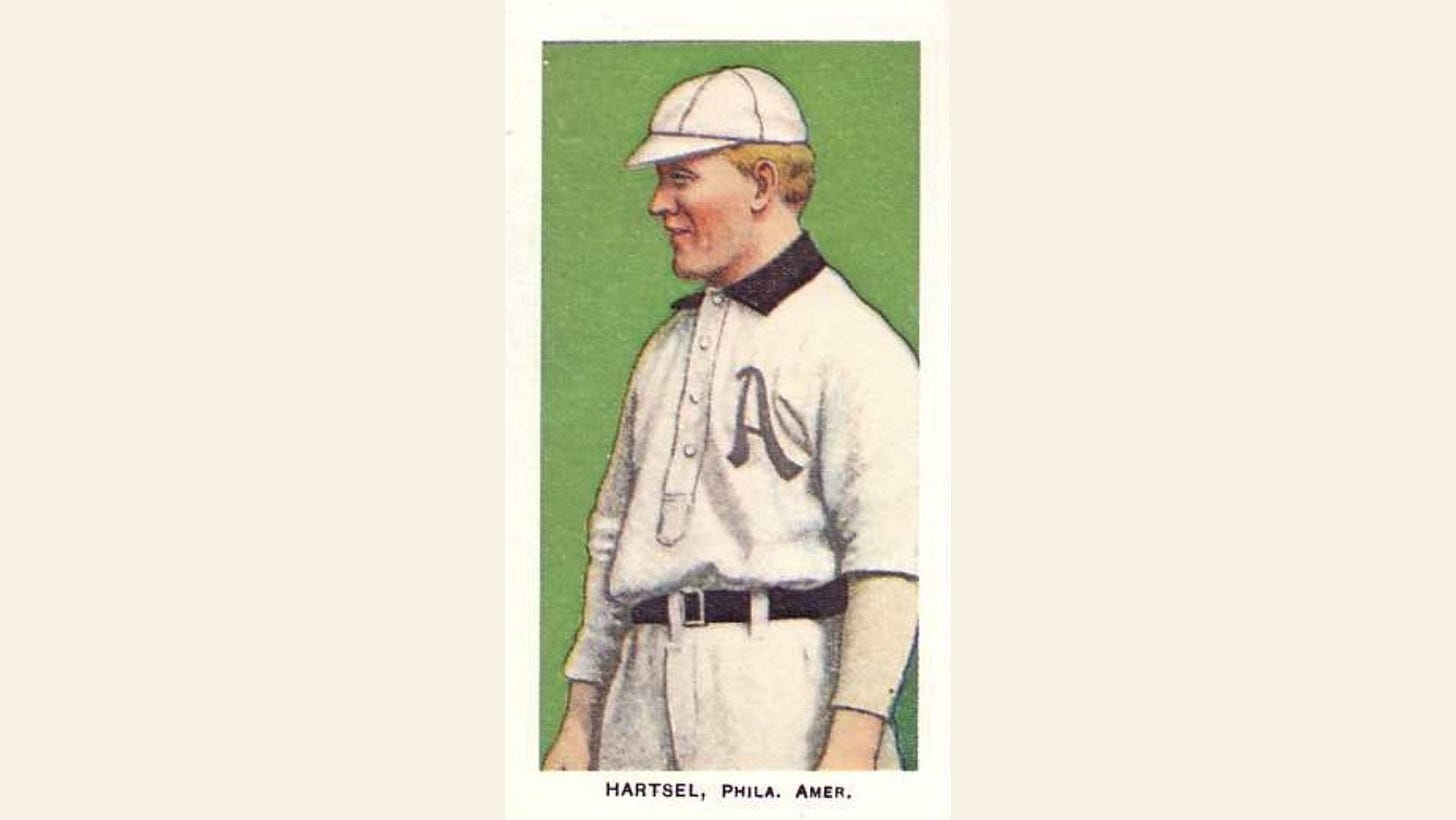

Hartsel

Hartsel came up with Louisville in 1898, but saw only limited play in 1898 and 1899:

Per that same biography, he was sold to Indianapolis in the old Western League in the summer of 1899. Even with the rise of the Western League to the American League and the controversy over whether we should consider it a “major league,” Hartsel remained pretty obscure. He was a castoff from a team that no longer existed, a player who seemed like a one-month wonderkid who didn’t have real major league talent.

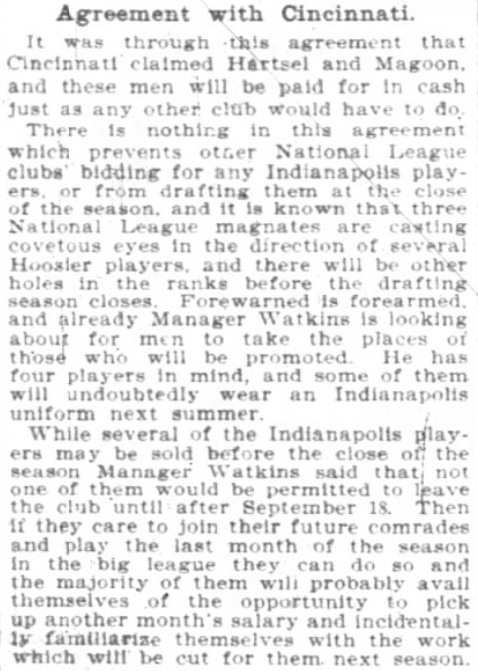

However, as the story goes, Hartsel was sold by Indianapolis to Cincinnati at some point in time in July 1900.

This is where things become confusing. I can’t find any primary evidence of this transaction at all. The earliest source I could find about Hartsel potentially moving to Cincinnati comes from The Indianapolis News on August 20, 1900.

I’m going to quote this entire article, since there is a bit of background context that we need to go through.

Syndicate Ownership?

We don’t talk a lot about this stuff these days because of how squeamish it makes us feel. Nobody likes to think of direct syndicate ownership. Heck, most of us like to think of minor league teams as part of a larger organization designed to move players to the front, and not as some sort of monopolistic collection of ballclubs under the rule of a single man.

Now, I’m not aware of any good sources on Brush’s apparent ownership of the Indianapolis club in the old Western League, aside from this article. His SABR biography makes absolutely no mention of the controversy we’re talking about here, and the closest thing I could find from his Wikipedia page is this tidbit about how he many have caused Ban Johnson to become American League president:

The irony, of course, is that Brush was one of the men who bought out the Baltimore Orioles in 1902, stripping it of its good players and nearly bringing the American League to ruin. But I’m getting way ahead of my self now.

I’ve got to believe that the animosity between Brush and Johnson wasn’t all that strong in the olden days — certainly not if Brush owned the Indianapolis team up to 1897. At any rate, the claim in this article is that Cincinnati had first dibs on any and all Indianapolis players after the 1900 season as a result of some sort of business arrangement.

American League Muscle

Now it’s time to go back to my favorite hobby horse: the major league status of the 1900 American League.

The American League was a strong enough league at that time to prevent National League teams from placing its players on their rosters before the end of the 1900 season.

American League teams could sell players to National League clubs before then. However, they couldn’t leave until the American League season ended on September 18.

I know that this seems like a minor point. However, it’s really worth stressing. The American League did not have a subservient relationship with the National League in 1900. This wasn’t your classic farm system arrangement. In fact, as we’ll see, even this buddy-buddy deal between Cincinnati and Indianapolis was in question.

Chicago’s Claim

Okay — now this is where it gets weird.

The Chicago National League club claimed that it also had a claim to Hartsel, and that its claim predated Cincinnati’s claim.

The claim that President Hart of Chicago makes here is that there was some sort of secret arrangement between him and the American League that entitled him to the pick of the American League players in exchange for allowing an American League team to tred on his territorial rights.

In other words, we’ve got two competing secretive claims going on at the same time. Cincinnati claims that it had first dibs on any Indianapolis player due to some sort of secret relationship between the two clubs. Meanwhile, Chicago claimed that it had dibs on the player due to a separate relationship between itself and the entire American League.

Sounds like a lot of shouting over a man who hit .240 in half a season the year before!

Off to Cincinnati

Despite Chicago’s claim on him, Hartsel promptly signed with Cincinnati as soon as the American League season ended:

Hartsel indeed started playing with Cincinnati that September, which is what led to all the trouble.

The Pittsburgh Series

Cincinnati went into Pittsburgh for a crucial series starting September 26. At the beginning of that series, the standings looked like this:

The Pirates were only 1 game behind Brooklyn at this point, and were hosting the 7th place Reds, who had been awful all season long.

And, well, this happened:

Pittsburgh lost 4 of 5 from the Reds, spoiling their chances at a pennant. The Pirates did well in their 8 remaining games (remember, there were only 140 games in a season back in 1900), but it was too little, too late.

But, of course, that wasn’t all.

The Controversy

The best reporting on this I could find was, ironically, in the Brooklyn newspapers.

Now this is the part where it gets really interesting:

If you read this carefully, you’ll see that the proposal was to completely invalidate all 5 of the games that Hartsel played in for Cincinnati against Pittsburgh. That would have put Brooklyn at 77-52 with 11 games left to play and Pittsburgh at 73-54 with 9 left.

There’s a problem there, of course. One wonders why the league would not instead change all 4 Pirate losses against Cincinnati into forfeit victories. After all, if it were discovered that Cincinnati didn’t actually have the right to sign Hartsel, it would only be fair to turn the wins it enjoyed with him on the team into losses.

If that were the case, Pittsburgh’s record would have been 78-50, 1 1/2 games ahead of Brooklyn, again with only 9 games left to play.

And that’s where the pennant race would have really become controversial.

There’s more:

Now, I think the wording here is incorrect. If Chicago were allowed to pick 2 men from each American League team at the end of the season, it would have potentially signed 16 new players — the size of an entire active roster at the time. I believe that the agreement (if it actually existed — I haven’t seen much actual evidence of this) would probably have allowed Chicago to sign 2 players total, not 16.

There’s also the question of the “Wrigley” case. This refers to Zeke Wrigley, who played briefly for Brooklyn in 1900 — and whose games were all thrown out of the official record. We’ll have to save him for another time, as this article is long enough already.

Oddly enough, I’ve been unable to find any further references to this controversy at this time in any other newspapers. It seems to have been ignored by the Pittsburgh newspapers I have access to. The Cincinnati Enquirer almost certainly had coverage of all this (it was easily the best baseball newspaper in the country in 1900), but, sadly, the relevant pages are completely faded away and unreadable.

The End

And, well, the controversy ended there.

Once the pennant race was officially over, the National League simply awarded Hartsel to Cincinnati:

In other words, the American League owners concluded that Hartsel should have gone to Chicago at the start of the 1901 season after all.

Note as well that the practice of “farming” players out preceeded Branch Rickey by several decades. It was already fairly well established by 1900.

I’m not entirely sure what the National League owners decided in the end. At any rate, they allowed those pivotal 5 Cincinnati - Pittsburgh games to stand, thereby avoiding a controversy that would have certainly put the league in even more trouble.

There is no mention of this controversy in either of the 1901 baseball guides — at least, not that I could find. Again, this is in stark contrast to the Zeke Wrigley controversy, which had absolutely no bearing on the pennant race of 1899 in the end. There was a clear precedent to wipe out the contested games; however, the National League decided to simply do nothing.

And, in the end, most of us have completely forgotten about the signing that almost destroyed an entire pennant race.