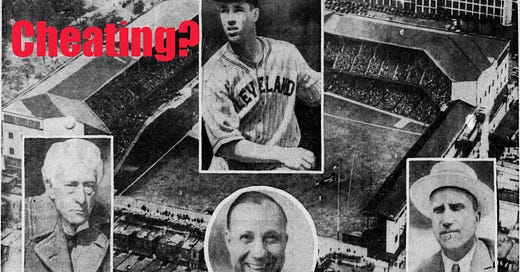

The Sketchy Signing Of Bob Feller

I was reading the 1937 Spalding Guide for fun today.

Okay, I know, I know — that makes me a geek. I’ll admit it.

I was actually looking through the guide for something completely different — another project tangentially related to this article.

I came across this:

If you don’t want to read all of that, let me summarize.

Bob Feller became a legend in 1935. He was 16 or so, and he was striking out everybody. And when I say everybody, I mean everybody.

The newspapers in Des Moines, Iowa picked up on him. This game, though, was absolutely the one that put him on the map:

Striking out 18 men in a semipro game is not the same as striking out major league hitters. However, this kind of performance was taken quite seriously, and major league scouts started to flock to games played by Farm Union and other teams.

The funny part, though, is that Feller had already signed with Cleveland.

Feller reports that he signed with Cleveland for $1 and an autographed baseball:

None of that is disputed. It’s a historic fact.

The problem, however, is that Cleveland wasn’t allowed to do that.

As I understand that Spalding Guide article, as well as contemporary Associated Press reporting, the problem is that there was a rule prohibiting major league clubs from scouting sandlot players directly.

Now, if you’ve done your reading, you know already that this happened all the time, rule or no rule. Connie Mack was famous for finding sandlot players and semipro kids and giving them trials. The 1919 Philadelphia Athletics had the record for most roster players for years, the vast majority of whom were Mack’s famous trialists.

The problem here isn’t that Cleveland broke the rules. The problem is that the Des Moines minor league team made a big stink about it — after Feller started to pitch in the majors, that is.

The way that most clubs got around the prohibition on amateur scouting was to “recommend” that a loosely (or even directly) affiliated minor league team sign a youngster. In practice, the team would sign young players and assign them to minor league teams under the control of the franchise — sort of like The Godfather sticking you in Clemenza’s regime.

However, Cleveland was a bit too direct. Cy Slapnicka, the scout who signed Feller, signed him directly. Cleveland should have given him a position with the Fargo-Moorhead Twins, the team Feller was assigned to. Slapnicka could have then claimed that it was actually the minor league team that signed Feller, not the major league team, and Des Moines would have had no legal reason to complain.

As it stood, Des Moines got $7,500 out of the deal without even scouting Feller. Feller, meanwhile, pitched high school and semipro games in 1935 despite having signed with Cleveland, never played a game in the minor leagues, and went straight to the Indians as soon as the school year was done in 1936.

The Real Story

But that’s not the real story here.

The real story is the death of independent baseball.

We’re going to get deeper into this in the coming weeks. What was really happening here was a form of baseball colonialism. Major league teams turned the minor leagues into a sort of vassal state, a group of “small town” colonies that produced baseball talent without receiving much in return.

And that system exists to this day.

Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis was an awful man. He was racist, he was crooked, and he was probably one of the worst judges in United States history.

However, he was also one of the few men in baseball with any real power who was fighting against attempts to turn the minor leagues into colonies of the major league powers.

And Commissioner Landis, the man who was supposedly untouchable, lost that battle.

More to come.