Third Time Through The Order Syndrome

If you’ve been paying attention to sabermetrics over the past few years, you’ve probably heard of this one already.

In fact, even if you haven’t been paying attention like you should have (and I honestly fit into that category), you’ll hear about this anyway. Anytime you get in a kind and peaceful discussion with other baseball fans on Twitter or Facebook or Notes or wherever, you’ll run into people telling you that complete games aren’t realistic. After all, hitters do a lot better the third time through the order.

A quick Google search brings up this 2018 blog post. And, sure enough, the OPS+ numbers tell the tale. The third time a pitcher goes through the order, he’s a lot more likely to be lit up than the first two.

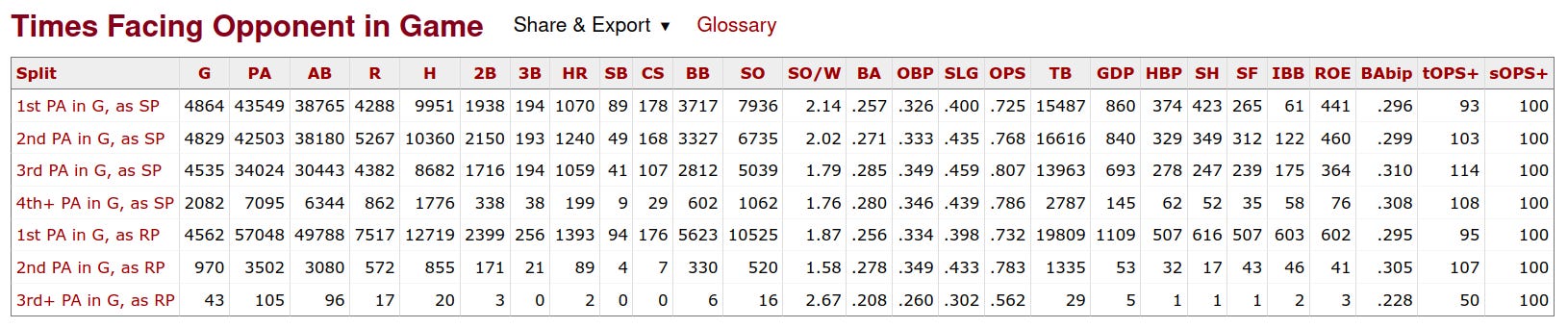

Of course, I don’t need to actually quote anybody. I can just show you the stats. This is how things were in 2024:

Pitchers do pretty well the first time through. The OPS jumps up a bit for each hitter’s second plate appearance. And then, once you hit the third time, the OPS totals go through the roof. As you can see, relief pitchers are subject to the same rule — though I’m having a hard time understanding why you’d let a relief pitcher go through the order for a third time.

Note that I got this from Baseball Reference’s 2024 pitching splits page. And you can do this for almost any season in baseball history, except for the ones where our play-by-play data isn’t good enough.

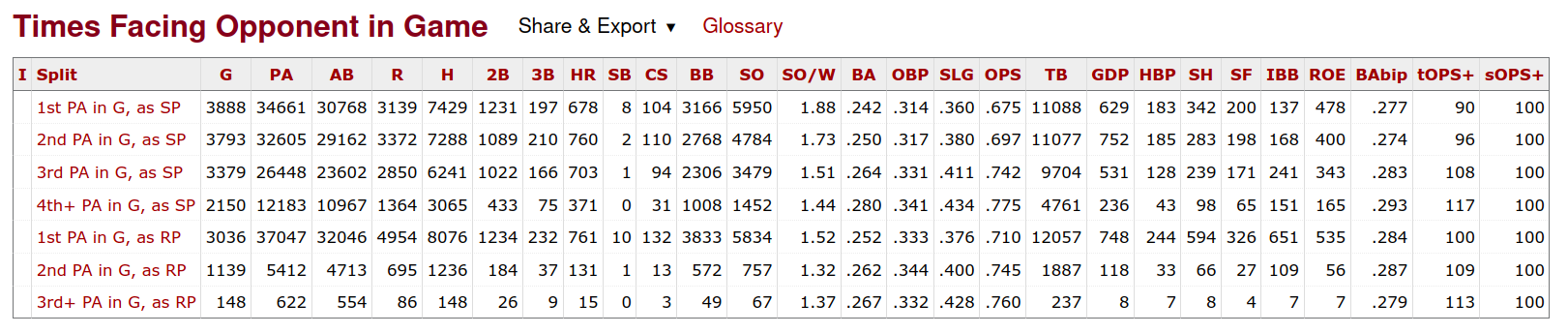

Most modern seasons follow this pattern. Crazy seasons like 1998 make it obvious:

Give a man in 1998 a third crack at the same pitcher, and suddenly everybody looks like Sammy Sosa and Mark McGwire.

You can see this pattern with older seasons, too. Check out 1970:

Even in that year of complete games (852 of 3888 starts were completed in 1970, or a hair under 22%), hitters in general looked like all stars once they got to the third time in the order.

However, there’s a problem.

Keep going backwards, and you’ll see the trend start to die off.

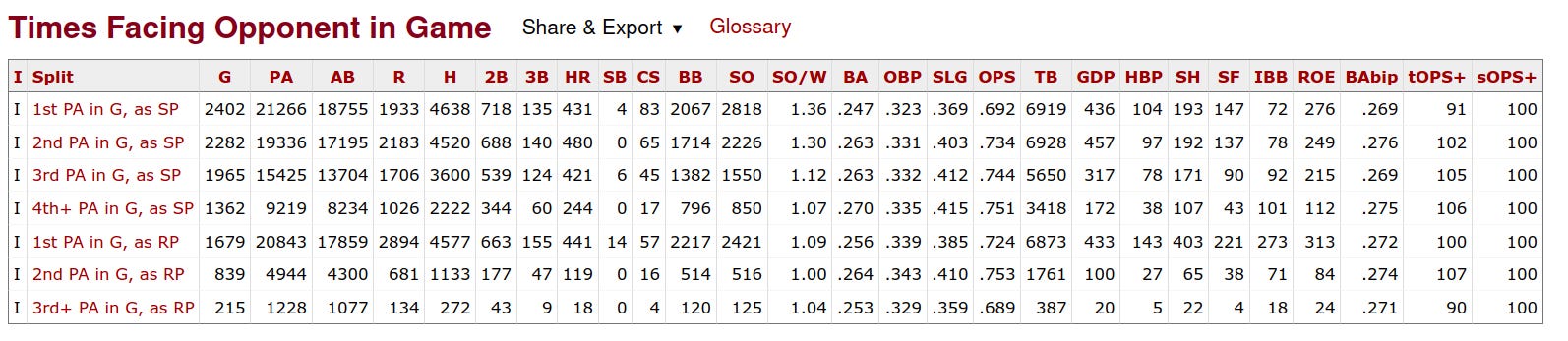

Look at 1955, for example:

There’s still a case of Third Time Through The Order Syndrome here, but it’s not as obvious. There’s a slight uptick in OPS and slugging percentage, but it’s not as obvious as what we saw before.

Now, let’s go back to a really old season. How about 1932?

Yep, that’s right. OPS went down in 1932 as pitchers got to the third time in the order.

Look at 1927:

The syndrome is kind of here — but just barely. Actually, though I’m not a statistician, I’d hazard a guess that there is really no statistical significance here. The jump from a .731 OPS to a .734 OPS is probably just statistical noise. And, while there is some indication that pitchers struggled a bit by the fourth time through the order, it’s still nowhere near as obvious as what we see in modern seasons.

Look at 1916:

It’s like a disappearing act. The further back in time you go, the less obvious it is that there even is a Third Time Through The Order Syndrome. Once again, things hop up a little bit when you hit the 4th time, but not that much. It’s only long term relief pitchers who show notable signs of tiring.

The oldest season we’ve got this kind of data for is 1912:

And, yes, you saw correctly. If anything, pitchers were better the third time through the order than the first time through in 1912.

So what’s going on? Were hitters just bad in those days? Were pitchers superhuman? Or is something else happening?

Well, I don’t quite have the data to back this up, but I think I know what is going on.

It’s all about ballpark shadows.

You already know that there were only day games back in 1912, right? However, you probably don’t realize what time those day games generally started.

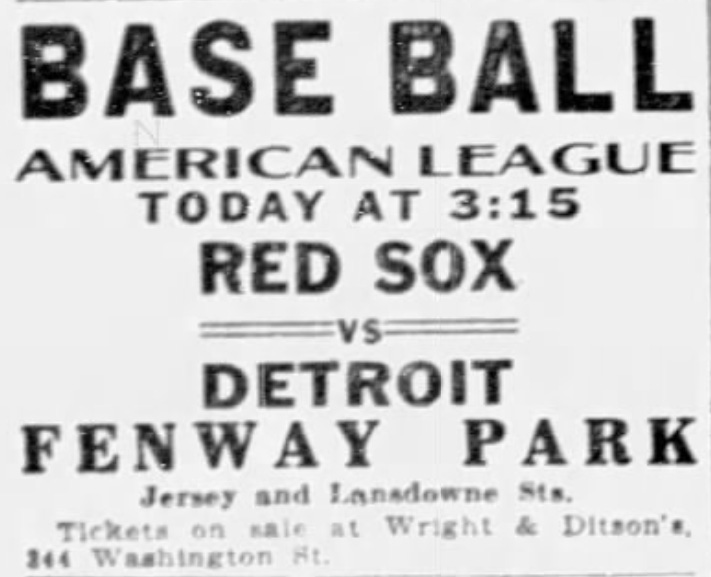

On Tuesday, July 16, 1912, the Boston Red Sox hosted the Detroit Tigers. That game began at 3:15 PM:

On June 10, 1932, the New York Giants hosted the Cincinnati Reds. The Brooklyn Dodgers also were in town that day, hosting the Chicago Cubs. The Giants game started at 3:15; the Dodgers game started at 3:20.

Afternoon starting times between around 3 and as late as 4 were common in those days. In fact, they were so common that many teams didn’t bother to announce the starting time of that day’s game in the newspaper.

Most doubleheaders I’ve seen from that era started around 1 PM. Occasionally you’d see double entry doubleheaders — this was common for scheduled doubleheaders on holidays, for example. That sort of schedule would allow for a game to be played in the morning, though it was pretty rare.

The 1927 New York Yankees, perhaps the greatest team ever assembled, played a crazy doubleheader at Boston on September 5, a Monday. The Yankees lost the first game in 18 innings 12-11, and came back to win the second game in 5 innings, 5-0. The second game was called due to darkness, of course — and it had to be played. The Yankees had another doubleheader at Fenway on September 6, as well as one more game on September 7th, which was their travel day back to New York.

The first game of that September 5 doubleheader started at 1:30 PM:

It was already past 5:30 when the second game started, which is why it’s a miracle they even got 5 innings in. Remember that there were no lights at all in those days.

The 1927 Red Sox were in dead last place and were sinking like a brick in the ocean. Still, more than 34,000 people jammed Fenway Park. The surprise Red Sox victory was such big news that it made the front page:

And we got one of those great cartoons:

More on that absolute classic here:

Now, let’s jump up to 1955. The Brooklyn Dodgers hosted the Milwaukee Braves on June 2, a Thursday.

However, 1955 was in the era of lights, and was a post-World War II season. And so, even though it was a day game on a work day, the Dodgers didn’t start playing until 1:30 PM:

So what?

It’s simple. Visibility was better in the later seasons.

If you were up against Walter Johnson for the third time through the order in 1916, you probably couldn’t see the ball. Everything was dark.

In fact, if you were up against any pitcher from the beginning of the professional game up to sometime in the late 1930s, you were likely going to have to deal with shadows on the field. That’s simply the way things were. Nobody thought it was odd.

Teams could have started each game at 1:30 or 1:00, sure. But they weren’t going to. They were in the business of making money, and their best customers were at work until 3 or 3:30 or so. In fact, in New York in 1908 it was custom to push the start of games back to around 4 in the summer in hopes of attracting fans from Wall Street.

This is of vital importance, by the way. This is one of those facts of baseball history that have gone completely ignored over the years.

Complete games aren’t just a result of certain pitch counts. Complete games also have a lot to do with the playing conditions.

Batters were likely more interested in simply putting the ball in play as the afternoon wore on. That’s why you see decreasing strikeout rates in the early years. Getting any wood on the ball was preferable, since we needed to go home.

I strongly suspect that foul ball rates were likely lower as the game went on, and that pitchers were likely able to let up a bit, relying on the eagerness of the hitters to get them out of any jam.

Now, this is not a general baseball history of sabermetrics blog. We talk about baseball simulations on this blog, first and foremost. And here are a few things I’ve noticed about our beloved baseball sims:

Despite the advances of sabermetrics, most games still don’t do Third Time Through The Order Syndrome right. It’s clear that it has an impact, and it’s something that really should be part of any season going back to something like 1939.

It’s also clear that pitch count fatigue does not explain pitcher stamina in older seasons. It’s far more likely, in my mind, that coming darkness and the shadows of the field had a lot more to do with a pitcher’s ability to finish the game than anything else.

No game I’ve seen has satisfactorily answered the cross-era implications created by this problem. Or, in other words, what happens if Ed Walsh tries to pitch in 1998?

What do you think? Is there something here? Or am I exaggerating the point?

I say leave the starter in. I want to see Paul Skenes face Aaron Judge in the bottom of eighth with the bases loaded and a tie game. Analytics be damned, I want to be entertained.

Good and interesting thought Daniel about stadium shadows impacting hitter performance in older ballparks. Tiring pitchers may have seen an offset there.