Unraveling National Pastime

Clifford Van Beek’s National Pastime game is unique. It’s design is actually more complicated than the games that have come since.

Other baseball games take each player’s batting (or pitching) results and break then down into cards. The results on each card are the same no matter what the base situation is. Think back to the Joe Morgan and Luis Tiant example from last week: the results will be the same no matter what the base situation is.

National Pastime is situation dependent. The player rolls two dice, which give a play result number located on the hitter’s card. That play result number gives a different result depending on which situation is at hand.

And that makes the game very difficult to take apart.

You’ve got two things happening at once. You’ve got player performance, which has been translated into a matrix code of play result numbers. However, at the same time, you’ve got the boards themselves: boards that have nothing to do with National Pastime’s “dice baseball” predecessors, boards that Van Beek created on his own.

And those boards are really interesting.

National Pastime Plate Appearances

We’re going to take baby steps as we try to take the boards apart. We’ll start off first with the plate appearances that each play result number results in. We’ll then look at the number of at bats that come from each number.

Why do this? Simple: because there are patterns. Those patterns are actually quite interesting, too. I believe they give us insight into Van Beek’s thought process.

Now, I really doubt that Van Beek thought much in terms of plate appearances. I think his biggest concern was getting the batting averages right. I believe he knew that players needed to walk, and that walks didn’t count as at bats in terms of batting average. But we’ll get to walks a little while later.

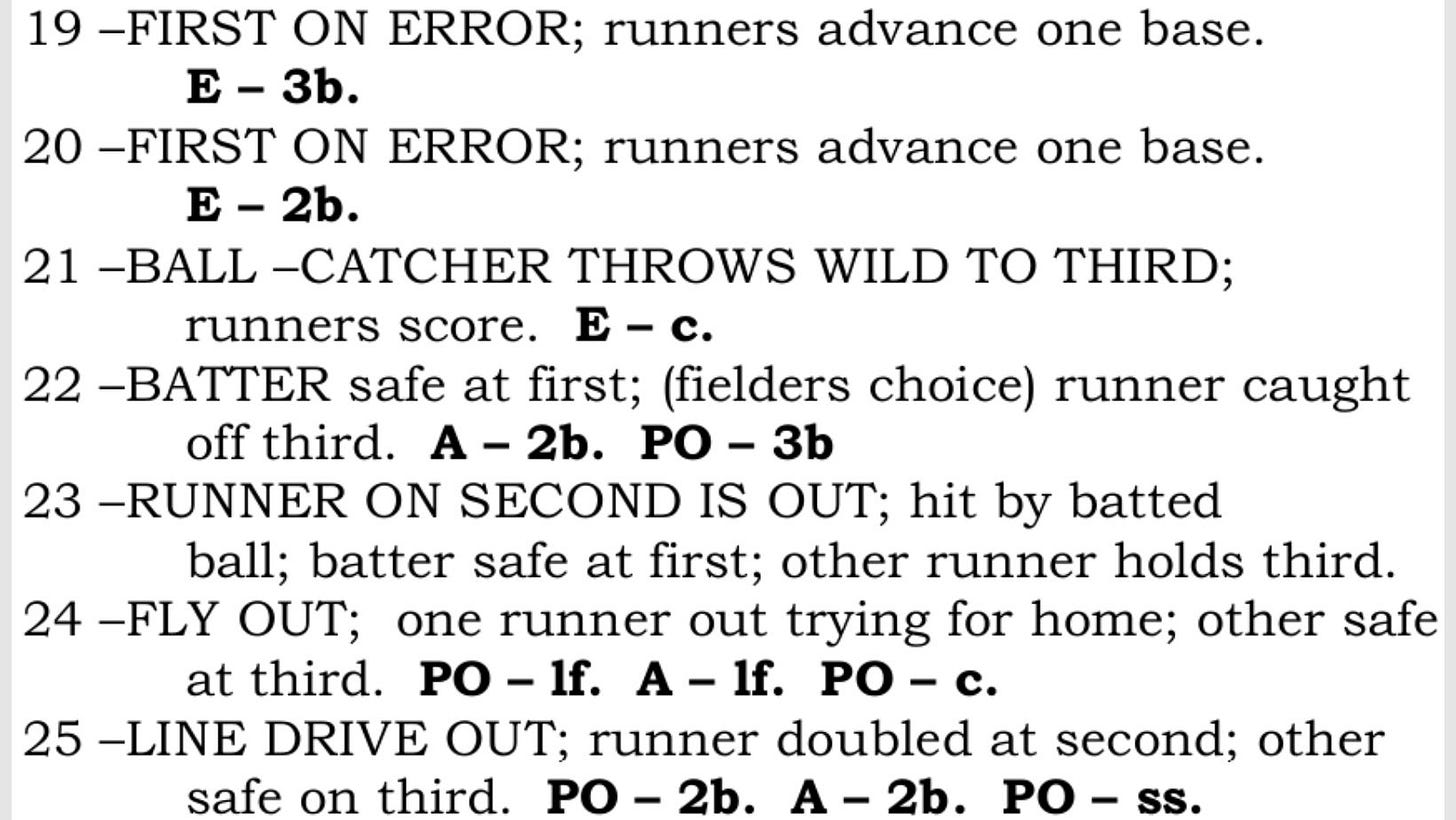

Every play result number will result in either 1 plate appearance or 0 plate appearances. And this is how it comes out:

You’re probably wondering what those columns along the top mean. Here’s the key:

A: None On Base

B: Runner on First

C: Runner on Second

D: Runner on Third

E: Runners on First and Second

F: Runners on First and Third

G: Runners on Second and Third

H: Bases Full

I’m going to use that key from here on out, since it’s easier than writing the text out over and over again in these spreadsheets.

Now, when we look at this chart, we don’t really see much. Play result number 36 is the only one that never results in a plate appearance. 23 (infamous for rainouts) comes close: it results in the runner being hit by a batted ball with runners on second and third, and in a strikeout with the bases loaded.

23s, by the way, were given exclusively to pitchers, and every pitcher got one — but I’m getting ahead of myself. We’ll go into play result frequencies in a later post.

Another way to think about plate appearances is that these are results after which the original batter is no longer at bat. I guess you can think of these as times when you need to turn the page in the book. If there’s a “0” in that chart above, it means that the batter remains at bat — even if he won’t come back up until the next inning.

National Pastime At Bats

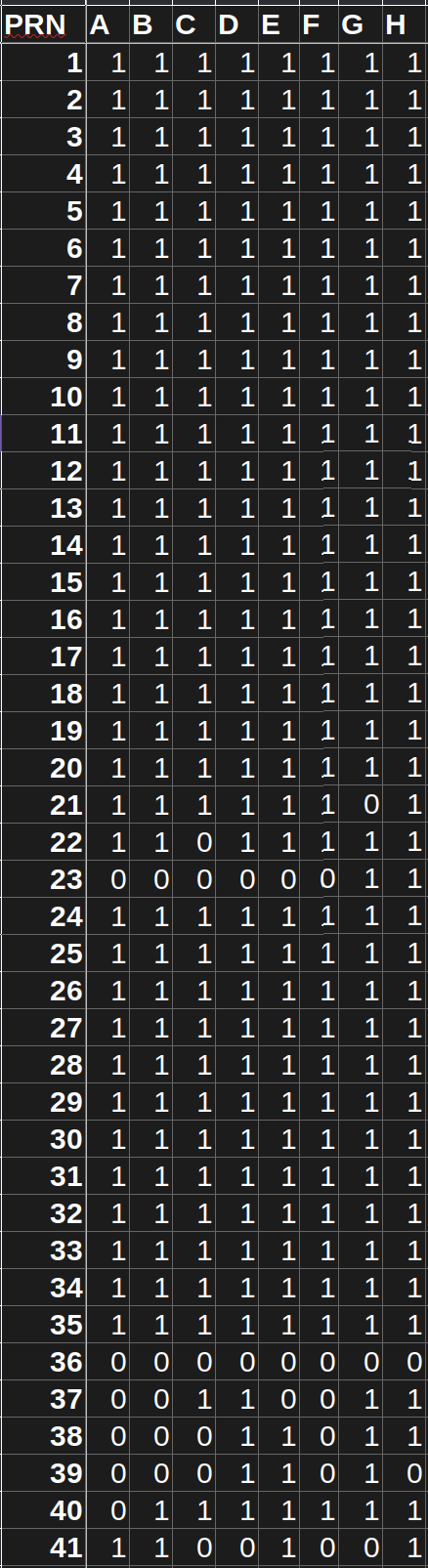

Now we’ll look at the at bats.

This is where the patterns become much more obvious. In fact, when we look at these patterns, we start to see general trends that will help us organize the boards as we move forward.

In general, play results on the National Pastime boards are broken up as follows:

1: Home run (1 is a home run regardless of the base runner situation)

2 through 6: Extra base hits

7 through 11: Singles

12: Special (we’ll talk about the 12 later)

13: Strikeout (13 is a strikeout regardless of the base runner situation)

14: Walk (14 is a walk regardless of the base runner situation)

15 through 21: Errors (with some exceptions)

22: Special (we’ll talk about 22 later)

23: Special pitcher number (again, we’ll talk about this one in more detail later)

24 through 29: Ground outs (sometimes resulting in double plays, sometimes not)

30 through 32: Fly outs (sometimes sacrifice flies, sometimes not)

33 through 34: Pop outs (these appear to be divided on the player cards according to player handedness; we’ll talk about this later)

35: Static outs (a 35 will never advance a runner or change the on base situation)

36 - 41: Unusual plays

It’s here in this at bats chart that you can see all of this in action. Play result 14 never results in an at bat, since it is always a walk. Results 15 through 21 never result in at bats: they’re either errors or result in the batter being hit by the pitch. Results 22 and 23 are special and rarely result in at bats. And results 36 through 41 are also special, sometimes resulting in at bats, but usually not.

More To Come

Now, we can’t just jump from this step to throwing out predictions as to how often the boards will yield each potential base situation.

The problem we have is that these play result numbers are not evenly distributed.

There are 36 possible dice results and 41 play result numbers. This obviously means that not every player will receive every one of these numbers. It also means that it’s going to take a while for us to figure out how frequently those base situations are expected to come up in National Pastime — and it’s also going to take a while to figure out what averages the cards should result in.

One thing is clear, however. Clifford Van Beek didn’t just create a game to emulate batting average numbers. There’s a lot more going on here than just that.