1929 or 1930?

If you know the history of National Pastime, you’re going to think this is a silly question.

Since the beginning, we’ve always “known” that the cards were based on the 1930 season.

That’s what The APBA Journal reported back in 1976:

Now, we know that at least one thing is inaccurate here: there were actually two white dice, not one white and one black die. One die was bigger than the other.

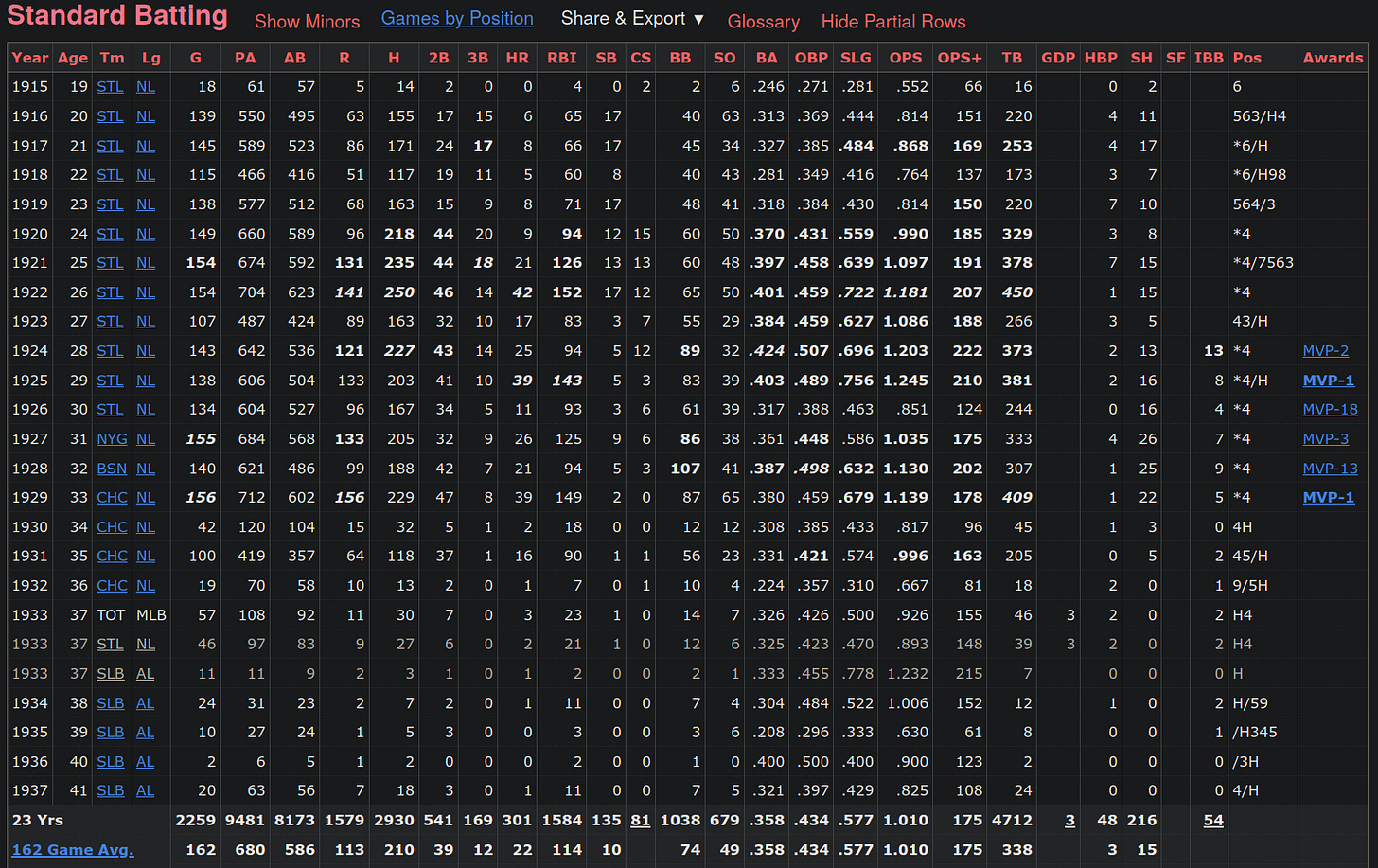

It’s also not surprising to see the conclusion that Van Beek used Rogers Hornsby’s 1929 season, since he was out for most of 1930:

That decision makes even more sense when you consider that Van Beek likely wanted to make cards based on the players’ actual abilities, not necessarily limiting them to only a single season. And Hornsby was a great star around the nation, after all. It would have been odd to leave him out.

What Was Van Beek’s Source?

The next paragraph of that old APBA Journal article, however, absolutely has to be incorrect:

The problem here is not that Van Beek was referred to as “Clayton West” in this article; Peter Simonelli gave him a pseudonym in an effort to try to quell Seitz’ anger about the piece.

No — the problem here is that there was no 1930 Sporting News baseball guide.

That should have been obvious to anybody involved. It’s actually obvious today, especially if you collect old baseball guides.

The Sporting News didn’t start publishing baseball guides until 1942. You can find numerous references to this online, such as here. There’s a great story behind those guides that came out between 1942 and 1946, which serves mostly as another commentary on how ridiculous Commissioner Landis was — but we’ll leave that for another time.

Van Beek might have been referring to the 1930 Sporting News Record Book, but I doubt it. A cursory glance at scans of the 1924 Sporting News Record Book will show you that there wasn’t anything inside that Van Beek could have used to create his cards.

The Timing Issue

Now, there were baseball guides printed in 1931. If Van Beek were to use a baseball guide as his source for the official 1930 statistics, he had two guides to choose from. He could have used either the Reach or Spalding guides.

But this is where we run into a bigger issue: timing.

This is the earliest advertisement for National Pastime that I am aware of:

This advertisement appeared on the back page of the issue of The Sporting News that came out on December 11, 1930. I’ve blown it up here; the original would have looked much smaller, unless you had a magnifying glass handy.

As far as I can tell, this is the only advertisement for National Pastime ever printed in The Sporting News. Please let me know if you find another.

Note here that Van Beek advertised his game as a Christmas gift. He couldn’t have done that were the cards not already calculated and printed by early December 1930.

Now, there’s a timing problem here — one so severe that the APBA community at large missed it for about two decades.

Back in the nascent days of the internet, before Facebook or YouTube were a thing, I used to spend a lot of time over at a website called APBA.zip. It’s still up today, actually. It was one of the gathering places for APBA players, and contained homebrewed data disks and all sorts of other useful utilities.

20 years ago, back in 2003, a copy of that same Sporting News page was uploaded to APBA.zip — in the Utilities section, for some strange reason. Here’s what the page looks like today:

Now, you can see the problem here, can’t you? The website identified this page as being published in 1931, not 1930.

And it makes sense, right? If Van Beek was going to use the official 1930 statistics, it would be extremely difficult for him to actually publish the game in 1930!

Sometimes we forget that baseball statistics were not as readily accessible in those days as they are today. Van Beek couldn’t just saunter off to his local library to consult the latest edition of The Baseball Encyclopedia, much less mosey on over to Baseball Reference and scrape all the data he needed.

What’s more, it turns out that both the 1931 Reach and Spalding guides were delayed.

The article above comes from April 20, which shows just how late the Reach guide was. The 1931 season had already begun.

The Spalding guide was out a little bit earlier, but also later than usual:

March 26 is still pretty late. You might recall from this post that the 1908 guides came out in mid-March.

I don’t have a copy of either the Spalding or Reach 1931 baseball guides. I haven’t been able to find any copies online. My understanding is that they were printed in smaller quantities than the guides from other years, largely due to the economic turmoil of the times. They do surface on eBay from time to time, but it’s much easier to find guides from the 1920s, 1910s, 1900s, and even the 19th century than anything from the early 1930s.

There is simply no way that Van Beek could have used either of the 1931 baseball guides to create his cards. The timing doesn’t add up at all.

The Sporting News

Is there a chance that Van Beek got his statistics from The Sporting News?

It’s possible, but really unlikely.

The Sporting News didn’t publish extensive statistics during the regular season in 1930. The closest thing Van Beek could have found in its pages during the regular season would have been a brief summary like this:

There’s simply not enough information here for National Pastime cards. It’s also extremely frustrating to see the batting statistics for relief pitcher Al Shealy at the top: Shealy had a grand total of 5 plate appearances for the Cubs in 1930.

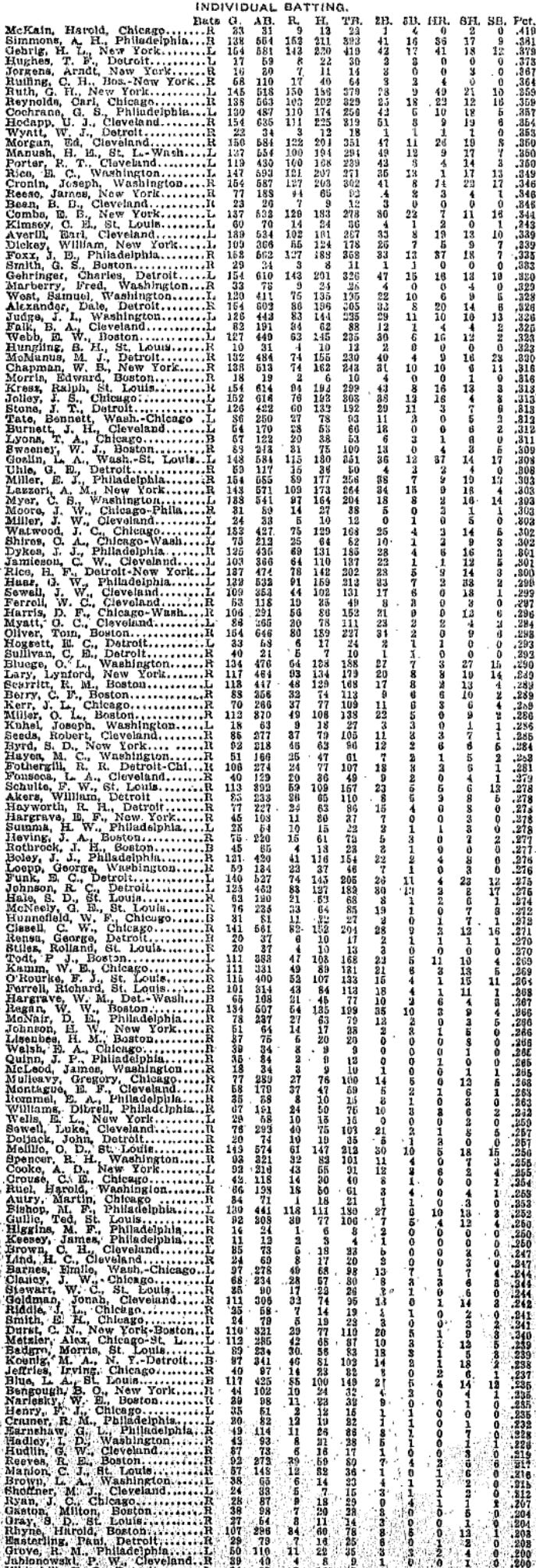

Now, there were statistical reports in The Sporting News after the end of the season. This is more like what I expect Van Beek would have used:

As you can see, this list has doubles, triples, home runs, stolen bases, and even caught stealing numbers. In fact, a separate listing on the same page has strikeouts, walks, and hit by pitch totals for selected players:

However, there are a few problems here that might not be fully obvious.

First, the players and their positions are completely disconnected. In fact, the defensive statistics didn’t come out until the December 11, 1930 issue of The Sporting News — which happens to be the same issue that contained Van Beek’s advertisement:

Now, remember that Van Beek labeled his players only as “outfielder,” “infielder,” “catcher,” and “pitcher.” Fielding clearly was an afterthought. However, the statistical issue of The Sporting News doesn’t even contain that basic information.

The other problem, of course, is that the National League stats are missing.

Those 1930 National League stats weren’t published by The Sporting News until January 1, 1931:

You see, the problem we keep running into here is that Van Beek’s advertisement came out in The Sporting News on December 11, 1930. It’s clear that he was trying to get the game out before the 1930 Christmas season. Based on the wording in the advertisement (“Shipment will be made the day order is received”), I’ve got to conclude that he had the game boards and cards ready to sell right away.

Daily Newspapers

There’s always the chance that Van Beek got his stats from a daily newspaper instead.

While possible, it’s not really plausible.

Now, I’ve got to admit that I don’t have access to any Milwaukee newspapers from that period. This is due to the monopoly that Proquest maintains on certain newspapers. That’s a rant for a different day.

I do have access to The Chicago Tribune, however, which was a major newspaper in a city with two major league clubs. I’d assume that The Chicago Tribune would be more likely to print complete statistics than newspapers in cities that did not have major league teams.

After a bit of searching, I was able to find unofficial American League statistics at the end of the season:

Of course, these statistics did not include doubles, triples, walks, or strikeouts.

The National League stats appeared in the same issue, though without those extra numbers. I also suspect that there weren’t enough players per team to create National Pastime:

There’s also always the chance that Van Beek compiled his own statistics based on boxscores, in sort of a proto-Bill James sense. I strongly doubt that would have happened, though. There was no need for it, after all. All the statistics Van Beek needed came out in the official baseball guides; there’s no reason for him to compile them himself.

The 1930 Spalding Guide

Though there aren’t any scanned copies of either 1931 baseball guide available online, there are scans of the 1930 Spalding guide.

This is what the statistics looked like:

Again, these are the statistical categories that Van Beek likely used. Remember, though, that these statistics were based on the 1929 season, not 1930.

There were also records of walks and strikeouts per batter:

It seems, though, that these miscellaneous statistics were only reported for starting players.

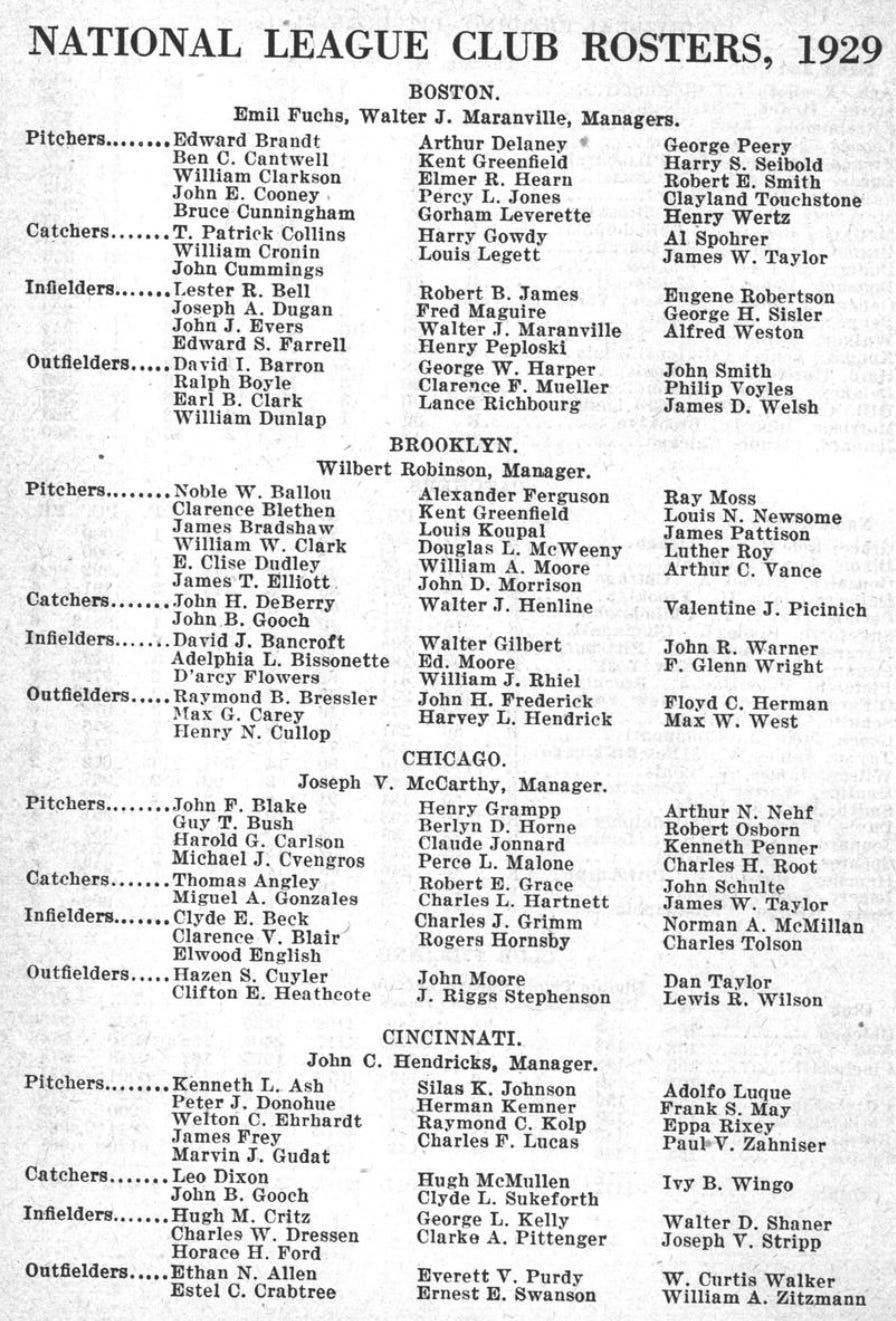

And, finally, there were roster listings like this:

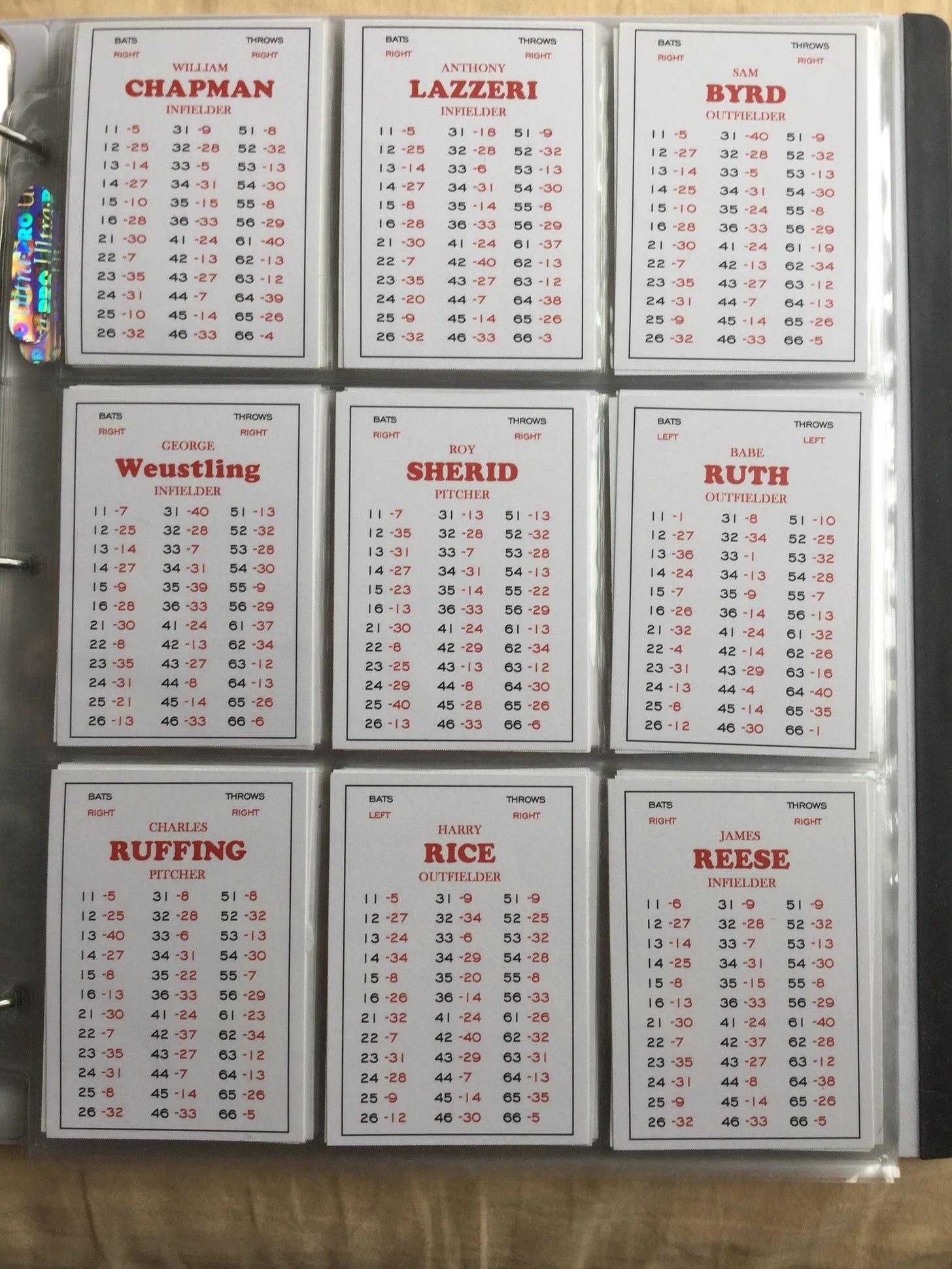

I think that this is almost certainly what Van Beek used. As a result, I very strongly suspect that National Pastime was actually based on the 1929 statistics, not the 1930 statistics.

Now, it’s odd that Van Beek would have elected not to use the fielding and pitching statistics that were in the same guide. We’ll explore that subject in more depth later.

Another Clue

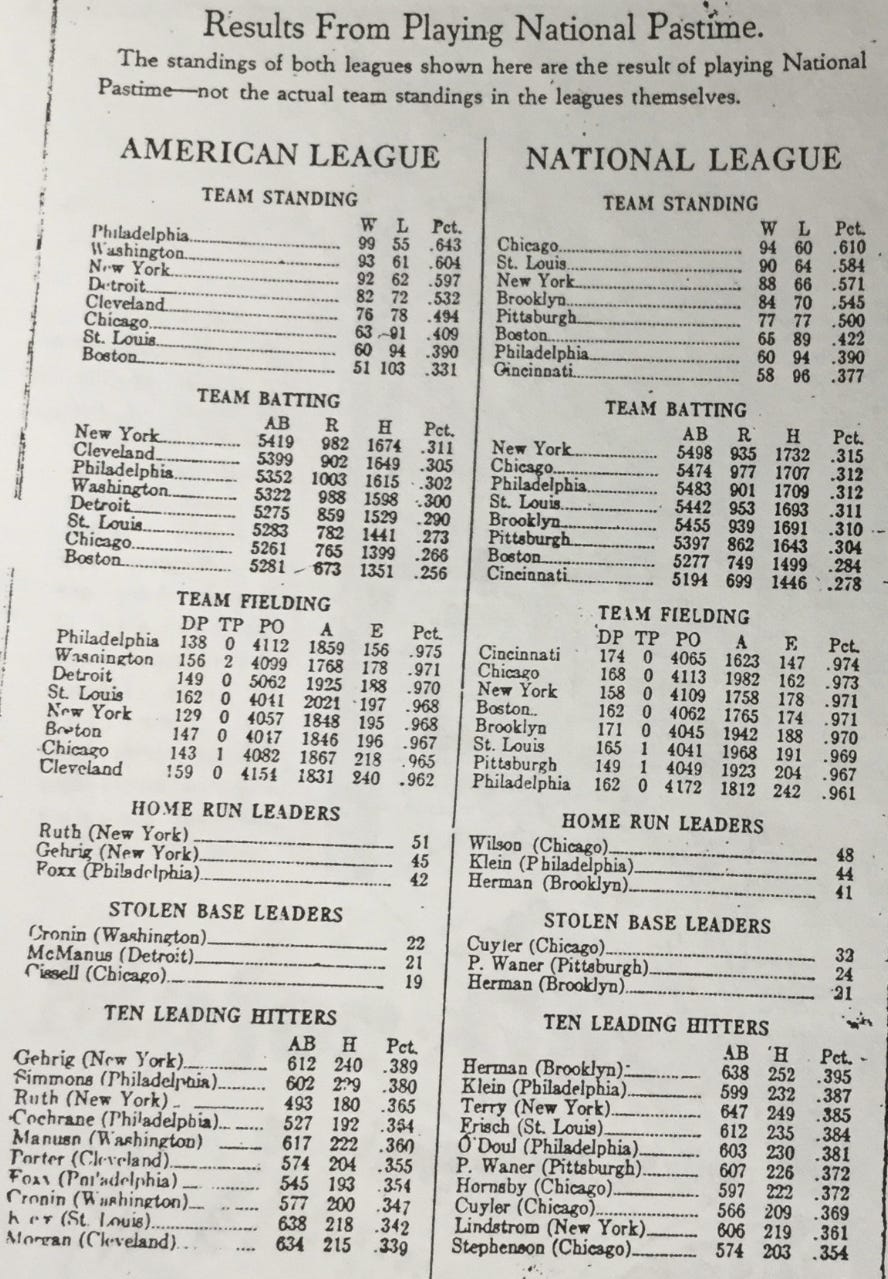

While looking through my photos of the papers that were included with the old National Pastime reprint game, I came across this:

I don’t know where this originally came from, though I’m guessing that it was part of Van Beek’s original brochure. My guess is that this came from the J. Richard Seitz estate.

For the sake of comparison, here are the 1929 final standings from Retrosheet:

And here are the 1930 final standings:

I’ll let you be the judge.

Now, I presume that Van Beek played this season replay himself, assuming that the origin of this is Van Beek’s original brochure. I think it’s possible that he tried to follow real-life 1930 transactions, playing along with the season the way that kids used to play Strat-O-Matic seasons.

Furthermore, we know that J. Richard Seitz and his friends played a complete draft league for the 1931 season, which I presume started sometime in April 1931. Again, it would have been very difficult for Seitz and his teenage pals to complete a full season if they didn’t already have the cards. We’ll go a bit deeper into that fact in the future.

Mystery Solved?

As I look into the origins of National Pastime, there are a few things that I’m becoming convinced of:

Clifford Van Beek offered National Pastime for sale in December 1930, planning on capturing Christmas season traffic.

Van Beek spent time calculating cards for his game throughout 1930, using one of the 1930 Baseball Guides and basing his ratings on the 1929 statistics (I’m guessing it was the Spalding guide, since the roster listings correspond so closely to National Pastime’s position listing).

Van Beek overestimated the demand for his game in late 1930, and found himself heavy on games and low on customers.

J. Richard Seitz likely received the game as a Christmas present in 1930 (I’ll admit this is extremely speculative, but there is a method to my madness: more on this later).

Van Beek’s game was a commercial failure, causing his Major Sports Company to go bankrupt in early 1932 after losing a lawsuit to his printer.

The surprising bankruptcy of Van Beek’s company inspired Seitz to fiddle around with ratings and card creation himself over the years, paving the way for what would eventually become APBA (and explaining a lot of Seitz’ miserly policies in the early years).

Now, a lot of this is speculative. I’m more than happy to change my opinion on this subject. I’d love to hear from the rest of you!