Why The Wait?

This one is going to be very speculative, so be warned.

Clifford Van Beek’s National Pastime patent application was granted in 1925 — on May 5, 1925, to be exact. However, his game was not released until late 1930. Why did it take so long?

The Game Wasn’t Finished Yet

We know that Clifford Van Beek had an early draft of National Pastime ready by September 17, 1923, at the very latest.

How do we know that? Simple: that’s the date the patent application was filed.

The full patent application was filed on September 17, 1923, at least 7 full years before the game was finally released.

Now, it would be incorrect for us to say that this early draft was exactly the same as the final version. In fact, we can do some quick comparisons to see.

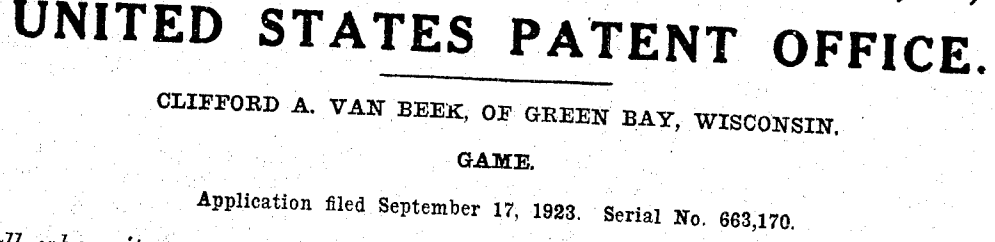

Take a quick look at None On Base, for example:

And here are the same 12 results in the final game:

Leaving aside the hit location text, results 1 through 10 are quite similar. Van Beek did change 11 into a single with a stolen base, and play result 12 moved away from being a single at some point.

There are two more boards that we can compare briefly. First, there’s the Runner on Second board:

And here is what the final results 1 through 10 tool like on the final boards:

You can see here that many of the aspects that make the National Pastime boards so unique and fascinating weren’t quite ready in 1923. Play result 3 became a home run with a runner on second, 4 became a triple, and, most famously, 5 became a home run.

I suppose that it is also possible that result 10 originally included the runner being thrown out at home by the left fielder. It seems that this part was inserted for the sake of pointing out that the boards would have outs written in. From the patent text:

It would be interesting if the hit results that included outs were a different color than the other results.

Finally, let’s look at the Bases Full boards:

And here is the final version:

The only difference that is clearly visible here is play result number 6, which changed from a bases-clearing double to a triple. As we’ll see in a future post, these power number changes were likely made in order to give Van Beek the ability to fine tune double, triple, and home run results to a certain extent.

In short, it’s pretty clear from the version of the boards in the patent that they were not yet in their final form.

By the way, the cards more or less took their familiar form in those early days:

APBA players will probably look aghast at the sight of a 12-36, 31-36, or a 52-22 reading. However, the basic form of the cards is very similar to what they would wind up being in the end:

We can argue, though, that the game simply wasn’t ready in 1925. I think it would be hard for us to explain why it still took 5 years to make the changes that Van Beek made, but it is a plausible argument.

No Money

This is where the speculation really comes in.

It costs money to print a baseball game. And there’s a good chance that Clifford Van Beek simply didn’t have that kind of money in the mid-1920s.

Now, we’re never going to know exactly how much money Van Beek spent on advertising. We do have some idea of how much he spent on printing, however. Remember that lawsuit article?

Van Beek spent $450 up front to get 500 games printed. According to in2013dollars.com, $450 in 1930 is the equivalent of over $8,000 today:

It’s not hard to imagine that Van Beek would need to save up extra money to pay for the initial printing.

Impact

Now, the sad part is that waiting had a negative impact on the salability of National Pastime.

I probably don’t need to go into much detail here. By waiting to bring his game to market until the Great Depression was fully underway, Van Beek missed out on a lot of the big money and fast times of the 1920s.

I think there’s a good chance that National Pastime would have had more commercial success had it come out in 1927 or 1928. Now, it is possible that Van Beek would have lost his shirt in 1929, just like so many others did. However, the game might have been better known had it not come out at a time when most people were struggling to make ends meet.