Before National Pastime

There are a number of old baseball games that have surfaced over the years. People have claimed that this one or that one might be the predecessor of National Pastime.

I think they’re all full of bunk.

However, there is one particular game that I was recently made aware of that caught my attention.

The Patent

Remember all the noise I made about the National Pastime patent?

Well, there’s a game that was granted a patent in 1914 that looks an awful lot like National Pastime — minus the individual cards, that is.

This game was created by a man named Charles M. Steele, and it’s absent in those old APBA Journal articles.

Take a look at the patent for yourself:

Look at what we have here:

Playing boards with different charts for each base situation

A playing board that folds inward (the same as the National Pastime system)

Three identical dice that are rolled together and combined (not added)

Now, Steele applied for this patent on October 17, 1913, as noted above. Remember this date: this becomes somewhat important later on.

The Game

When we look at the game itself, the similarities become even more obvious.

Steele’s game was originally called “Steele’s Inside Baseball.” It looked like this:

Per the auction listing, this board was apparently manufactured in 1911. Actually, I strongly doubt that date, and will note that there is no visible copyright date anywhere — including on the outside boards when the game is folded up:

That playing board looks an awful lot like the National Pastime boards. Here they are for comparison:

National Pastime offered the same basic folding board design, as well as the same layout of on-base situations combined with a playing field. It seems obvious to me that National Pastime’s general layout and structure was based on Steele’s game.

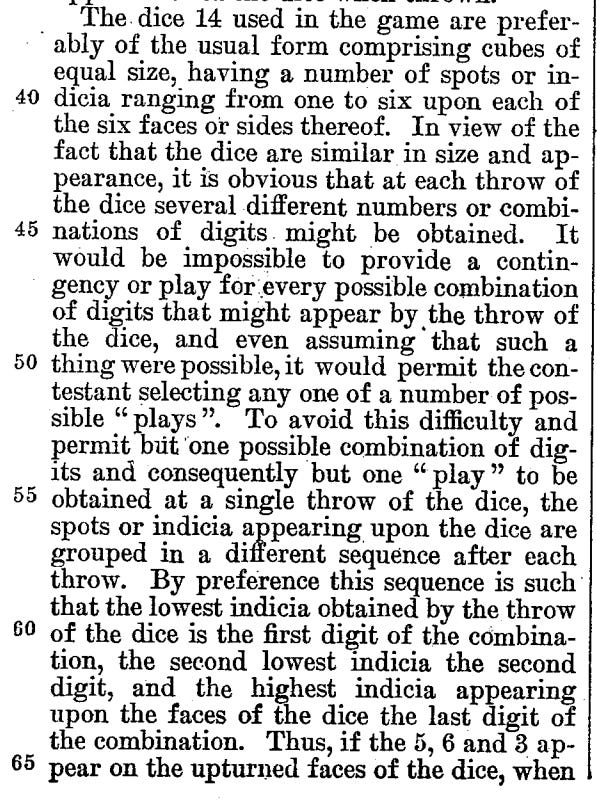

The Dice

Now, Steele’s game used three dice instead of two, as I mentioned above.

The way these dice were combined is a bit esoteric. Yes, they were combined together — but they were combined in a way that allowed for only 56 possible combinations, as opposed to 216.

Here is Steele’s description of this mechanism:

Don’t worry if you didn’t get that. It’s easy.

You roll three white dice of equal size. You then read them in sequence, starting from the lowest number and moving up to the highest number.

This gives you a total of 56 different combinations. Think of it this way: two “1” results give you 6 additional options; a “1” and a “2” give you 5 additional options (because a “1” from the third dice was already covered in the two “1”s section”), a “1” and a “3” give you 4 additional options, and so forth. It all adds up to 56.

Now, you don’t need to be a dyed-in-the-wool game designer to see that this isn’t a particularly efficient system. It’s complicated and confusing, and you don’t get much bang for your buck. National Pastime had 36 different dice combinations; this game gives you only 56 combinations, not the 216 that it could have had were the dice of different colors or sizes.

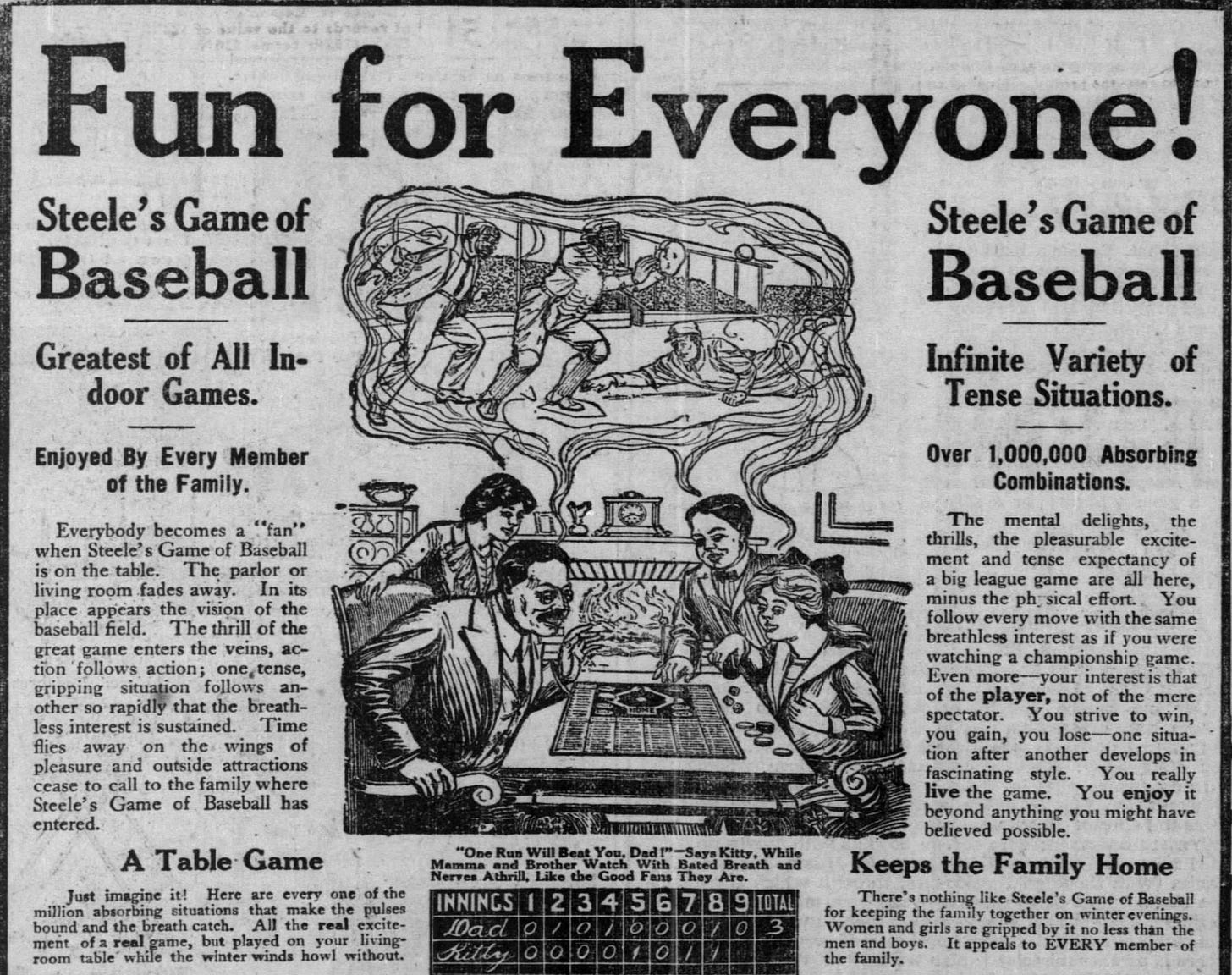

The Ad Campaign

This is where this becomes fun.

Advertisements for Steele’s Inside Baseball are actually really easy to find. And they almost all come from 1913.

This is the earliest I could find:

Note that this ad appeared in a newspaper in Decatur, Illinois on October 28, 1913.

There were other similar ads in Illinois newspapers. Gradually, ads started to show up in other parts of the country, like this one from Kenosha, Wisconsin:

It’s listed here for $1.25 in the bottom half of this ad from the Stewart Dry Goods Company in Louisville, Kentucky:

Steele was apparently much more successful at penetrating the retail market than Clifford Van Beek would be, not to mention J. Richard Seitz.

However, I’m not convinced that Steele’s game was necessarily a best seller. My skepticism comes because Steele apparently changed the name of the game sometime in 1914.

It took me a little while to figure this out, but, well, here you go:

Steele apparently was also looking for salesman for his game — perhaps to go door to door?

It seems that Steele was looking for boys to sell his game to other boys. This comes from an issue of St. Nicholas Advertisements from what I think is November 1914, based on other pages:

By the way, the 448 number is simply 56 times 8.

Actually, if you waited, you could get a copy of the game down in Fort Worth, Texas, for 50 cents, according to this Burton Dry Goods Company ad:

Now, Steele was apparently quite a self promoter. Check out this advertisement in The American Stationer from late March 1915:

I don’t believe the game actually sold “approximately 100,000 copies” — certainly not if department stores in Texas were selling it for pennies on the dollar. Steele’s policy of having his customers find their own customers doesn’t make me feel confident that his game was simply selling itself.

Anyway, Steele’s game remained on sale through the 1915 World Series:

This advertisement from Houston in 1916 is the last ad for Steele’s game I could locate:

But one of Steele’s advertisements tops all of these put together.

That would be this one, in the December 19, 1915 issue of The Chicago Tribune:

Let’s take a closer look at this. Here’s the top half:

I mean, this isn’t necessarily the greatest prose in the world, though it certainly is different than the standard “You Are The Manager!” fare many of us have grown accustomed to.

Meanwhile, the bottom half has received attention from a number of blogs:

I’m not sure I’ve seen any other advertisements from 1914 or 1915 that featured players from all three Chicago teams.

A Question of Timing

There’s one question we need to address here. Was this game produced before 1913?

Honestly, I don’t know. Most websites list it as having copyright dates going back as far as 1911. Here’s an example:

Even though the earlier Heritage auction is probably proof that I’m wrong, I still believe that Steele didn’t sell his game until 1913. The reason is because he didn’t create his company until October 1913.

Check this out:

If you look back up, you’ll notice that Steele’s patent application was filed on October 17, 1913, and that the first advertisement for his game came out on October 28, 1913.

I could be persuaded to believe that he started selling the game before all this — but I would need to see some kind of evidence. Everything I’ve seen comes after October 4, 1913, the date of this affidavit.

Influence on Van Beek

So what does all of this mean?

I think that Van Beek was likely influenced by the layout of Steele’s game. But that’s it.

It would be incorrect to say that Van Beek lifted anything else from Steele’s game. Look at the significant differences:

3 dice instead of 2

Lack of individual player cards

Excessive number of “strike” and “ball” results (you can see this in the patent figures and in the pictures of the boards, too, if you zoom in)

Lack of correspondence between dice rolls (i.e. a 112 with nobody on base is a single, but is a force out at second with a runner on first)

However, we do have proof that Van Beek was influenced by Steele’s game.

Look closely at the wording from Steele’s patent:

That’s right — “None on bases”. Not “Bases empty” or “None on base.” Go back up and look at the picture of the published game, and you’ll see it there as well.

“None on bases” might be grammatically correct, but I’ve never heard or read that phrase in a baseball context.

Except in one other place.

That phrase, “None on bases,” is so odd and strange that it stuck in my mind after I studied Van Beek’s patent. As soon as I saw it in the Steele patent, I grasped the connection.

I’m convinced that the young Clifford Van Beek played Steele’s game, and decided to use its basic structure for his own. At some point during the production process, Van Beek changed to the more idiomatic “None on base,” which is the wording used in the official National Pastime game. It was J. Richard Seitz who modified that to the more conventional “Bases Empty.”

The Final Word

So what does all of this mean?

It’s clear that Van Beek was influenced by Steele’s game. Actually, I’d argue that Fan-I-Tis itself is also largely based on Steele’s game. From what I’ve seen, it seems that Steele had the more active advertising campaign, and probably moved more units.

I don’t think either Fan-I-Tis or Steele’s game were influenced by Pocket Base Ball or Fan Craze or whatever. It’s not particularly remarkable that different people in different places came up with baseball games based on dice rolls. I mean, if you trust this site, variations of “dice baseball” have been passed down from generation to generation. It’s not really that special or interesting.

Note, by the way, that Steele’s game uses dice precisely the same way that those old dice baseball games used them: roll 3 dice of identical color, combining the number starting with the lowest roll.

Van Beek made a few major modifications that made his game stand out from the rest:

He used a matrix system to connect dice rolls with play results, effectively expanding the possibilities from 36 dice rolls

He created individualized player cards

He balanced the play results to prevent certain board situations from occurring too frequently or too infrequently

He combined those play results with a ingeniously arranged power number system to give himself a finer touch in recreating extra base hits

This is why I consider the quest for Van Beek’s influences to be largely in vain. Instead of focusing on where he got his ideas from, we should spend more time analyzing what he actually did.

And that’s what we’re going to look at in the future.