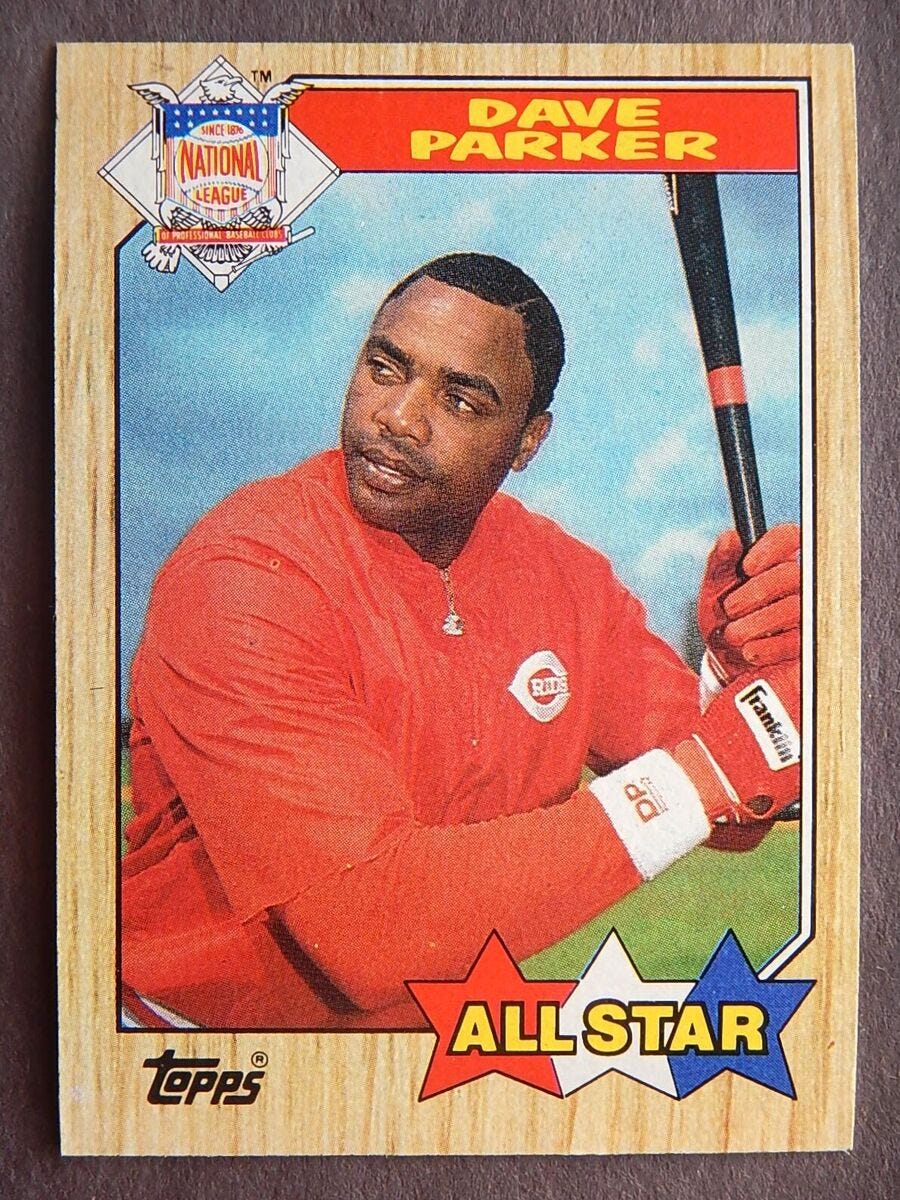

Dave Parker's Defense

I came across this snippet from the 1978 Bill James Baseball Abstract the other day:

James is correct about refraining from trying to steal bases when you keep getting caught, of course. But the more fascinating part here is Dave Parker’s defensive statistics.

Parker’s defensive statistics are actually quite controversial. As you may already know, Parker’s poor defensive statistics in 1986 have been the subject of controversy for several years now, as evidenced in this short article by Sean Smith, the man behind the fielding aspect of WAR:

Now, this discussion is a bit deceptive. The question seems to be about whether WAR underrates RBIs. Parker had 116 RBIs in 1986 — an offensive performance that led him to finish 5th in MVP voting and to be elected to another all star game.

But WAR doesn’t discount players for driving in a lot of runs. Instead, WAR discounts players for playing poor defense. And apparently Dave Parker was awful defensively in 1986.

So what happened? How did he go from leading the National League in both assists and putouts in 1977 — while playing right field — to being such a defensive liability that he wound up Oakland’s designated hitter in 1988?

Now, there’s a lot missing here, and I blame both Bill James and Sean Smith for not doing their research. As I explained in this article, Parker almost didn’t play at all in 1986 due to his well known drug issues:

Now, if you ignore rfield and its secret formula for a second, you might be convinced that Parker’s defense never really declined. Here are his raw defensive numbers from 1973 through 1986, thanks to Baseball Reference:

Can you spot the decline? Parker’s fielding percentage was consistent over the years. His assists decreased from that high of 26 in 1977 — but that’s clearly because players stopped running on him. He no longer was netting over 400 putouts in a season, though that only happened in 1977. 296 putouts in 1986 was a bit of a letdown from 348 in 1985 — but, then again, he was playing in right field.

It’s that Rtot/yr section — which is basically what Baseball Reference uses as rfield — that discounts him.

Now, it’s impossible for me to say definitively what caused this shift. We can’t say much without knowing how in the world rfield is calculated, which, apparently, is a state secret. However, I’d argue that there are a few things that we could guess at.

It’s not likely that Parker’s defensive abilities declined so rapidly. Going from that high of 21 fielding runs in 1977 to a low of -18 fielding runs in 1981 makes very little sense to me. How do you go from being the best outfield in baseball at age 26 to one of the worst at age 30?

Omar Moreno played in center field for the Pirates in 1977, and wound up with 14 fielding runs. It’s not that Parker was stealing balls away from Moreno. Is it possible that Pirate pitching was giving up an unusual number of fly balls that year?

Parker’s throwing arm clearly did not deteriorate all that much by 1986; he still had 10 assists and was part of 2 double plays, which is pretty good for a right fielder.

Remember that Parker’s decline in assists after 1977 was probably because word got out in the National League that you shouldn’t run on the Cobra.

In 1986, Parker was playing next to Eddie Milner, the center fielder for the Cincinnati Reds. Milner also had a negative fielding season, though he hit a platry -2. Is it possible that Reds hurlers gave up fewer fly balls than expected, and that this hurt their outfielders?

Now, I’ve said this before, and I’ll say it again and again. It’s silly to discount a good offensive season by a corner outfielder because his defense was theoretically not up to par. If the player truly was on the field for his defense, he wouldn’t be playing in right field.

I like how WAR handles hitting, and don’t have many qualms with how it handles pitching. However, the way WAR handles fielding for seasons before FieldFX and other modern statistics is simply awful. It’s nothing but guesswork, and it’s very likely that the noise is getting in the way of the signal.