National Pastime Pitcher Cards

When we looked at pitcher cards in our last post, I noticed that there was something odd. At just a glance, it seemed that pitchers in National Pastime tend to have more 13 play results and fewer 14 results than other players.

It’s not really hard to see this when you map it out. There are a total of 80 pitchers in National Pastime, 5 per team.

I started to wonder if there might be a pattern that dictated where the “extra” 13s were placed on pitcher cards. Of those 80 pitchers, no fewer than 32 have 7 “13” results on their cards, and an additional 16 have 6 “13” results. George Uhle has only 2 “13” results, the only pitcher who does not have 3 or more. In fact, only 3 pitchers have a mere 3 “13”s, and only 4 wound up with 4.

All cards in National Pastime have at least 1 “14.” However, only 2 pitchers have 2: George Uhle (who only has 2 13s) and Charles Lucas (who only has 3 13s).

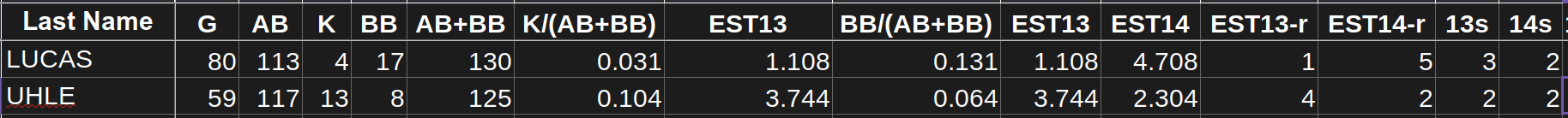

There’s really not much of a pattern here, by the way:

Even if you grant that my formula is inelegant, it’s hard to figure out what Clifford Van Beek based either decision on. We’d estimate that Lucas should have received only a single 13, since he struck out only 4 times in 113 at bats (or 130 estimated plate appearances, if you account for his walks). We’d also estimate that he would need about 5 14s for those 17 walks, instead of the mere 2 that he received.

Uhle looks a little bit better. We’d estimate that he would need 4 13s to recreate the 13 strikeouts he had in 117 at bats (125 if you count in the walks). He’d also need around 2 14s for his 8 walks, which is exactly what he received.

As I’ve said before, this is where things are puzzling. There isn’t a clear pattern to indicate that we’re off by a number going one way or the other. In fact, when you look at pitchers in aggregate, it seems more likely that 13s and 14s were largely assigned without paying any attention at all to actual strikeout and walk numbers.

But now we’ve got to ask ourselves how in the world those numbers were assigned.

Pitchers Are Easier

Now, there’s a reason why we’re working with pitchers first. They’re easier.

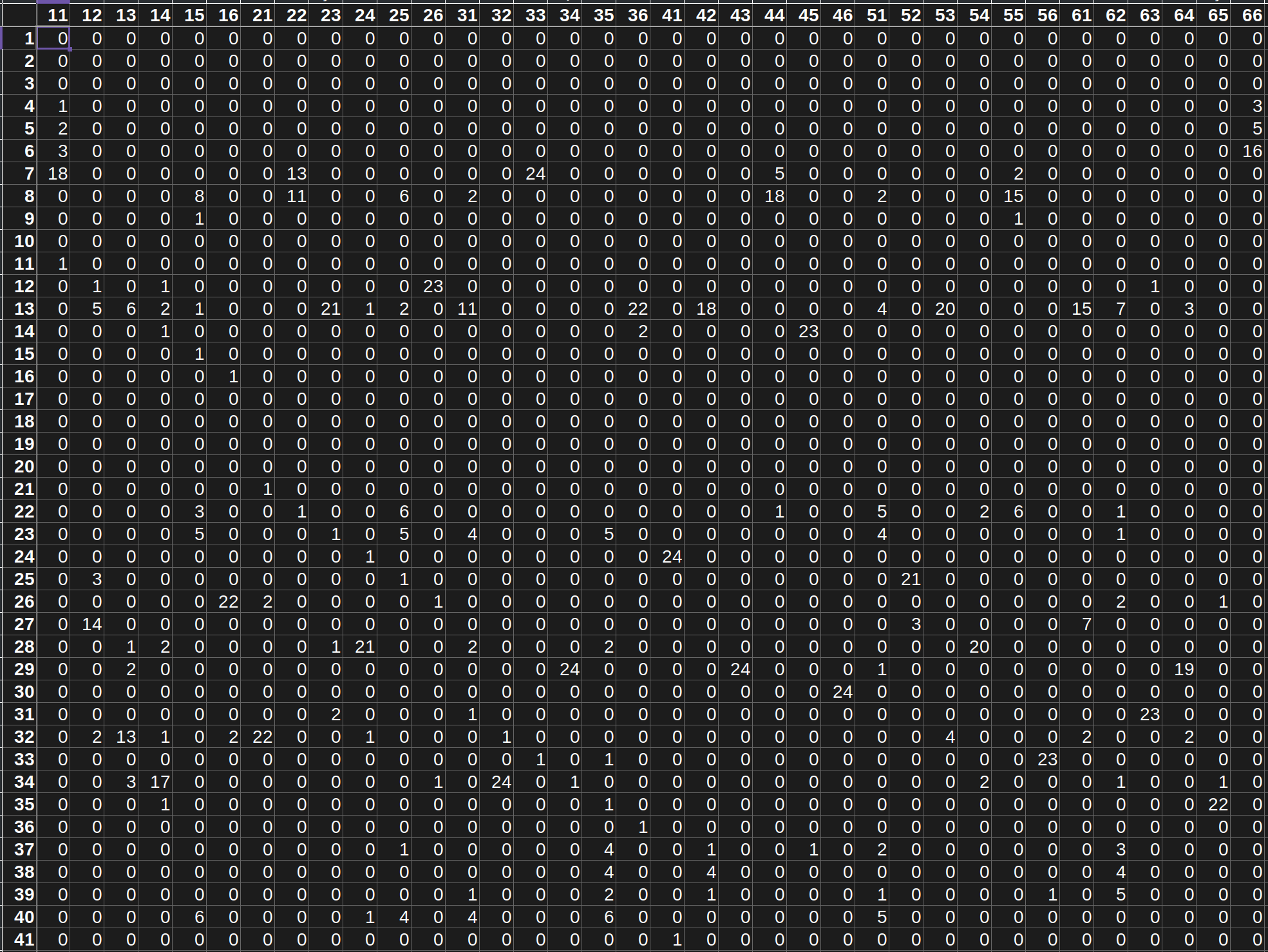

This chart shows how frequently each play result number shows up on pitcher cards:

Pitchers in National Pastime never receive the following play results:

1

2

3

10

11

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

36

41

That 14 different play result numbers that simply don’t come up on pitcher cards. Almost 35% of possible play result numbers simply don’t show up on pitcher cards.

Though it might be a bit confusing, this chart also tells us a few things important to our discussion:

Over 50% of all 13s assigned in National Pastime wind up on pitcher’s cards (significant, since pitchers make up 28% of carded players).

100% of all assigned 23s are on pitchers cards.

As we saw before, every pitcher also has exactly one 22. Only 20 other players received a 22.

Every pitcher has exactly one 24 and one 25.

Only 2 pitchers received a 9, which should be surprising to APBA fans. Pitchers account for less than half a percentage of all 9s in National Pastime.

I could go on. With that said, let’s see if we can find “sample cards” for National Pastime pitchers.

Right Handed Hitting Pitcher Sample Card

Now, we know from our prior research that Clifford Van Beek likely used “sample cards” for right handed and left handed batters. We’re going to take the same approach here.

We’ll start with right handed hitting pitchers first.

First, here are the dice roll frequencies for every right handed hitting pitcher in National Pastime:

If we look only at play result numbers with double digit frequencies, and if we ignore dice roll numbers with multiple candidates (like 42), we get the following sample card:

It feels like we’re starting to get somewhere now. A few things to note:

This sample card has 6 “13”s. As we learned above, most pitchers in National Pastime have 6 or 7 “13”s. Interestingly, most pitchers have the “extra” 13s on the same dice rolls.

This sample card only has 1 “14,” which, again, tends to be on the same dice roll.

Almost all pitchers have a 7 on dice roll 11.

Almost all pitchers have a 6 on dice roll 66. I haven’t checked yet, but it seems that this is true regardless of whether the pitcher had an extra base hit in real life.

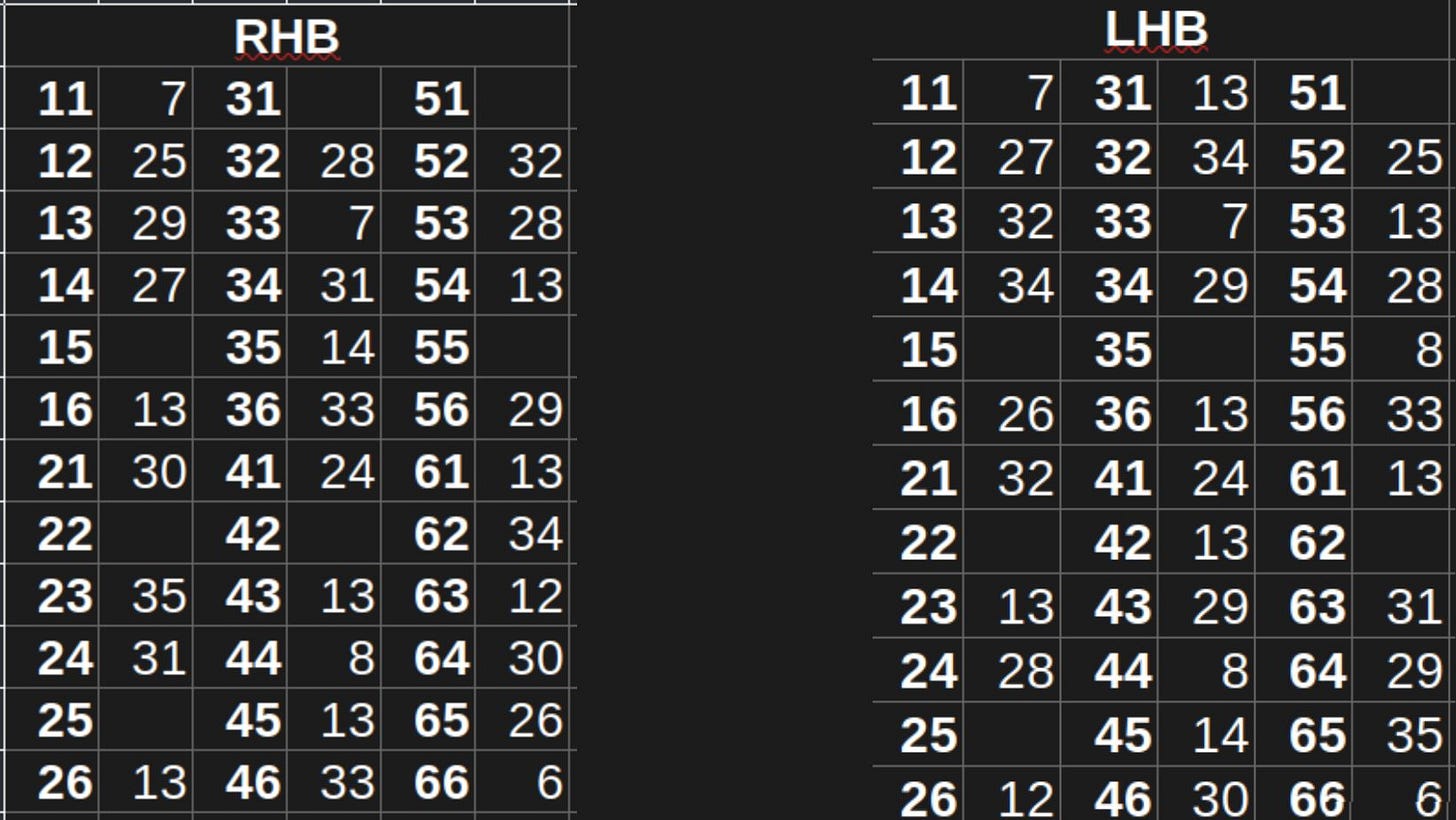

To see the contrast more clearly, we can compare this with the generic right handed batter sample card we came up with earlier. The generic one is on the left; the pitcher card is on the right:

We’ll focus on the 13s and 14s for now, since that’s what got us into this mess. We can see the following trends:

The 14 on dice roll 13 has been replaced for pitchers — usually with an out number (when not 29, it tends to be a 25, 27, 28, 30, 31, and so on).

Dice roll 16, normally a 28, turns into PRN 13.

Dice roll 26, normally a 32, turns into PRN 13.

The 14 tends to show up on 35, with very few exceptions.

PRN 13 on 42 moves over to dice roll 43; this is what we discovered last time with Adolfo Luque.

The 14 on 45 has changed to a 13.

Dice roll 54 tends to produce yet another 13, as opposed to a 30.

Dice roll 61 gives us yet another 13.

In short: the 14 moves to dice roll 35, and 13s pop up like wildflowers: on 16, 26, 43, 45, 54, and 61.

Now let’s look at the lefties.

Left Handed Hitting Pitcher Sample Card

First off, here are the raw frequencies:

Because the numbers are so small, I’ve combined left handed batters with switch hitters. We have good reason to suspect that this is what Clifford Van Beek did: see here for more.

Here’s the sample card we get:

Again, the best way to look at this is to compare it with our generic left handed hitter sample card. The generic is on the left and the pitcher card is on the right:

We’ll focus on the 13s and 14s for now:

Dice roll 23 changes from 31 to 13.

Dice roll 31, normally a “hit number,” is now usually a 13.

Dice roll 36 changes from a 14 to a 13.

Dice roll 53 changes from a 32 to a 13.

Dice roll 61 changes from a 32 to a 13.

Dice roll 64 changes from a 13 to a 29, which is surprising.

Overall, the sample pitcher card has 6 “13” play result numbers and only 1 “14” play result number, just like we saw with right handed hitting pitchers above.

So What?

This somewhat tedious exercise tells us a few things:

Clifford Van Beek seems to have relied on sample cards for most of the out numbers, with few exceptions.

Van Beek seems to have had different sample cards for pitchers than for other hitters.

Most pitchers were assigned a single 14 and 6 13s, regardless of how often they walked and struck out in real life.

The more I look at this, the more I have to conclude that National Pastime was likely designed to recreate batting averages more than anything else.

The other big question, of course, is why in the world all pitchers have a “double number” on dice roll 66 — usually a 6 (but sometimes a 4 or 5). We’ll talk about that next time.