Not All Extra Base Hits Are Created Equal

I wrote a few days ago about the odd phenomenon of power numbers in National Pastime:

Interestingly enough, it turns out that a double isn’t always a double, and a triple isn’t always a triple in that game.

Having looked deeply into the structure of Clifford Van Beek’s National Pastime game, I really have to conclude that Van Beek was more focused on creating a playable game that had some surprises than on making a simulation that was strictly true to life.

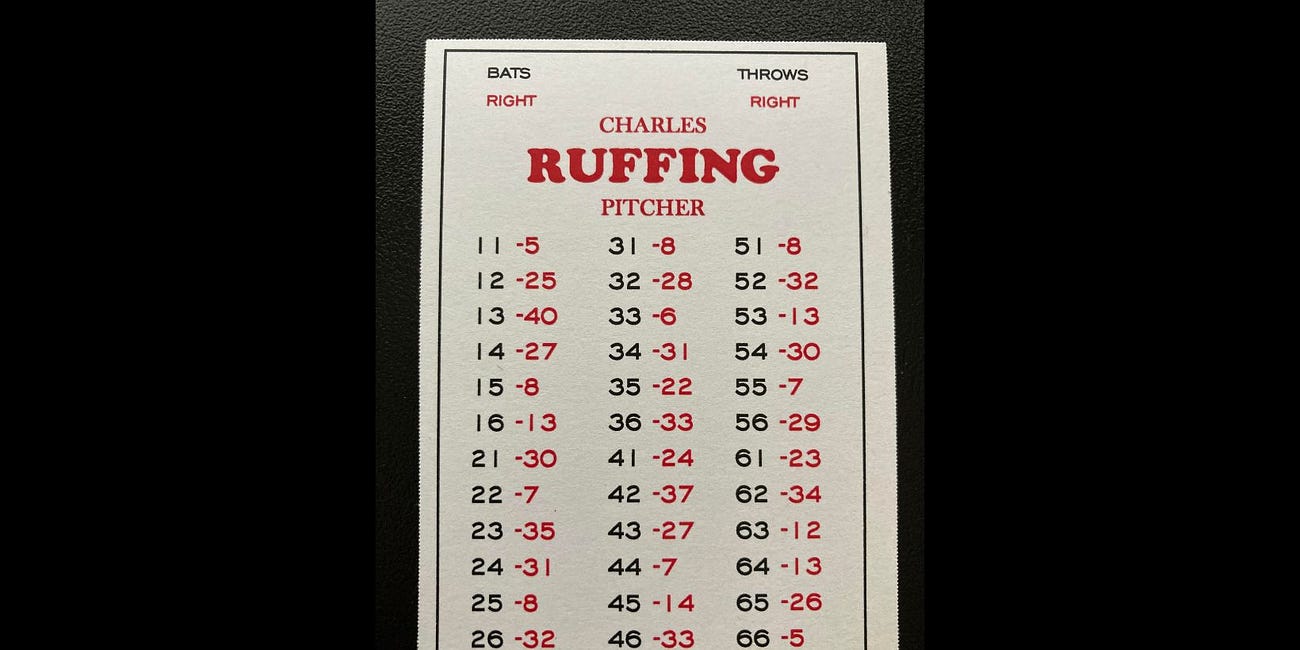

You’ll remember this chart from my last post, for example, which shows how inconsistent Van Beek’s “power number” results are from one base situation to another:

We could theoretically claim that Clifford was trying to fine tune the power numbers on his cards. This would require us to consider the frequency of various historical on base situations, something that I wrote about here:

Unfortunately, I find this subject to be pretty snooze inducing. It tends to be boring for a few reasons:

The on base situation data is extremely consistent over the course of baseball history.

The difference between one on base situation and another is miniscule — with the obvious exception of bases empty and having a runner on first.

This really only matters if we create a game with charts that differ with different on base situations.

There’s really no evidence that Van Beek used this information, or that he even cared about it.

It’s kind of silly to speculate about whether Clifford Van Beek had access to this particular data set or not. We know that he didn’t; in fact, nobody has had access to this kind of data until very recently, as far as I’m aware. Not only that, but we also know that Clifford Van Beek didn’t take any of these situation percentages into account when he created his player cards. We know this because every single batter in National pastime has at least one play result 6 on his card. That includes pitchers who never hit extra base hits, as I’ve explained here:

And here:

Now, what we can look at is what the National Pastime boards actually tell us. In other words, we can look at what base situation every one of those power numbers results in.

Some of this chart is pretty self-explanatory. Home runs will always leave the bases empty, for example, and triples will always result in a runner being on third base.

You’ll notice that runners on 1st and 2nd, 1st and 3rd, and having the bases loaded don’t come up at all on this chart. That’s because these are all power number results — in other words, every one of these results in a double or better. We’ll look at the singles in a future post.

I should also note that play result 3 with runners on second and third results in a run scoring double and the batter being thrown out at third base trying to stretch a triple. That’s the only power number in National Pastime that results in an out.

If you play a full National Pastime season replay, you still might never see a 3 come up with runners on second and third, by the way. That’s because play result number 3 is the second least common play result in National Pastime — behind result 2, which is almost always a triple:

By the way, if you’re curious, there were a total of 657 triples in the American League in 1930:

And there were 625 in the National League:

Triples were as common as home runs in the 1930 American League, which should really make your head spin. Times were certainly different. Home runs were a tad more common in the National League, thanks in large part to the slugging performance put on by the Chicago Cubs.

Of course, if Clifford Van Beek were actually using triple statistics for 1930 for his cards, we’d see a lot more of play result 2. This is more evidence that Clifford probably used a more limited data set than we like to imagine.

Other than that, honestly, there’s really not much of a pattern in those power number results. There is perhaps a little bit of evidence that Van Beek saw play result number 5 as the second most powerful number, behind 1: after all, 5 turns into a home run on 3 of the 8 on base situations. It’s also possible that a 3 was seen as more powerful than a 3, since the runner on first base doesn’t score when you roll a 6. Of course, Clifford gave out 251 of those 6s, but only 9 of those 3s — which is why most players likely won’t notice the difference.

One wonders what would have happened if Van Beek had separated base running from the play results. Perhaps he could have invented a game free from the cumbersome playing boards — something that might have felt more like basic Strat-O-Matic than APBA.

I think Van Beek got the idea of using different boards for each on base situation and having baserunner advancement dictated by the boards from the old Steele’s Inside Baseball game:

Unfortunately, I don’t know of any clear photos of the Steele boards, nor do I know of any transcription out there. Please let me know if you have a copy: I’d love to mess around with it and see if there are indeed any additional clear ties between that game and National Pastime.

Of course, you can read more about Steele’s Inside Baseball in this earlier post:

All in all, I think National Pastime is a far simpler game than we’ve given it credit for. It’s certainly more interesting and more playable than the earlier dice baseball games (including Steele’s game). However, I really don’t see much evidence that Van Beek’s cards were somehow more “realistic” than J. Richard Seitz’ original 1950 APBA set.