Pitcher Extra Base Hits On 66 In National Pastime

This is a pretty obscure topic, isn’t it? It’s also the natural outgrowth of our study of the old National Pastime board game.

Look: you can’t understand the history of APBA without understanding National Pastime. And you simply can’t understand National Pastime without digging in a little bit.

If you’ve forgotten (and I don’t blame you), we talked about 13s and 14s on National Pastime pitcher cards last time.

It’s time to look at one of those big anomalies: dice roll 66.

66s

66 has captured the heart of every APBA fan. There’s nothing quite like rolling a 66 in a clutch situation, watching a hopeless defeat turn into a sudden victory with an unlikely home run.

It’s pretty clear that dice roll 66 was the “best” dice roll in Clifford Van Beek’s game design. J. Richard Seitz adopted a very similar dice roll heirarchy for his game.

However, there’s something strange going on with dice roll 66 on National Pastime pitcher cards. Every single pitcher has either play result number 4, 5, or 6 on dice roll 66, regardless of his offensive performance.

Furthermore, no pitchers have a home run number. That includes those who hit home runs in real life.

We’ll get to specific players in a minute. Let’s look first at these play result numbers and see what they mean.

4, 5, and 6 in National Pastime

Remember this old Robert Henry post?

It comes from this article I wrote a few months back:

National Pastime Play Result Numbers

National Pastime Play Result Numbers Last time I talked about checking the play result numbers against the boards to get a better idea of how frequently each National Pastime on-base situation is likely to come up. It’s actually a little bit more complicated than that.

Henry is completely wrong. There are no “triple” or “double” power numbers in National Pastime.

Here’s how it works. Play result number 1 is always a home run. Numbers 2 through 6 are broken down as follows:

A 2 is almost always a triple. It’s a home run if you’ve got runners on first and second.

A 3 is a triple in 3 base situations, a double in 3 base situations, and a home run in the other 2.

A 4 is a home run in 2 base situations, a triple in 3 base situations, and a double in 3 base situations.

A 5 is a home run in 3 base situations, a triple in 2 base situations, and a double in 3 base situations.

A 6 is a home run in 1 base situation, a triple in 1 base situation, and a double in 6 base situations.

The closest you have to a pure “triple” number is play result 2. Play result 6 is the closest you have to a pure “double” number. Everything else is in between — and, in fact, both 2 and 6 will also give you different power hitting results.

In other words, we need to stop thinking about certain play result numbers being “triple” or “double” numbers in National Pastime. That’s just simply not how the game was created, and is mostly the product of reading backwards into National Pastime from an APBA perspective.

The Pitchers

Now that we’ve got that out of the way, we can focus on what the pitchers have at dice roll 66.

Most of them have a 6. In fact. 64 of the 80 pitchers have a 6 on 66.

6 pitchers have a 5 at 66. An additional 10 pitchers have a 4 at 66.

Is there a correlation between these numbers? Not really. Here’s a brief look at the chart:

Instead of writing out every double, triple, and home run, I grouped all such hits together as extra base hits (XBH). I did this in part to save time, and in part because none of the numbers involved are “pure” double, triple, or home run play result numbers.

A few things of note:

There is no real correlation between the number of extra base hits and the result. Clarence Mitchell had 1 extra base hit in 1930 — a double. He got a 4 on 66, while George Ernshaw, with 9 extra base hits (8 doubles and a triple), wound up with a 6.

Players who had 0 extra base hits still received an extra base hit number.

William Sherdel, who only hit one solidary double in 1930, wound up with a 5 on 66. Note, however, that Sherdel had 9 career home runs to that point — which brings up a cardmaking theory we’ll get to later.

Three Examples

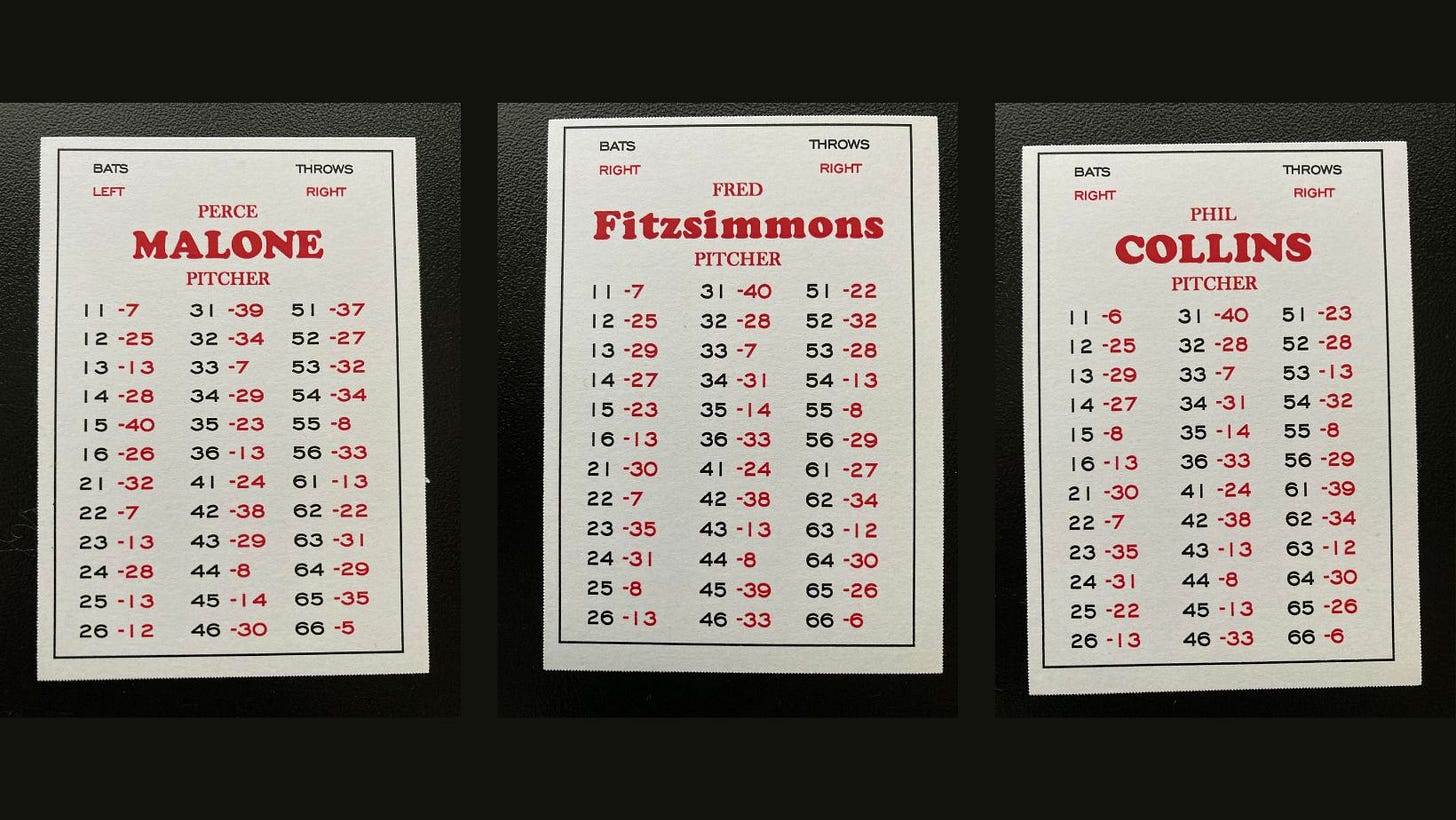

Let’s look briefly at 3 strange examples.

First is Pat Malone. Malone had an odd year at the plate in 1930, hitting 4 home runs and no other extra base hits.

Here’s Pat’s card:

He received a 5, which, as we’ve seen, is probably going to give him a few doubles and triples to go along with his occasional home run.

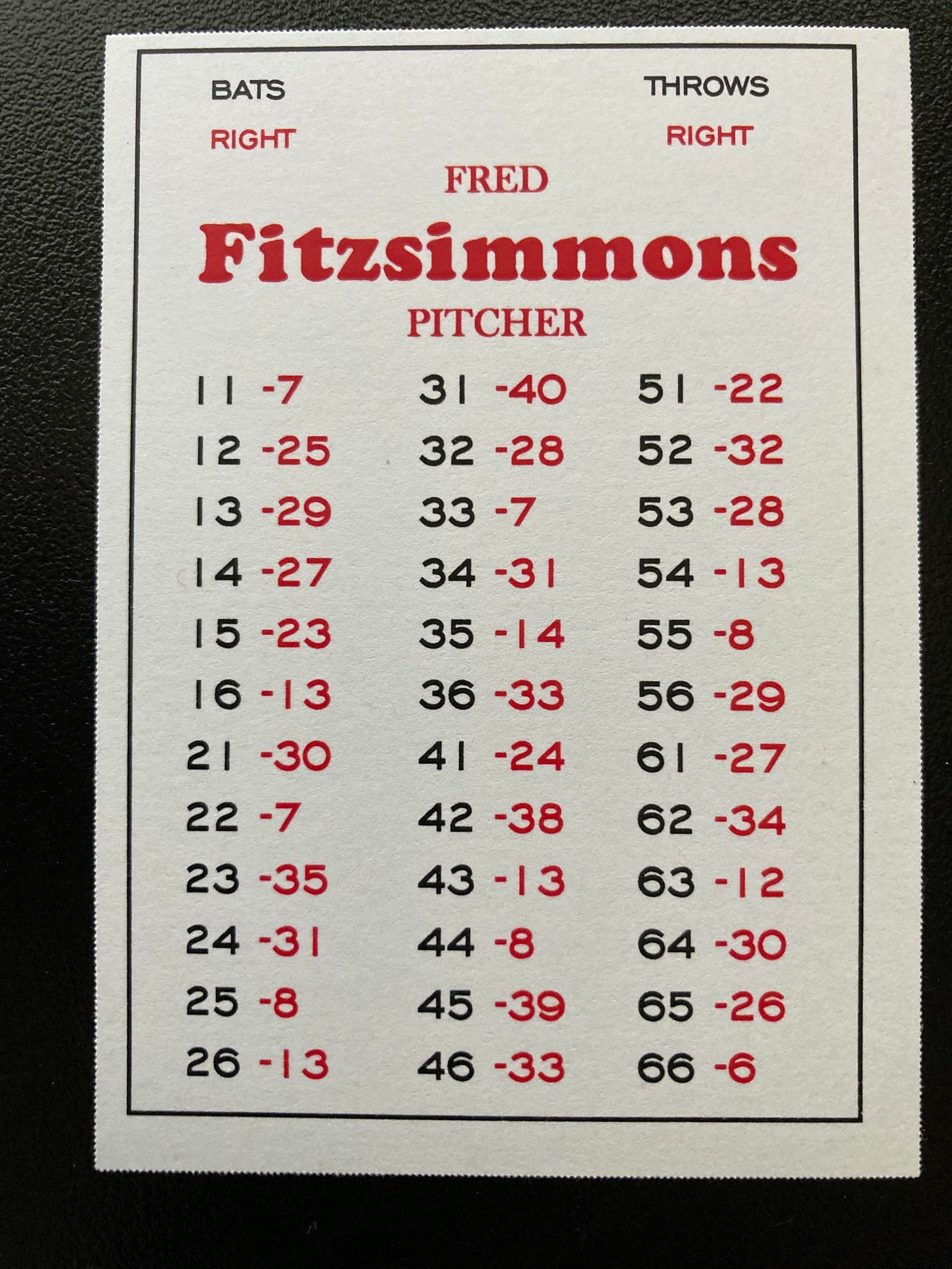

Up next is Freddie Fitzsimmons. Freddie had 3 doubles, 1 triple, and 2 home runs in 1930. Here’s his card:

Fitzsimmons received a 6 on 66, which, as we saw above, means he can only hit a triple with the bases loaded.

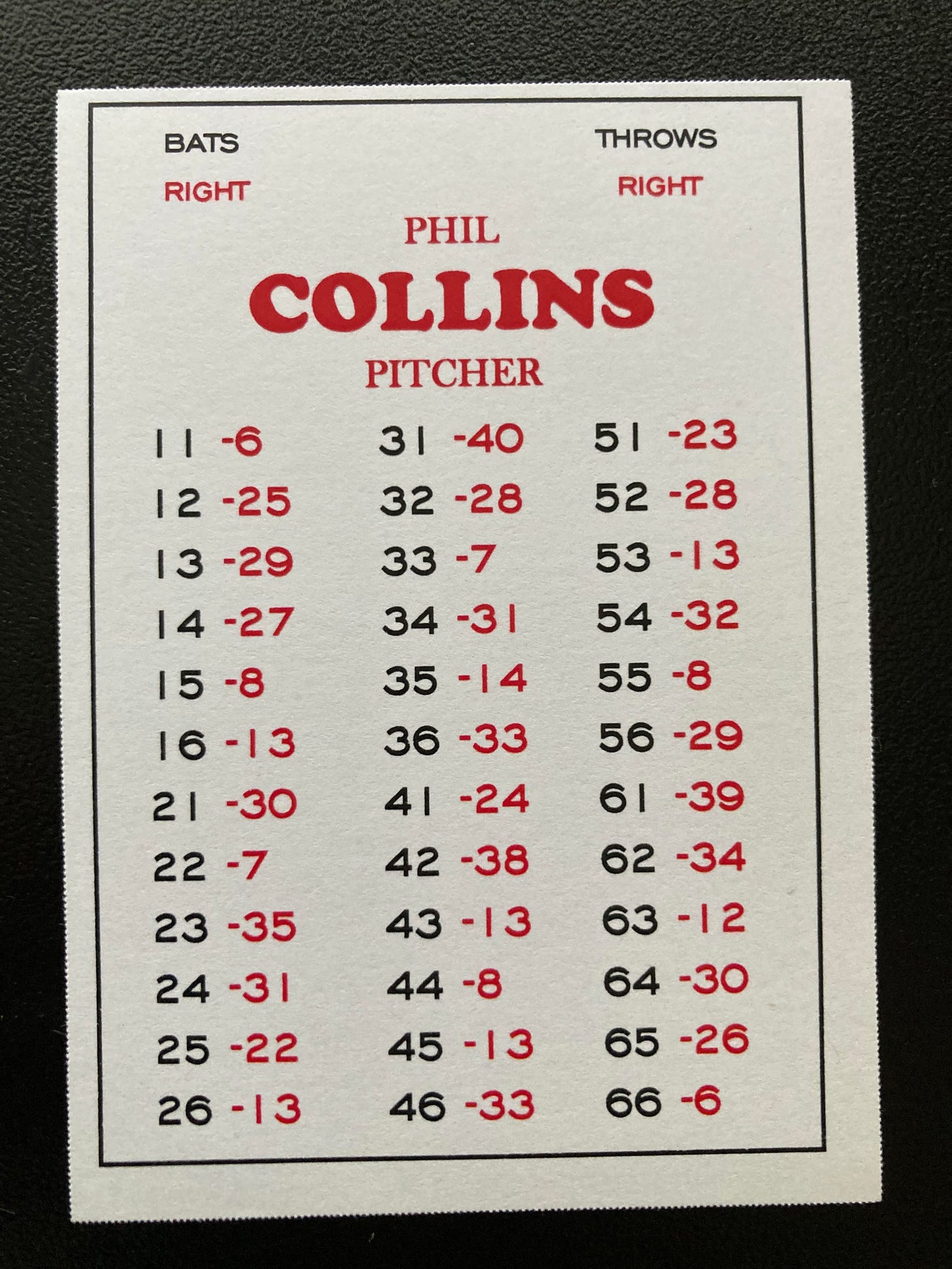

Finally, let’s look at Phil Collins:

Collins had 6 doubles and 3 home runs in 1930. He received two 6 play result numbers.

A few quick points:

Every pitcher received a 4, 5, or 6 on 66. Some pitchers received additional 4s, 5s, or 6s on other numbers. We’ll look into that next time.

It seems odd that Malone, who only had 4 home runs in 1930, received a 5, while Collins, who had 6 doubles and 3 home runs, received two 6s. Can anybody figure out the logic?

We’ll look into even more next time.