Pitching Stats In OOTP

There’s nothing wrong with ERA.

Okay - maybe there are a few things wrong with it. ERA can change based on the ballpark you’re playing in, for example, just like batting statistics. A bad pitcher in the Astrodome in the late 1960s will look good; a great pitcher in Coors Field in 1995 will look bad.

Strikeouts and walks are also a thing, of course. They represent without question something that pitchers have full control over.

But relying solely on raw statistics becomes difficult when you’re trying to find undervalued pitchers, or when you’re trying to figure out which guy to bring up from the minor leagues. Raw statistics also do a notoriously poor job of accounting for how much of a pitcher’s performance is likely due to the fielding behind him.

And that’s the reason why we have advanced statistics.

When people talk about pitching statistics in OOTP, there are three different statistics that constantly pop up: FIP, BABIP, and ERA+.

We’ll go through these one at a time, though I’ll tell you more about what the stats mean and how to use them than the technical details about how they work.

FIP, or Fielding Independent Pitching, is a measure of how effective a pitcher is when you only take into consideration stats that don’t rely on fielders. You’re looking at home runs allowed, strikeouts, hit batters, and walks — stuff that has nothing to do with the fielders behind the pitcher.

The idea here is to isolate the pitcher’s effectiveness from anything that could conceivably be because of the fielders behind him. This could show us cases in which good fielding makes pitchers look better than they really are.

Based on posts like this, it seems that the general rule of thumb is as follows:

If FIP is a lot lower than ERA, the pitcher was likely “unlucky.” In other words, the ball was probably hit to places where the fielders weren’t playing.

If ERA is lower than FIP, it might be an indication that the pitcher had good fielding behind him.

FIP is pretty closely related to BABIP, though they basically measure the opposite thing. We saw the other day that BABIP is all about the batting average hitters have when we only consider balls put in play. It tells us something about hitters — but it turns out that it likely tells us something more interesting about pitchers.

It turns out that BABIP for pitchers tends to regress to the mean. There are a ton of sources for this available online; this article is a pretty good starting point. In other words, if you’ve got a pitcher whose BABIP is a long way off from the league average, there’s a pretty good chance that his BABIP will be pulled closer to the league average the next year.

Let’s take a look at these in action.

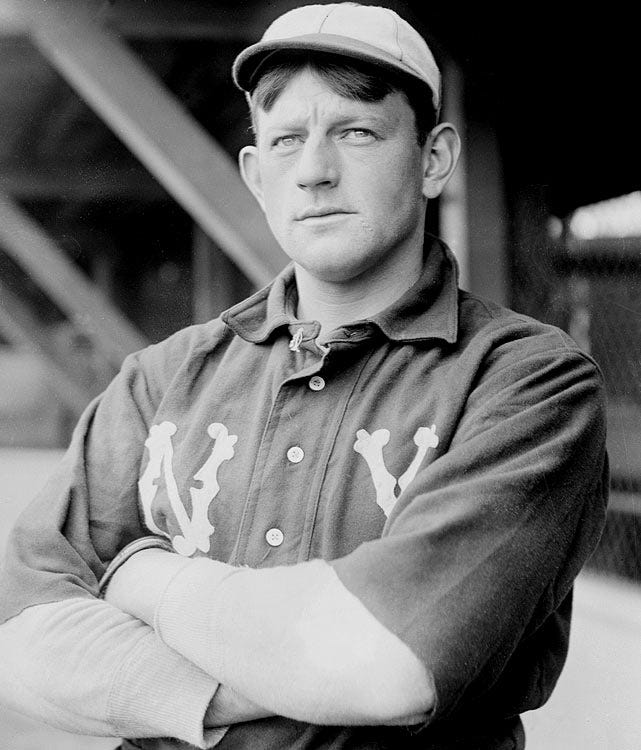

Most sabermetricans stay away from the deadball era, since crazy things happened back then. And so that’s precisely what we’re going to look at. More specifically, let’s look at Jack Chesbro’s famous 1904 season, the season where he won 41 games.

Chesbro went 41-12 in 1904, which is the sort of statistical fact that young baseball fans once knew, but that nobody seems to care about these days. He had an ERA of 1.82 in 454 2/3 innings pitched, which is pretty impressive, especially since his ERA didn’t even lead the league.

But we’re being sabermetricans now. We want to see what these other fancy stats tell us about Chesbro.

Jack’s FIP in 1904 was 2.11 — a bit above that 1.82 ERA. We’d expect from this that Chesbro had unusually good defense behind him — or perhaps he was pretty lucky.

Also, thanks to FanGraphs, we know that Chesbro allowed a BABIP of .243 in 1904. It just so happens that the American League BABIP average in 1904 was .275. That’s another sign that Chesbro might have been pretty lucky — and that we might expect his ERA to rise in the future.

And that’s exactly what happened. Chesbro went 19-15 with a 2.20 ERA in 1905, then 23-17 with a 2.96 ERA in 1906, 10-10 at 2.53 in 1907, and 14-20 with 2.93 in 1908. He was never even close to the pitcher he was in 1904.

Some of that might have been due to poor fielding. His FIP in 1906 was only 2.30; his FIP in 1907 was only 2.18.

However, the really interesting thing here is that Chesbro’s BABIP increased dramatically after 1904 — even though the American League BABIP stayed relatively constant. It jumped up to .269 in 1905, then a whopping .290 in 1906, down to .276 in 1907 and .277 in 1908, before finally ballooning up to .351 in 1909.

The league average BABIP is kind of like a magnet. Pitchers who are far below that total tend to be pulled back in. Those who are far above also get pulled back towards the center — if they manage to keep their jobs, that is.

That leaves us with ERA+, which is the easiest of the three metrics to understand. It’s basically a version of ERA that is adjusted for the ballpark you play in and the league you play in. It’s also normalized to the point where 100 is average, anything above 100 is good, and anything below 100 is not so good.

Unlike FIP and BABIP, however, ERA+ doesn’t necessarily tell us much about how the pitcher might do in the future. Chesbro had an ERA+ of 148 in 1904, which dipped to 132 in 1905 (still a good number), then down to 100 in 1906, 110 in 1907, and all the way down to 84 in 1908.

However, the nice thing about ERA+ is that it gives you some sort of context to the pitcher’s raw statistics. Instead of looking at Chesbro’s 1.82 ERA in 1904 and wondering if he pitched in an airport, we can look at the 148 ERA+ and figure that he was a star pitcher in the American League that season.

Let me know what you think in the comments!

I have this game but can not figure out how to do a retro replay. I bought it in a sale a couple of seasons ago. I can’t seem to find a video on how to setup and play an older season.