Revisiting National Pastime Power Numbers

About two weeks ago, I wrote that I thought Clifford Van Beek was likely just guessing on double and triple numbers:

I now think I was wrong.

After putting it off for several months, I finally sat down and inputted real life statistics into my massive National Pastime spreadsheet. I also devised a crude way to calculate the expected value of each dice roll.

Just like yesterday, we’re assuming that board situations in National Pastime will show up with the same frequency as real life. In other words, we’re assuming that each situation will come up at this frequency:

Bases empty — 55%

Runner on first — 20%

Runner on second — 8%

Runner on third — 3%

Runners on first and second — 7%

Runners on first and third — 3%

Runners on second and third — 2%

Bases loaded — 2%

This is based on numbers I reported here:

Now, as you know by now, play result numbers 2 through 6 might be a double, a triple, or a home run based on the on base situation. Since we know the boards and have base situation percentages to work with, we can calculate the value each of those numbers has for each outcome:

In other words, play result number 5 will be a home run 31% of the time, 2 will be a triple 93% of the time, and 6 will be a double 95% of the time — assuming, of couse, that the play situation frequencies we calculated are correct.

Now, we don’t know if those are correct or not. In fact, I’m quite confident that they aren’t the numbers that Clifford Van Beek actually used when he created National Pastime. For a while, I suspected that he might not have used any numbers.

But now I think he almost certainly did.

The expected number of doubles, triples, and home runs from the cards matches the real life totals of the players almost exactly.

We’re not talking about something that is minor or easy to stumble upon, either. We’re talking about a phenomenon that is pretty remarkable. But we’ll get to the significane in a minute.

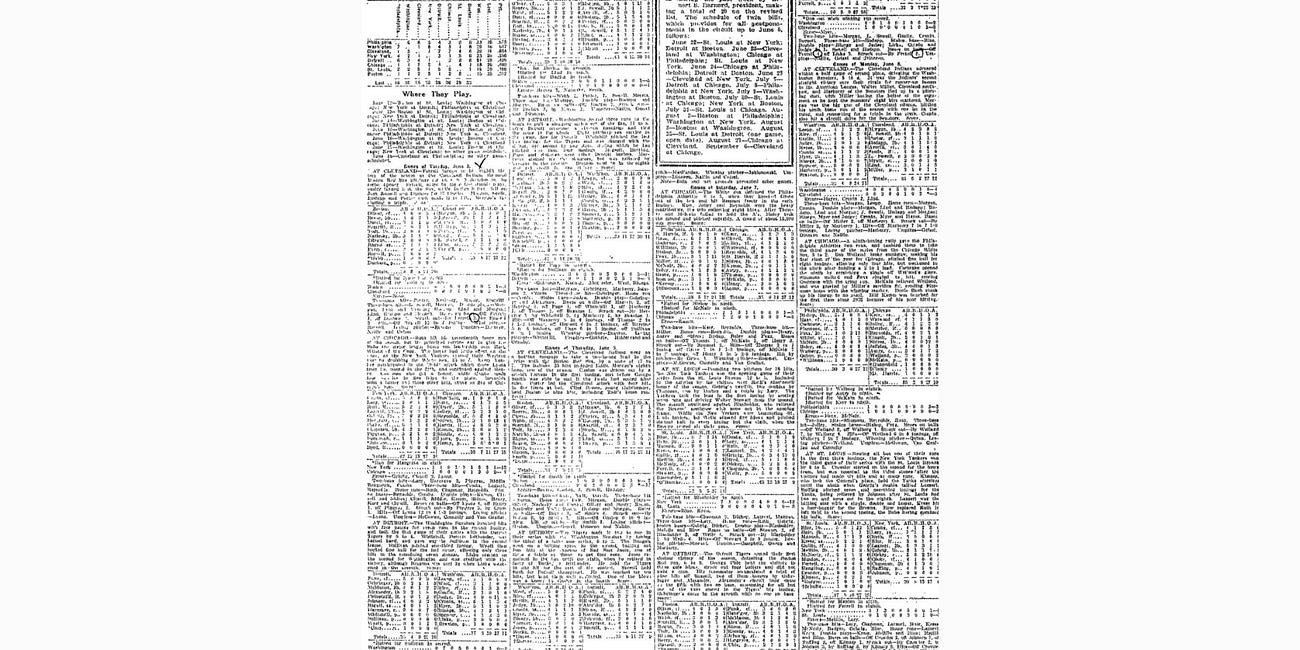

Let’s start off with expected home runs, which is what most people care about. Here are the top 37 home run hitters in the major leagues in 1930, organized by home runs hit in real life. The XHR column is the expected number of home runs from their National Pastime card, provided that they received exactly the same number of plate appearances they had in real life:

The only real outlier here is Babe Ruth, who received three 1s and two 4s on his card. I think we could excuse Van Beek for maybe hoping that Ruth would hit 60 home runs again.

But it’s not Ruth that I care about. It’s everybody else. As you can see, the vast majority of players are almost right on — and those that aren’t exactly right are extremely close.

I theorized yesterday that Van Beek may have had end of season totals of home runs for each player. However, I’m pretty sure he didn’t have the correct number of doubles. But look at what we get when we do the same thing for doubles:

See what I’m saying? The numbers are too good to be a coincidence — and are far too good to conclude that Van Beek was just making stuff up.

I’ve mentioned before, of course, that players who hit 0 doubles in 1930 will wind up with doubles in National Pastime, as you can see here:

That’s not very realistic, sure — but it seems like a footnote at this point. I doubt you’d care much if Waite Hoyt hit one or two doubles in your replay.

Now let’s look at triples — and triples is where I was sure I had Van Beek in a corner:

The expected triple numbers are indeed off — but they’re not really uniformly off. Some players are close, some will get more than they had in real life, and some will get less.

That’s incredible.

In fact, that has me suspicious that Van Beek might have actually compiled these statistics himself based on newspaper boxscores, or boxscores printed in The Sporting News. Though it would have been difficult, it is possible that Van Beek might have slowly collected statistics on graph paper or something similar as the 1930 season went on.

That’s the only way I can account for him having these statistics for 288 players. Newspaper accounts at the time simply didn’t print weekly or monthly running totals of doubles and triples. And these stats are way too close for this to be a coincidence.

By the way — this theory fits in with my theory that Van Beek kept track of actual lineups using 1930 boxscores as well. I wrote about that here:

Let me know what you think.