This post includes affiliate links. If you use these links to purchase something, this blog may earn a commission. Thank you.

Dynasties and Rosters

We’re going back to that book Baseball Dynasties for today’s post.

I previously wrote a review of the book here, and explained a bit about the domination index here.

Neyer and Epstein spend a bit of time talking about using multi-year spans to look for periods of franchise domination, which they call “dynasties.” Here’s an explanation from their introduction (apologies for the formatting):

This isn’t a bad idea, but there’s a problem here: you’re not necessarily dealing with the same team.

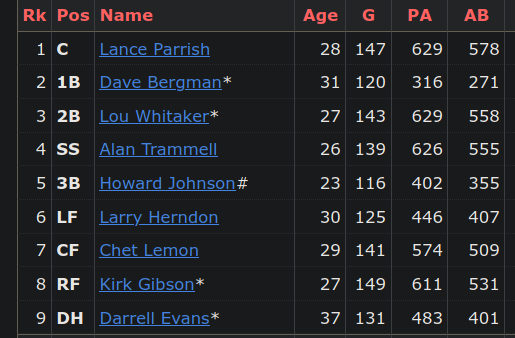

1984 Tigers

Let’s look at the 1984 Tigers as a quick example. We’ll focus on starting players at each position.

Here are the starting players for the 1984 Tigers per Baseball Reference:

We can argue that Barbaro Garbey should probably be listed at first base instead of Dave Bergman, but we’ll leave that argument for a later time.

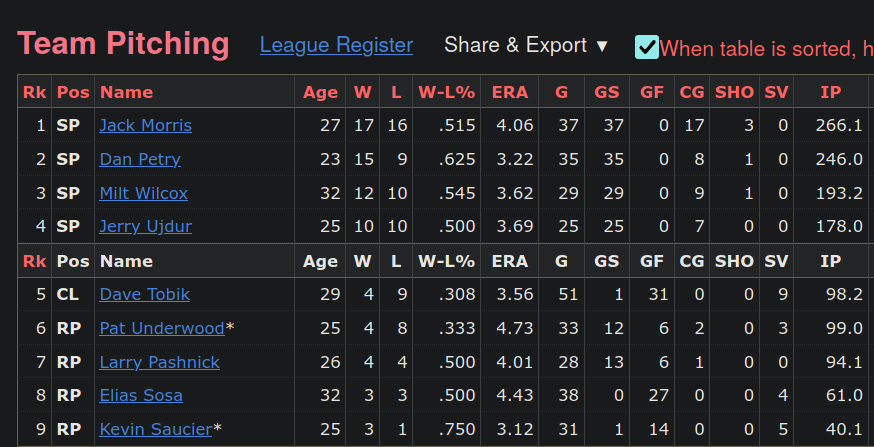

And here is that famous 1984 Tiger pitching staff:

Okay, now that we’ve established that, let’s take a look and see what the team looked like in 1982, starting with the lineup:

Right away, we can see some differences — some that are probably significant. Enos Cabell played at first base instead of Bergman; Tom Brookens played at third instead of HoJo, and Glenn Wilson played in the outfield instead of Kurt Gibson. The designated hitter was Mike Ivie, instead of Darrell Evans.

Sure, Gibson and Johnson were on the team in 1982 — but they weren’t regular players yet. And that’s the point. Why are we looping in the 1982 Tigers with the 1984 Tigers when the roster and makeup of the team was completely different? Why conclude that the 1984 Tigers weren’t great because a bunch of players who used to play for them weren’t all that great?

The problem isn’t quite as obvious with the pitching staff, but it’s there as well:

Morris, Petry, and Wilcox were all there, and all seemed to have somewhat similar seasons. But Jerry Ujdur was playing out the end of his big league career in Cleveland in 1984. Dave Tobik was out in Texas, having been replaced by Willie Hernandez, who we used to think of as a great closer.

Again, it’s a completely different team. Why punish the legacy of the 1984 team because of the problems of the 1982 team?

Let’s look quickly at the 1986 team, just for fun:

Darrell Evans actually played 47 games at 1B in 1984. In 1986, he put in 105 games (864 innings) at the first sack: a pretty hefty workload for a 39-year-old.

We know about Whitaker and Trammell. Darnell Coles was on Seattle in 1984, and seems to have been yet another attempt to fill the hole left by HoJo’s trade to the Mets after 1984. Was Walt Terrell really that good?

Herndon, Lemon, and Gibson were still there, of course. The veteran Grubb actually did have a part-time DH role with the Tigers in 1984 as well.

And here are the pitchers:

Morris was still there, of course. We just mentioned Terrell. Tanana came over from Texas in 1985. Eric King was a rookie in 1986.

Again, it seems kind of silly to cast aspersions at the 1984 Detroit Tigers because of poor performances by completely different players. Besides, if you directly compare the 1982 Tigers with the 1986 Tigers, you’ll feel like you’re looking at two completely different teams.

The Best Dynasties?

Here are the top 5-year Domination Index teams that Neyer and Epstein found:

Note that I haven’t done these calculations myself. Remember that we saw last time that some of their calculations appear to be a little bit off.

We’ll go through three of these teams: the 1935-39 Yankees, the 1969-73 Orioles, and the 1986-90 Mets. I’ll keep this short and simple.

1935-39 Yankees

For the sake of simplicity, I’ll use as spreadsheet from here on out. We’re not going to worry about stats; instead, we’ll just look at player names and move from there.

Here’s a direct comparison of the 1935 and 1939 New York Yankees rosters, listed by position per their Baseball Reference pages:

Now, we know that the 1935 Yankees finished just 3 games behind the Detroit Tigers, and that the 1939 Yankees were arguably the greatest team in baseball history.

Notice, though, the similarities and differences between these teams. Remember that this is the reserved list era: there was no free agency to speak of in the late 1930s.

We know about Gehrig’s disease. Even if we ignore him, though, there are other 3 significant roster changes among the 8 starting players. There were also 3 changes in the starting rotation (I simply limited both teams to 5 pitchers for the sake of simplicity). Johnny Murphy did finish out quite a few games both years, though he doesn’t really fit the modern definition of “closer.”

Of the 14 slots listed here, there are 7 changes. The teams are similar enough to still be the Yankees of the late 1930s, but are still remarkably different. Can we really call them part of the same “dynasty?”

1969-73 Orioles

We’ll just ignore the designated hitter, since it’s not fair to compare things across rule changes.

I was actually surprised in how much the Orioles changed from 1969 to 1973. I initially thought that this team would ruin my argument.

Davey Johnson wound up in Atlanta. Frank Robinson went to the Dodgers in 1972, and wound up in California for 1973. Tom Phoebus was no longer in the majors in 1973 — a surprise, since he was only 27 in 1969. The same goes for Jim Hardin, who was only 25 in 1969.

Eddie Watt was actually still on the Orioles, and pitched the exact same number of innings both years: 71.0. I guess that’s what happens when you oversimplify the argument.

My point stays the same, though. Even though both teams finished in first place, does the success of the 1973 Orioles really tell us anything about how good or bad the 1969 team was? In other words, does Bobby Grich’s good play at second base in 1973 really contribute in a meaningful way to the 1969 team, which Grich never played for?

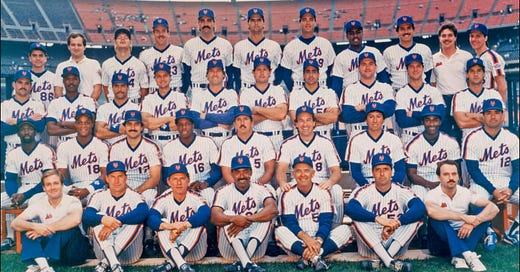

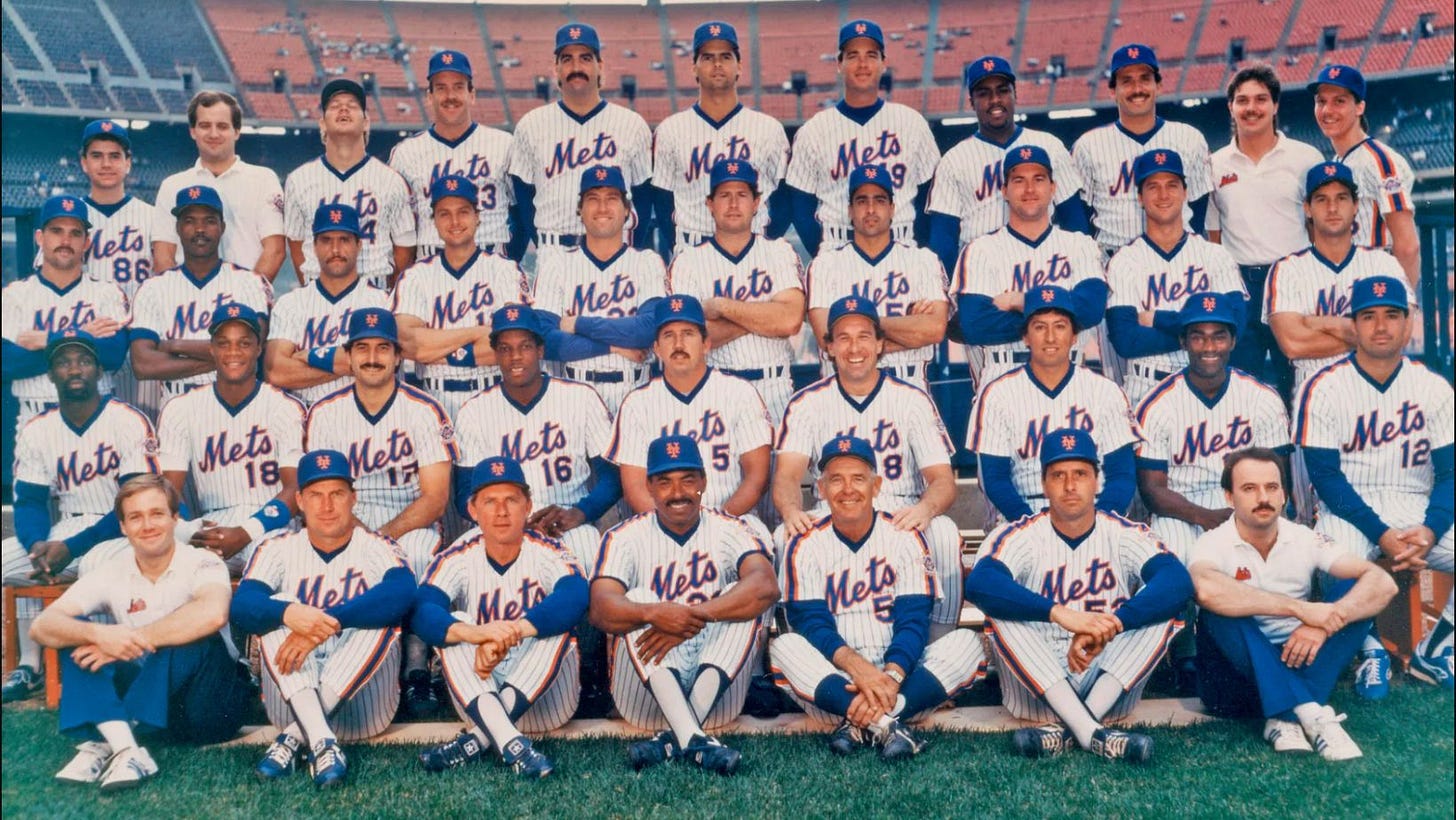

1986-90 Mets

This “dynasty” is the reason why I decided to write this blog post. These teams are simply not the same.

I can’t necessarily blame the Mets for not wanting to resign the 36-year-old free agent Gary Carter in 1990. Hernandez, also at age 36, wound up signing for Cleveland, also as a free agent.

Wally Backman was traded to the Twins for, well, nobody. We could make an argument that Elster should count as a shortstop for the 1986 Mets, since he spent some time playing at the bag that year. For his part, Santana surfaced with Cleveland briefly in 1990 for his last change in the majors.

Ray Knight retired by 1990. Most Mets fans will argue that Foster shouldn’t even be listed on that 1986 Mets team, and we all know what happened in Cincinnati. Even if we listed Kevin Mitchell there, though, we’d have to mention that he went to San Francisco a few years later. Danny Heep, the other left fielder, went to the Dodgers in 1987.

Dykstra split time with Mookie Wilson in center field in 1986, in an experiment that went south quick. Both Wilson and Dkystra wanted the starting spot, and rotating the two only made both unhappy. Fan favorite Mookie wound up going to Toronto in 1989, and, of course, Nails went to the Phillies.

Strawberry and Gooden were constants, though we all know about their drug problems. Darling and Fernandez were also on both teams. Ojeda was actually with the Mets in 1990, but pitched only 118 innings, mostly in relief. That’s understandable after Viola came over in that blockbuster 1989 trade, which is how Aguilera wound up with the Twins.

Generation K fizzled out, as we all know. I’d argue that replacing Gary Carter with Mackey Sasser probably had something to do with the Mets’ pitching woes in the early 1990s. The Mets went from being a team filled with young and exciting stars to an awful team of overpriced and entitled free agents, culminating in the awful 1993 Mets.

There is absolutely no reason to talk about the 1990 Mets in the same sentence as the 1986 Mets. They are two completely different teams — teams on completely different trajectories. The 1986 Mets looked like they’d be the next 1939 Yankees. The 1990 Mets, on the other hand, looked a lot more like the LOLMETS that would haunt Flushing.

Transactions

The key here, as you’ve probably guessed, is transactions.

What exactly are we trying to measure when we look at great team performances across years? No two teams are ever going to be the same. Players get injured, guys feel upset and ask for trades, players retire, young kids with great talent come up and beat out older men for starting spots, and on and on it goes.

Personally, I prefer to focus only on single season team performances when we talk about great teams. These multi-year measurements tend to ignore the interesting stuff and paint everything with a broad brush.

We’ll keep that in mind as we continue to talk about the greatest teams of all time in future posts.